by Dan O'Connor

(http://mises.org/story/3766)

[An MP3 audio file of this article, read by Floy Lilley, is available for download.]

"How selfish so ever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it."

"How selfish so ever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it."One of the few places in the world not yet plagued by government intervention is the internet. Although some governments in certain parts of the world have infiltrated the activities of the internet to varying degrees, it remains the closest thing to a purely free economy that we can identify in the modern world.

On the internet, the beautiful aspects of human nature manifest themselves, and we see individuals and companies maximizing their talents and resources for reasons of profit, pleasure, altruism, and mere progress in itself. Given that the government neither inhibits the activities of the internet nor props up or favors any particular actors or individuals, perhaps we are witnessing the closest thing to a free market that man has ever witnessed.

Although many consider the America of the 19th century to be the closest thing to a purely free market, in fact, congressmen constantly acted in favor of certain individuals, leading in some cases to monopolistic advantages. Ironically, at the end of the century the government intervened in an attempt to break up monopolies.

So here we are in a worldwide web that connects people from all parts of the world, allowing them to exchange whatever they want with one another. It is the essence of a free market: voluntary exchange. There is no use of force or coercion on the internet. No higher authority effectively controls or dictates the way that we spend our time online or the activities that we partake in. Although some legal obstacles inhibit people from accessing certain sites and materials, given the lack of regulation or enforcement by a higher authority, users are easily able to circumvent these restrictions and achieve the things that they want.

As it evolves, we begin to witness the endless potential that exists within the internet and the unquantifiable benefits it provides to society. Although the internet currently represents freedom from both a civil and a social perspective, I shall examine it from an economic perspective.

Arguably, the human race has seen more progress and innovation through the use of the internet in the past 20 years than through the use of any innovation known in the history of mankind. As we reflect back over the last 20 years, we see thousands of amazing success stories. We see entrepreneurs from all different economic backgrounds and classes making full use of their skills, ideas, and passions. We read about success stories such as Facebook and Google, where very young people have been able to generate massive wealth while providing a cheap, convenient, and valuable new tool for everyone across the globe to enjoy. This is the beauty of a system free from government intervention.

In fact, it's such a free market that government doesn't even effectively enforce intellectual property and copyright protection. And what is the result? We see entrepreneurs from other countries imitating successful online programs with very little detriment to the originators. In fact, Chinese entrepreneurs have created very similar programs to both Google and Facebook. As a result, all of these companies have been able to generate profits while their users still enjoy the programs at no cost.

"Very young people have been able to generate massive wealth while providing a cheap, convenient, and valuable new tool for everyone across the globe to enjoy."In turn, their Chinese competitors bring increased competition to both Google and Facebook, creating incentives for them to improve their own products and continue to innovate. This example closely resembles capitalist Americans emulating European technology in the 19th century or Japanese entrepreneurs emulating Western technology during the process of their development.

Do patent protection laws truly promote greater and faster innovation? Some companies and individuals are able to avert these government-imposed rigidities online. And the success of this less-inhibited marketplace demonstrates the lack of need for patent protection laws.

If patent-protection laws, taxes, and legal-tender laws were completely eliminated from the internet, we would then see a purely free market. Although this is not foreseeable given the world's current political system, we can still continue to enjoy the advantages of this relatively unfettered aspect of modern society.

Technological advancements benefit society for many obvious reasons. In an unfettered marketplace, innovation reduces costs for businesses and hence prices for consumers. For example, in the past, some families spent several hundred dollars every few years just to update their encyclopedia set, even though all of the content in these encyclopedias was publicly accessible; the encyclopedia companies merely compiled the information into a more concise format.

Although these companies provided a very valuable product to society, there is now a decreased need for physical encyclopedias due to the increase of information available on the internet. Let us hope the Obama administration does not attempt to "bailout" Britannica anytime soon.

We begin to see so many things being offered on the internet not only for very cheap prices, but for free. Information that used to cost individuals and companies exorbitant fees can now be found on the internet freely, thus allowing individuals and companies to spend that money elsewhere, improving their own operations.

Before the internet took off in the 1990s, businesses across the United States spent billions of dollars every year on information. Nowadays, companies save millions of dollars per year on research, data, and inventory, which can now be spent on other areas of the business, such as rewarding employees with higher bonuses or purchasing new facilities and advanced equipment. The economy as a whole is operating more efficiently, as overall costs and expenditures have gone down.

"Let us hope the Obama administration does not attempt to "bailout" Britannica anytime soon."Often the most neglected benefit of technology for society is decreased prices. During and after the time of the Industrial Revolution in the United States, we witnessed a myriad of price reductions across most industries. As prices dropped and the cost of living decreased, individuals and entrepreneurs were encouraged to identify other niches throughout the market and introduce new technologies.

Unfortunately, much of modern society has a hard time grasping the benefit of price decreases, while central banks throughout the world continue to print money, which leads to price increases.

In modern times, we can purchase almost any sort of product via the internet and can access almost any information that we desire. When we consider the vast number of people and companies throughout society that earn profits by merely providing information, we can only imagine the enormous costs that can be saved as a result of more accessible and cheaper (often free) information now available to all of society online. What is even more encouraging is that we see the providers of this information doing so for reasons other than profit — a reflection of man's pursuit of passion and his innate sense of compassion.

Unfortunately, as has always been the case, the internet and its infinite value to society is threatened by a ubiquitous force: government. As we've seen throughout history, when companies become threatened by competitors, they do whatever is possible to prevent or squash competition — often through the use of government force.

In the 1930s, unions used various means for lobbying in DC in an attempt to introduce a minimum wage law, which ultimately passed. Smaller companies who could not afford to pay these increased wages were soon forced out of business.

Sure enough, various actors in DC are now lobbying to regulate the internet. In April 2009, AP began to publicize a widespread attack on Google — arguably the most successful company and widely enjoyed technology of the past 10 years. As more and more information-providing companies see their revenues dwindle as a result of better and more convenient information being provided by competitors on the internet, we can be certain that a greater number of companies will congregate in DC to propose greater regulation.

Let us hope our government is stern enough to defend the Constitution as it was written with the intent of dealing with this type of dilemma. The first amendment, freedom of the press, was most strongly emphasized by Thomas Jefferson. He stated, "Where the press is free and every man able to read, all is safe."

The internet is a model of the free market. It represents all of the aspects of capitalism that we cannot witness in our current offline world due to the high level of government intervention that pervades our society. Online, we see widespread competition, low barriers to entry, voluntary exchange, rapid technological advancements, decreased prices, and a flowering of creativity.

Dan O'Connor has lived in Asia since early 2004. Send him mail. See Dan O'Connor's article archives.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Witness the Freest Economy: the Internet

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife

Listen to Podcast

From the depths of history, to the classroom, to the stage, how do we understand the enduring influence of the story of Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl? Francine Prose, adoring fan and author of Reading Like a Writer will join us to discuss the book, the life, and the afterlife.

Guest

- Francine Prose, author of Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife

Friday, October 09, 2009

School Sucks Podcasts: Episode 1 - Introduction to School Sucks Podcast

(http://schoolsucks.podomatic.com/)Critical Thinking Question:

How many things that are good for you, that you will benefit from, need to be imposed on you...with force?

Introduction:

Explanation of title, "School Sucks" and subtitle "The END of Public Education"

Who I am, what I'm doing and why.

This is not a show about public school reform, because that would suck nearly as much as school.

Topic:

The problem with the "business?" of public education. And it's a big one. (An evaluation of the logic and ethics of the American public education system)

Bumper music: "Troublemaker" by Weezer

http://www.youtube.com/user/weezer

Look Closer:

"The Non-Aggression Axiom of Libertarianism"

by Walter Block

http://www.lewrockwell.com/block/block26.html

"The Argument From Morality (Or, how we will win…)"

by Stefan Molyneux

http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig6/molyneux7.html

"For A New Liberty" (Chapter 7: Education)

by Murray Rothbard

http://mises.org/rothbard/newlibertywhole.asp#p119

The Protestant 'Work-Shy' Ethic?

(http://bhascience.blogspot.com/2009/10/protestant-work-shy-ethic.html)At the start of the 20th Century, the sociologist Max Weber came up with a famous theory to explain why Northern Europe and North America were so prosperous: the Protestant Work Ethic.

Basically, the idea was that a unique feature of Protestant Christianity is its emphasis on work as a duty to God. While other religions asked people to do things that were laborious and time consuming, only Protestantism (so the theory went) channelled that religious duty into productive work.

It's important to take some time out here to understand what's meant by 'work ethic'. It certainly isn't simply productivity. The richest, most productive countries actually have the lowest work ethic.

And a lack of 'work ethic' doesn't mean you're lazy or driven only by financial reward. In fact, educated people have a lower 'work ethic' than uneducated people. Clearly educated people aren't lazy - they work hard to get their qualifications and don't get paid to do it.

So 'work ethic' is actually about working for no clear purpose - it's work for work's sake.

Well, in the 100 years since there's been a lot of debate and no clear conclusion about whether Weber was right. But, in theory, it seems plausible. According to economists, people only do work if they are going to get some kind of reward. If you can convince them them that their reward will be 'magical' (some kind of spiritual reward in this life or the next) then you won't have to pay them as much.

In modern economic terms, a Protestant would gain extra 'utility' from doing work, and so they would have additional motivation to work harder.

But even if the idea did hold in the past, does it still work in the modern world? And if it does, how does it work in practice? A new paper by Hans Geser has taken a look.

He scrutinized data from the Christians in the World Values Survey and found that, as far as work ethic goes, Protestantism probably isn't very much different from Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity.

But he did find some interesting relationships with religion in general. Basically, people with stronger religious faith have a stronger work ethic. But other factors of religion - whether people took Church teaching seriously, whether they went to Church, or whether they prayed - seemed to have little or no effect.

There was a surprise, however. Belief in an afterlife actually had a negative effect on work ethic.

The effect of religion was small. Overall, only around 5% of the variation between people in work ethic is explained by religion. But Geser's analysis suggests that it's not due to religious teachings. And the promise of a reward in heaven actually has a negative effect.

Which suggests that the reason religious people have a higher work ethic is that they expect to get a reward for it in this life, rather than the next.

One last thing. The effect of religion, which is small even in poor countries, disappears in rich countries. That's not because the effects at an individual level get less. What happens is that the 'national average' intensity of religious faith has a cultural effect - increasing the work ethic of believers and non-believers.

As countries get richer, their culture shifts from a religious to a secular one. And with that, the idea of working for the sake of work becomes marginalised. In rich countries, people work because they see a reason to do the work._______________________________________________________________________________________

Hans Geser (2009). Work Values and Christian Religiosity: An Ambiguous Multidimensional Relationship Journal of Religion and Society, 11 (24)

Small Town, Big Government

by Bob Gough(http://biggovernment.com/2009/10/02/small-town-big-government/)

[ED: Big Government isn't just in Washington, DC. In this story, local Republicans and Democrats tag-team to put out of business a local charity providing safe rides home from local bars. Often, the fight against Big Government begins at home. This installment comes from the editor of the great local news site, Quincy News.Org]

Jonathon Schonekase can’t seem to escape his past.

He changed his name hoping people would forget about his setting fire to an abandoned school when he was a juvenile. He then went to prison as an adult, where he lost his eye in a fight.

Jonathon said the loss of a friend in a drunk driving accident gave him the idea to start a service where, maybe, he could give people an option to avoid drinking and driving.

Jonathon started “Courtesy Rides” on New Year’s 2008. He posted his number in bars, people called him and he picked them up. Didn’t cost them a thing. If they wanted to leave a tip, so be it.

Now more than a year and a half after starting the service, the town where he started it has decided Jonathon needs to be regulated.

The City Council of Quincy, Illinois (pop. 40,000 and change) passed an ordinance by an 8-5 vote to tweak the taxicab ordinance in the city code to classify his volunteer service as a “for hire” business if he accepts donations.

Jonathon became a victim of his own success. He did stray from the original mission of picking up people from bars when he gave rides to other places, including the Quincy Airport and when he added more vehicles and volunteer drivers. This drew the attention of the local cab company and shuttle services.

All of the charity he provided is now government regulated.

The simple answer should be for Jonathon to apply to become a taxi. But the city taxi licensing process has a “good citizen” provision and his conviction probably stands in the way.

But the irony is Quincy’s Mayor, John Spring, has talked publicly about the perils of drinking and driving. During his latest mayoral campaign, he even offered to pick up some young adults from the bars if they needed him.

This group of young professionals, YP Quincy, made the lack of local late night cab service in Quincy a cause celeb for a moment. This group, which has been lauded by local bureaucrats and the mainstream media for its formation, was absent during the “Courtesy Rides” debate, which lasted for about a month.

But a man who was making a difference, a man who was keeping hundreds of drunks out from behind the wheel each weekend, was told red tape was more important than saving lives.

A newly-elected alderman, Republican Dan Brink, was decided to take up this issue and ask the city’s legal and police department to consider amending the city’s code. Brink, who previously worked as a probation officer, was uncomfortable with Jonathon’s past, although he said the main reason he was doing this was to determine if he was a business.

Jonathon started “Courtesy Rides” because the cab company wouldn’t run pick up anyone after 1 a.m., which is when the taverns close, and people who went to the late night clubs were certainly out of luck as they are open for another two hours on weekends.

City Attorney Tony Cameron said when “Courtesy Rides” was one man and one car, it was his opinion in February it wasn’t a ‘for hire’ business. But Cameron also said that with more advertising and adding a van and a bus, “Courtesy Rides” comes “perilously close to a smell test as for hire.”

Quincy Police Chief Rob Copley also said the addition of more vehicles and making shuttle runs besides those late-hour bar calls changed things.

“I don’t think we’d be standing here if (Schoenakase’s) mission hadn’t changed,” Copley said.

But his ingenuity, his providing a service to those in need, was met with resistance. A Democratic alderman, Steve Duesterhaus, said “Courtesy Rides” needed to be regulated for “public safety” reasons with the licensing of his vehicles and background checks for volunteer drivers. The irony is, the regulation of this enterprise causes an even greater harm.

Did the city ask the lone cab company or the other shuttle services which it licenses to step up? Were they told to stay open to handle the weekend rush of people leaving the bars and instead of fumbling for their keys they fumble for their cell phones and call someone for a ride? No. Not a word.

The Quincy Police Department even conducted stings against “Courtesy Rides” to make sure he was indeed a voluntary service. QPD didn’t find any time where Jonathon or one of his volunteers asked for payment.

The need to regulate outweighing the city’s public safety. Bureaucracy in action.

Now some local conspiracy theorists will say that is because the city likes the revenues it gets from DUI’s. Copley takes great offense to this theory. He says he doesn’t want “drunks” on the streets.

Another disturbing result of this action is that the law now casts a wide net over other enterprises, including some courier services. What is disturbing is city officials say they will not go after them. They will only go after the “renegade cab companies”. Spot zoning for law enforcement.

Jonathon and his young attorney, Ryan Schnack, plowed into the bureaucracy head-on. The new ordinance proposed by the city’s attorney, Andrew Staff, took an overbroad stance on the legal term “consideration”. They claim that Jonathon’s service will now fall under their definition of “for hire” and thusly after the vote be enforceable to fines of an ordinance violation or attempt to prove his “good character” and become a taxi service and regulated under the City and State’s Taxi statutes.

On September 21st , during the ordinance’s second reading, the agenda heated up to force the vote on Jonathon’s fate. During this debate, the City hung its hat on the newly defined and refined city ordinance and ignored impassioned pleas to allow Jonathon to continue to operate.

One woman, Amy Zornes, lost her teenage daughter in a double-fatal alcohol-related crash just outside Quincy in April. She spoke from the heart about how she wished her daughter had called Jonathon.

“Nobody wants to be in my position,” Zornes said. “But kids won’t call their parents because they don’t want to get in trouble. They can call Jonathon.”

When Zornes finished her impassioned plea before the City Council, complete with blown up pictures of her daughter’s crash scene, she was publicly brushed off by the mayor.

“You really didn’t address the ordinance change,” was all Mayor Spring said.

The lead of the local Mothers Against Drunk Drivers chapter then said she wished every town had a “Courtesy Rides”. She wasn’t treated quite as rudely. Maybe because she was in a wheelchair.

The young attorney was asked by the City Council to provide documentation of conversations he had with various state agencies who Schnack claimed had told him they didn’t see a problem with “Courtesy Rides”. But the state agencies wouldn’t provide Schnack with any documentation, probably because no bureaucrat in Springfield wanted to stick their neck out for this.

Schnack asked Staff, the city’s attorney, to join in on a conference call with one of the state agencies to discuss the matter and Staff told Schnack he “didn’t have time to mess with” the matter.

Jonathon also didn’t provide documentation of proper insurance to the City Council. He said he went through GEICO and didn’t have a local agent who could appear with him at the Council meeting. I guess the gecko or the cavemen wouldn’t do.

So Quincy, Illinois has an ordinance changed that could put more drunk drivers on the street and expands the tentacles of government. This ordinance is now so broad that a person who takes money for carpooling kids to school on a regular basis could be breaking the law.

One of Quincy’s quirky qualities is that “Main Street” is spelled “Maine Street” as several streets in the center of town bear the names of states. Quincy’s city hall is located on Maine Street and while the street name is unique, what is happening in its city hall is all too common.

A man finds a niche. He provides a service. He is succeeding. He has come a long way from prison and his past.

Or so he thought.

The big government crowd will tell you this is a case where regulation is needed. But this is a classic example of government overreach. It’s the nanny state in full effect.

If a Quincyan doesn’t think Jonathon is safe, if they don’t like his record or his ride, they don’t have to call him.

But now it doesn’t look like they’ll have that option. Let’s hope they have someone else’s number handy.

The mayor’s office is 217-228-4545. After all, he offered.

The Conscience of a Capitalist

By STEPHEN MOORE

(http://online.wsj.com/articl/SB10001424052748704471504574447114058870676.html)The Whole Foods founder talks about his Journal health-care op-ed that spawned a boycott, how he deals with unions, and why he thinks CEOs are overpaid.

I honestly don't know why the article became such a lightning rod," says John Mackey, CEO and founder of Whole Foods Market Inc., as he tries to explain the firestorm caused by his August op-ed on these pages opposing government-run health care. "I think a lot of people who got angry haven't read what I actually wrote. There was a lot of emotional reaction—fear and anger. I just wanted to get people to think about whether there was a better way to reform the system."Mr. Mackey has flown into Washington, D.C., for a board meeting of the Global Animal Partnership, a group that advocates for the humane treatment of animals. There was no private jet: He arrived on Southwest Airlines from Austin, Texas, and he bought the "Wanna Getaway" bottom basement fare. "I barely got the last aisle seat," he says. While in town he stays in the bedroom of his regional president, who lives in Maryland.

For the 12th straight year, Mr. Mackey's company has been praised as one of the "100 Best Companies to Work For" by Fortune Magazine. Whole Foods sells healthy food, practices "socially responsible trade," and prides itself on promoting foods that are grown to support "biodiversity and healthy soils." Mr. Mackey donates 5% of company profits to charity and has been one of America's loudest critics of runaway compensation on Wall Street. And he pays himself $1 a year. He would seem to be a model corporate citizen.

Yet his now famous op-ed incited a boycott of Whole Foods by some of his left-wing customers. His piece advised that "the last thing our country needs is a massive new health-care entitlement that will create hundreds of billions of dollars of new unfunded deficits and move us closer to a complete government takeover of our health-care system." Free-market groups retaliated with a "buy-cott," encouraging people to purchase more groceries at Whole Foods.

Why did he write the piece in the first place?

"President Obama called for constructive suggestions for health-care reform," he explains. "I took him at his word." Mr. Mackey continues: "It just seems to me there are some fundamental reforms that we've adopted at Whole Foods that would make health care much more affordable for the uninsured."

What Mr. Mackey is proposing is more or less what he has already implemented at his company—a plan that would allow more health savings accounts (HSAs), more low-premium, high-deductible plans, more incentives for wellness, and medical malpractice reform. None of these initiatives are in any of the Democratic bills winding their way through Congress. In fact, the Democrats want to kill HSAs and high-deductible plans and mandate coverage options that would inflate health insurance costs.

The Whole Foods health-care story has been largely ignored by proponents of a government-run system. But it could be a template for those in Washington who want to drive down costs and insure the uninsured.

Mr. Mackey says that combining "our high deductible plan (patients pay for the first $2,500 of medical expenses) with personal wellness accounts or health savings accounts works extremely well for us." He estimates the plan's premiums plus other costs at $2,100 per employee, and about $7,000 for a family. This is about half what other companies typically pay. "And," he is quick to add, "we do cover pre-existing conditions after one year of service."

Whole Foods also puts several hundred dollars into a health savings account for each worker.This money can be used to cover routine medical expenses, like drug purchases or antismoking programs. If that money is not used in a year, the workers can save the money to pay for expenses in later years.

This type of plan does not excite proponents of a single-payer system, who think that individuals can't make wise health-care choices, and that this type of system is "antiwellness" because it discourages spending on preventive care.

Mr. Mackey scoffs at that idea: "The assumption behind that is that people don't care about their own health, and that somebody else has to—a nanny or somebody—has to take care of me because people are too stupid to make these decisions themselves. That's not been our experience. We find our team members [employees], not surprisingly, seem to care a whole lot about their health."

Not surprisingly, Mr. Mackey is a fanatic about healthy eating. "A healthy diet is a solution to many of our health-care problems. It's the most important solution. How much sugar do you think Americans consume?" he asks. I shrug and he rattles off the statistics: "Every man, woman and child consumes, on average, 43 teaspoons of sugar a day. In 13 days that adds up to a five-pound bag of sugar."

"We can spend all the money we want on bypass surgeries, chemotherapy and diabetes, but . . . two-thirds [of Americans] are overweight, one-third are obese." He's on a roll: "And it's not that they have to shop at a Whole Foods Market. But people need to eat whole food plant foods, primarily . . . whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds. That diet supports our lives. We ought to live to be 90 or 100 without getting any diseases."

Healthy eating, curbing the obesity epidemic—it's hard to find much of anything Mr. Mackey says that's controversial. But the health-care reform lobby continues to attack Whole Foods as if he were an apostate.

In response to the hullabaloo, Mr. Mackey has been understandably defensive. In early September, he wrote about the op-ed on his blog: "I gave my personal opinions. Whole Foods has no official position on the issue." So I ask him, does he regret writing the article? "I regret the controversy that it caused for Whole Foods, but I don't regret writing it, because I think what I said is true and it needed to be said. I wasn't seeing anyone else saying it."

Then he adds, half-jokingly: "I've written one op-ed piece in 31 years. It might be 31 more before I write another one."

I ask if he thinks the attacks were instigated by unions. While many other grocery chains are unionized, Whole Foods is not. "Well, the unions have had an adversarial relationship with us," he replies. "I don't think all the protests are strictly union-based, but I do think the unions have contributed to that. I think they've piled on and in some cases are orchestrating some of it." He says he can't divulge private information about whether the boycott hurt sales, but the stock hasn't taken any hit.

"I sometimes think that unions don't understand that we live in a free society and people have the right to not select union representation if they don't want it. I oftentimes hear things like 'Whole Foods is preventing people from unionizing,' which is a lie. That's illegal. We can't prevent anyone from unionizing," Mr. Mackey says.

So why aren't they choosing it? "Because it's not in their best interest," he insists. "We have better benefits and higher pay" than Whole Foods' unionized competitors. "We wish the unions would respect people's right to not have a union." Do they keep agitating? "Yeah, they do."

John Mackey is unlike any other Fortune 500 CEO I have met. He's got ruffled, curly hair, is thin and amazingly fit. He recently completed a three-week hike on the Appalachian Trail. He dresses casually, and his demeanor is almost always laid back. But his close friends say, don't let that fool you. Mr. Mackey is fiercely competitive and hates to lose—two traits that help a lot in business.

His odyssey from a long-haired counterculture anticapitalist in the early 1970s to running a company that now has $8 billion in sales and 280 stores—is a remarkable tale in itself. He attended the University of Texas where he studied philosophy and religion. "I never got my college degree," he admits proudly.

He started Whole Foods in 1978 with one store in Austin with $45,000 of seed capital raised from families and friends. "We lost half of it in the first year and then made $5,000 the next year." He wanted to double down and asked the board to put up more money to expand and build bigger stores. "And of course they thought I was nuts. 'You lost half of our money in the first year.'"

The fledgling CEO convinced them that "if we don't grow, we probably won't survive." The first major super store in 1980 was a success "almost by 3 o'clock on the day it opened." It's been an upward trajectory of profits and sales ever since.

"Before I started my business, my political philosophy was that business is evil and government is good. I think I just breathed it in with the culture. Businesses, they're selfish because they're trying to make money."

At age 25, John Mackey was mugged by reality. "Once you start meeting a payroll you have a little different attitude about those things." This insight explains why he thinks it's a shame that so few elected officials have ever run a business. "Most are lawyers," he says, which is why Washington treats companies like cash dispensers.

Mr. Mackey's latest crusade involves traveling to college campuses across the country, trying to persuade young people that business, profits and capitalism aren't forces of evil. He calls his concept "conscious capitalism."

What is that? "It means that business has the potential to have a deeper purpose. I mean, Whole Foods has a deeper purpose," he says, now sounding very much like a philosopher. "Most of the companies I most admire in the world I think have a deeper purpose." He continues, "I've met a lot of successful entrepreneurs. They all started their businesses not to maximize shareholder value or money but because they were pursuing a dream."

Mr. Mackey tells me he is trying to save capitalism: "I think that business has a noble purpose. It's not that there's anything wrong with making money. It's one of the important things that business contributes to society. But it's not the sole reason that businesses exist."

What does he mean by a "noble purpose"? "It means that just like every other profession, business serves society. They produce goods and services that make people's lives better. Doctors heal the sick. Teachers educate people. Architects design buildings. Lawyers promote justice. Whole Foods puts food on people's tables and we improve people's health."

Then he adds: "And we provide jobs. And we provide capital through profits that spur improvements in the world. And we're good citizens in our communities, and we take our citizenship very seriously at Whole Foods."

I ask Mr. Mackey why he doesn't collect a paycheck. "I'm an owner. I have the exact same motivation any shareholder would have in the Whole Foods Market because I'm not drawing a salary from the company. How much money does anybody need?" More to the point, he says, "If the business prospers, I prosper. If the business struggles, I struggle. It's good for morale." He hastens to add that "I'm not saying anybody else should do what I do."

Well, that's not exactly true. Mr. Mackey has been vocal in his opposition to recent CEO salaries. "I do think that it's the responsibility of the leadership of an organization to constrain itself for the good of the organization. If you look at the history of business in America, CEOs used to have much more constraint in compensation and it's gone up tremendously in the last 30 years."

He bemoans the trend that once a Fortune 500 CEO made about 25 times the average worker pay, and now that's climbed to 300 times average employee pay. He says this violates the principle of "internal equity—what your leadership is getting paid relative to everyone else in the organization."

But there's one other institution John Mackey thinks needs a makeover—and that's government. He describes what the Federal Reserve has done with massive money creation as "debauchery of the currency." He thinks the bailouts were a travesty.

"I don't think anybody's too big to fail," he says. "If a business fails, what happens is, there are still assets, and those assets get reorganized. Either new management comes in or it's sold off to another business or it's bid on and the good assets are retained and the bad assets are eliminated. I believe in the dynamic creativity of capitalism, and it's self-correcting, if you just allow it to self-correct."

That's something Washington won't let happen these days, which helps explain why Mr. Mackey felt compelled to write that the Whole Foods health-insurance program is smarter and cheaper than the latest government proposals. As he races out the door to catch a flight to spread the gospel of conscious capitalism elsewhere, I only hope he gets an aisle seat. He deserves it.

Tuesday, October 06, 2009

Thursday, October 01, 2009

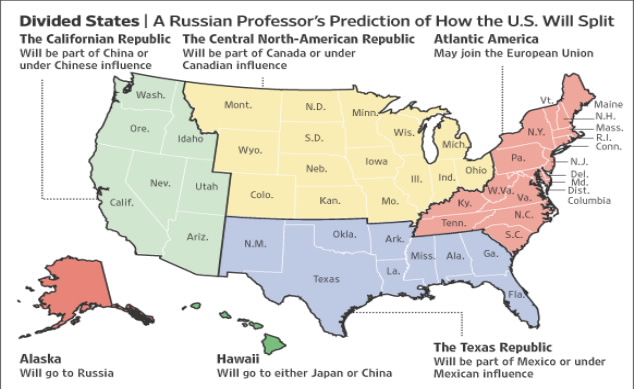

Frozen Shoulder Federalism

Listen to Podcast

Is the United States breaking up? Dan reads a Pat Buchanan commentary that poses that question, so Dan talks about it. Also: Dan extols the virtues of citizen journalism in the wake of the "Acorn" expose.

A Day in the Life of John Q. Public

By George Donnelly(http://www.fr33agents.com/711/a-day-in-the-life-of-john-q-public/)

John gets up at 6 AM and fills his coffee pot with water to prepare his morning coffee. The water is clean and pure because he bought a reverse osmosis filtration system to clean out the lead, iron, sediment, viagra and prozac that comes in from the local government water monopoly.

His Daily Medication

With his first swallow of coffee, he takes his daily medication. He’d like to get the surgery instead, because the pills are slowly damaging his liver and kidneys. But due to government interference in the health care market – causing prices to rise – and the banking cartel’s government-chartered central bank’s debasing of the currency – causing the value of his salary to decline – he can’t afford it.

He smuggles his medication in from Mexico once a month because the government won’t allow it to be sold inside the US. It competes with the product of a large pharmaceutical company who has hired a lot of lobbyists to protect their US market share.

Government-Prohibited Products

John takes responsibility for his own health by preparing oatmeal for breakfast. He uses unpasteurized milk from the dairy down the street, avoiding the allergies and increased risk of heart disease associated with government-mandated pasteurized milk. He sprinkles some organic hemp seed on his oatmeal, a complete protein a friend snuck into the country from Canada because the government bans its cultivation here.

In the morning shower, John reaches for his favorite shampoo. It leaves his hair soft and shiny using only natural ingredients. He uses a special formula invented by a chemist friend and sold out of her garage and at flea markets – until government agents shut her down for operating a laboratory without a license and selling an unapproved healthcare product. John got the last bottle and is milking it.

Dirty Air, Thanks to the Government

John dresses, walks outside and takes a deep breath. The air he breathes is noticeably contaminated because the government subsidizes big buses that belch out dangerous chemicals all day long all over the city. Zero-emission cars aren’t available on the market because the car makers and the oil companies are in bed with the government. They don’t want change.

He walks to the commuter rail station to ride a government-owned train to work. It used to belong to a private company but the government anti-trust laws caused the railway company to fail. He wishes he could drive to work but with the gasoline tax and the overcrowded government roads, he can’t afford it. He carries an illegal firearm on the train due to a recent mugging and is afraid someone will find out about it.

Sentenced to Wage Slavery … by the Government

John begins his workday. He has a boring job with average pay, medical benefits, retirement, paid holidays and vacation because that’s what the government mandates. He’d rather get it all in cash so he can choose his own health care and retirement plans. He’d like to start a business at home from his baking hobby but the government mandates he rent a separate space and purchase industrial baking appliances in order to get started. He might be able to do that – and quit his wage slave job in the city – if the government didn’t take 40 per cent of his income right off the top.

If John is hurt on the job or becomes unemployed, he’ll get a workers’ compensation or unemployment check because he joined a local mutual aid society and voluntarily pays dues into it every week. But it’s the last one in his state and its future is uncertain because the government started competing services and can legally force people to pay for them. His mutual aid society pays better and costs less but most people can’t afford to pay for the same thing twice.

Escaping to Gold

It’s lunchtime so John heads to the coin shop to buy some gold. John knows that due to the constant expansion of the money supply by the banking cartel’s government-chartered central bank, the value of John’s dollars falls almost every day. Now that the FDIC is insolvent, he worries that economic collapse is around the corner and knows gold has always been a good store of value.

John paid too much for his house because he bought at the peak of the government-created bubble. Thanks to Fannie, Freddie, the FHA, the Fed and others in government, his house may soon be worth less than his mortgage. He had to take out government loans for college due to government higher education subsidies, which incentivize schools to charge more, because they’ll get more from the government if they do.

Government Putting His Dad out of Business

John is home from work. He plans to visit his father this evening at his home in the country. His was the third generation to live on the property. But the EPA and OSHA are trying to shut down the family scrap yard business, claiming it violates hundreds of federal regulations. The local township raised taxes on the property recently and is trying to re-zone it to render the family business illegal.

He is happy to see his father, who would like to retire, but can’t. Due to self-employment taxes, his dad paid twice into Social Security but can only get the same meager check as anyone else. With the rising costs of health care – due to government subsidies and regulatory interference – he’s afraid his first medical emergency will wipe out his hard-earned savings.

“The Free Market is a Failure”

John gets back in his car for the ride home, and turns on a radio talk show. The radio host tells him that we need more government “solutions” to our problems, that government bureaucrats know what is best for him and the free market is a failure.

He doesn’t mention that the beloved government bureaucrats and politicians have undermined every protection and benefit John enjoys throughout his day and are destroying the best things in his life.

On Palestinian Civil Disobedience

A simple google search with the words Palestinian and violence yields over 8.5 million pages, while a search with the words Palestinian and civil disobedience generates only 80,000 pages.

by Neve Gordon

(http://www.commondreams.org/view/2009/09/28-1)

Sometime in 1846, Henry David Thoreau spent a night in jail because he refused to pay his taxes. This was his way of opposing the Mexican-American War as well as the institution of slavery. A few years later he published the essay Civil Disobedience, which has since been read by millions of people, including many Israelis and Palestinians.

Kobi Snitz read the book. He is an Israeli anarchist who is currently serving a 20 day sentence for refusing to pay a 2,000 shekel fine.

Thirty-eight year-old Snitz was arrested with other activists in the small Palestinian village of Kharbatha back in 2004 while trying to prevent the demolition of the home of a prominent member of the local popular committee. The demolition, so it seems, was carried out both to intimidate and punish the local leader who had, just a couple of weeks earlier, began organizing weekly demonstrations against the annexation wall. Both the demonstrations and the attempt to stop the demolition were acts of civil disobedience.

In a letter sent to friends the night before his incarceration, Snitz writes that "I and the others who were arrested with me are guilty of nothing except not doing more to oppose the state's truly criminal policies." Snitz also explains that paying the fine is an acknowledgment of guilt which he finds demeaning. Finally, he concludes his epistle by insisting that his punishment is trivial when compared to the punishment meted out to Palestinian teenagers who have resisted the occupation. These thirteen, fourteen, fifteen and sixteen year olds, he claims, are often detained for 20 days before the legal process even begins.

Snitz is not exaggerating.

In a recent report, the Palestinian human rights organizations Stop the Wall and Addameer document the forms of repression Israel has deployed against villages that have resisted the annexation of their land. The two rights groups show that once a village decides to struggle against the annexation barrier the entire community is punished. In addition to home demolitions, curfews and other forms of movement restriction, the Israeli military forces consistently uses violence against the protestors-and most often targets the youth-- beating, tear-gassing as well as deploying both lethal and "non-lethal" ammunition against them.

Since 2004, nineteen people, about half of them children, have been killed in protests against the barrier. The rights groups found that in four small Palestinian villages -- Bil'in, Ni'lin, Ma'sara and Jayyous -- 1,566 Palestinians have been injured in demonstrations against the wall. In five villages alone, 176 Palestinians have been arrested for protesting against the annexation, with children and youth specifically targeted during these arrest campaigns. The actual numbers of those who were injured and arrested are no doubt greater considering that these are just the incidents that took place in a few villages.

Each number has a name and a story. Consider, for example, the arrest of sixteen year-old Mohammed Amar Hussan Nofal who was detained along with about 65 other people from his village Jayyous on February 18, 2009. According to his testimony, he was initially interrogated for two and a half hours in the village school.

"They asked me why I participated in the demonstrations, but I tried to deny [that I had]. Then they asked me why I threw a Molotov cocktail [at] them. I said I never had, which was true. My parents were there and witnessed [what happened]. They can confirm I never [threw a Molotov cocktail]. I later confessed to [having been at] demonstrations, but not [to having] thrown a Molotov cocktail."

After being beaten for refusing to hold up a paper with numbers and Hebrew words on it in order to be photographed, Nofal was sent to Kedumim and was interrogated for several more hours. During this interrogation Captain Faisal (a pseudonym of a secret service officer) tried to recruit the teenager to become a collaborator.

"The Captain threatened that he would arrest my parents and my whole family if I did not collaborate. I said they could arrest [my family] any time, [but] it would be worse to become a spy. He then said they would confiscate my family's permits so they could not pick olives."

Nofal's only crime was protesting against the expropriation of his ancestral lands. He spent three months in prison, during which time the Civil Administration decided to punish his family as well and refused to renew their permits to work in Israel.

When compared to Nofal and thousands of other Palestinians, Kobi Snitz is indeed paying a small price. But his act is symbolically important, not only due to his solidarity with his Palestinian partners, but also because he, like thousands of Palestinians, has decided to follow the lead of Henry David Thoreau and to commit acts of civil disobedience in order to resist Israel's immoral policies and the subjugation of a whole people.

The problem is that the world knows very little about these acts. A simple google search with the words Palestinian and violence yields over 8.5 million pages, while a search with the words Palestinian and civil disobedience generates only 80,000 pages - this despite the fact that for several years now Palestinians have been carrying out daily acts of civil disobedience against the Israeli occupation.

Thoreau, I believe, would have been proud of Nofal, Snitz and their fellow activists. It is crucial that the media and international community recognize their heroism as well.

Neve Gordon teaches politics at Ben-Gurion University. Read about his new book, Israel's Occupation (due out this fall from the University of California Press), and more at israelsoccupation.info.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Death Panels and the Fear of Dying

(http://www.wpr.org/hereonearth/archive_090914k.cfm)

Listen to Podcast

When Georgia Weithe's father was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 1997, she approached his impending death with absolute terror. To her great surprise, the experience deepened her life in ways she could not have anticipated, and she came to the conclusion that death is a teacher and a friend. Georgia is the author of Shining Moments: Finding Hope in Facing Death.

A Four-Step Health-Care Solution

It's true that the U.S. health care system is a mess, but this demonstrates not market but government failure. To cure the problem requires not different or more government regulations and bureaucracies, as self-serving politicians want us to believe, but the elimination of all existing government controls.

It's time to get serious about health care reform. Tax credits, vouchers, and privatization will go a long way toward decentralizing the system and removmg unnecessary burdens from business. But four additional steps must also be taken:

1. Eliminate all licensing requirements for medical schools, hospitals, pharmacies, and medical doctors and other health care personnel. Their supply would almost instantly increase, prices would fall, and a greater variety of health care services would appear on the market.

Competing voluntary accreditation agencies would take the place of compulsory government licensing--if health care providers believe that such accreditation would enhance their own reputation, and that their consumers care about reputation, and are willing to pay for it.

Because consumers would no longer be duped into believing that there is such a thing as a "national standard" of health care, they will increase their search costs and make more discriminating health care choices.

2. Eliminate all government restrictions on the production and sale of pharmaceutical products and medical devices. This means no more Food and Drug Administration, which presently hinders innovation and increases costs.

Costs and prices would fall, and a wider variety of better products would reach the market sooner. The market would force consumers to act in accordance with their own--rather than the government's--risk assessment. And competing drug and device manufacturers and sellers, to safeguard against product liability suits as much as to attract customers, would provide increasingly better product descriptions and guarantees.

3. Deregulate the health insurance industry. Private enterprise can offer insurance against events over whose outcome the insured possesses no control. One cannot insure oneself against suicide or bankruptcy, for example, because it is in one's own hands to bring these events about.

Because a person's health, or lack of it, lies increasingly within his own control, many, if not most health risks, are actually uninsurable. "Insurance" against risks whose likelihood an individual can systematically influence falls within that person's own responsibility.

All insurance, moreover, involves the pooling of individual risks. It implies that insurers pay more to some and less to others. But no one knows in advance, and with certainty, who the "winners" and "losers" will be. "Winners" and "losers" are distributed randomly, and the resulting income redistribution is unsystematic. If "winners" or "losers" could be systematically predicted, "losers" would not want to pool their risk with "winners," but with other "losers," because this would lower their insurance costs. I would not want to pool my personal accident risks with those of professional football players, for instance, but exclusively with those of people in circumstances similar to my own, at lower costs.

Because of legal restrictions on the health insurers' right of refusal--to exclude any individual risk as uninsurable--the present health-insurance system is only partly concerned with insurance. The industry cannot discriminate freely among different groups' risks.

As a result, health insurers cover a multitude of uninnsurable risks, alongside, and pooled with, genuine insurance risks. They do not discriminate among various groups of people which pose significantly different insurance risks. The industry thus runs a system of income redistribution--benefiting irresponsible actors and high-risk groups at the expense of responsible individuals and low risk groups. Accordingly the industry's prices are high and ballooning.

To deregulate the industry means to restore it to unrestricted freedom of contract: to allow a health insurer to offer any contract whatsoever, to include or exclude any risk, and to discriminate among any groups of individuals. Uninsurable risks would lose coverage, the variety of insurance policies for the remaining coverage would increase, and price differentials would reflect genuine insurance risks. On average, prices would drastically fall. And the reform would restore individual responsibility in health care.

4. Eliminate all subsidies to the sick or unhealthy. Subsidies create more of whatever is being subsidized. Subsidies for the ill and diseased breed illness and disease, and promote carelessness, indigence, and dependency. If we eliminate them, we would strengthen the will to live healthy lives and to work for a living. In the first instance, that means abolishing Medicare and Medicaid.

Only these four steps, although drastic, will restore a fully free market in medical provision. Until they are adopted, the industry will have serious problems, and so will we, its consumers.

Poetry Instead

Listen to Podcast

Patricia Smith is the four-time champion of the National Poetry Slam. Jay Parini discusses the power of poetry and how it especially empowers young people in troubled times. Gioia Timpanelli uses her poetic sensibility to write prose novels and talks about the two kinds of writing. Les Murray is considered by many literary critics to be the greatest living poet in English today.

Patricia Smith is an African American who is the four-time champion of the National Poetry Slam. Her book ""Blood Dazzler"" was nominated for the 2008 National Book Award. She talks about her work with Steve Paulson and performs several poems.

Jay Parini teaches poetry at Middlebury College, and is the author of ""Why Poetry Matters."" He talks with Jim Fleming about Jim Fleming about the power of poetry and how it especially empowers young people in troubled times.

Gioia Timpanelli uses her poetic sensibility to write prose novels. She talks with Anne Strainchamps about the two kinds of writing, and her story ""What Makes a Child Lucky."" And we hear selections from the story.

Australian Les Murray is considered by many literary critics to be the greatest living poet in English today. He rarely gives interviews, but spoke with Steve Paulson and read several of his poems. His latest book of poetry is called ""The Bi-Plane Houses.

The Holy Grail of the Unconscious

By SARA CORBETT

(http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/20/magazine/20jung-t.html?pagewanted=all)This is a story about a nearly 100-year-old book, bound in red leather, which has spent the last quarter century secreted away in a bank vault in Switzerland. The book is big and heavy and its spine is etched with gold letters that say “Liber Novus,” which is Latin for “New Book.” Its pages are made from thick cream-colored parchment and filled with paintings of otherworldly creatures and handwritten dialogues with gods and devils. If you didn’t know the book’s vintage, you might confuse it for a lost medieval tome.

And yet between the book’s heavy covers, a very modern story unfolds. It goes as follows: Man skids into midlife and loses his soul. Man goes looking for soul. After a lot of instructive hardship and adventure — taking place entirely in his head — he finds it again.

Some people feel that nobody should read the book, and some feel that everybody should read it. The truth is, nobody really knows. Most of what has been said about the book — what it is, what it means — is the product of guesswork, because from the time it was begun in 1914 in a smallish town in Switzerland, it seems that only about two dozen people have managed to read or even have much of a look at it.

Of those who did see it, at least one person, an educated Englishwoman who was allowed to read some of the book in the 1920s, thought it held infinite wisdom — “There are people in my country who would read it from cover to cover without stopping to breathe scarcely,” she wrote — while another, a well-known literary type who glimpsed it shortly after, deemed it both fascinating and worrisome, concluding that it was the work of a psychotic.

So for the better part of the past century, despite the fact that it is thought to be the pivotal work of one of the era’s great thinkers, the book has existed mostly just as a rumor, cosseted behind the skeins of its own legend — revered and puzzled over only from a great distance.

Which is why one rainy November night in 2007, I boarded a flight in Boston and rode the clouds until I woke up in Zurich, pulling up to the airport gate at about the same hour that the main branch of the Union Bank of Switzerland, located on the city’s swanky Bahnhofstrasse, across from Tommy Hilfiger and close to Cartier, was opening its doors for the day. A change was under way: the book, which had spent the past 23 years locked inside a safe deposit box in one of the bank’s underground vaults, was just then being wrapped in black cloth and loaded into a discreet-looking padded suitcase on wheels. It was then rolled past the guards, out into the sunlight and clear, cold air, where it was loaded into a waiting car and whisked away.

THIS COULD SOUND, I realize, like the start of a spy novel or a Hollywood bank caper, but it is rather a story about genius and madness, as well as possession and obsession, with one object — this old, unusual book — skating among those things. Also, there are a lot of Jungians involved, a species of thinkers who subscribe to the theories of Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and author of the big red leather book. And Jungians, almost by definition, tend to get enthused anytime something previously hidden reveals itself, when whatever’s been underground finally makes it to the surface.

Carl Jung founded the field of analytical psychology and, along with Sigmund Freud, was responsible for popularizing the idea that a person’s interior life merited not just attention but dedicated exploration — a notion that has since propelled tens of millions of people into psychotherapy. Freud, who started as Jung’s mentor and later became his rival, generally viewed the unconscious mind as a warehouse for repressed desires, which could then be codified and pathologized and treated. Jung, over time, came to see the psyche as an inherently more spiritual and fluid place, an ocean that could be fished for enlightenment and healing.

Whether or not he would have wanted it this way, Jung — who regarded himself as a scientist — is today remembered more as a countercultural icon, a proponent of spirituality outside religion and the ultimate champion of dreamers and seekers everywhere, which has earned him both posthumous respect and posthumous ridicule. Jung’s ideas laid the foundation for the widely used Myers-Briggs personality test and influenced the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. His central tenets — the existence of a collective unconscious and the power of archetypes — have seeped into the larger domain of New Age thinking while remaining more at the fringes of mainstream psychology.

A big man with wire-rimmed glasses, a booming laugh and a penchant for the experimental, Jung was interested in the psychological aspects of séances, of astrology, of witchcraft. He could be jocular and also impatient. He was a dynamic speaker, an empathic listener. He had a famously magnetic appeal with women. Working at Zurich’s Burghölzli psychiatric hospital, Jung listened intently to the ravings of schizophrenics, believing they held clues to both personal and universal truths. At home, in his spare time, he pored over Dante, Goethe, Swedenborg and Nietzsche. He began to study mythology and world cultures, applying what he learned to the live feed from the unconscious — claiming that dreams offered a rich and symbolic narrative coming from the depths of the psyche. Somewhere along the way, he started to view the human soul — not just the mind and the body — as requiring specific care and development, an idea that pushed him into a province long occupied by poets and priests but not so much by medical doctors and empirical scientists.

Jung soon found himself in opposition not just to Freud but also to most of his field, the psychiatrists who constituted the dominant culture at the time, speaking the clinical language of symptom and diagnosis behind the deadbolts of asylum wards. Separation was not easy. As his convictions began to crystallize, Jung, who was at that point an outwardly successful and ambitious man with a young family, a thriving private practice and a big, elegant house on the shores of Lake Zurich, felt his own psyche starting to teeter and slide, until finally he was dumped into what would become a life-altering crisis.

What happened next to Carl Jung has become, among Jungians and other scholars, the topic of enduring legend and controversy. It has been characterized variously as a creative illness, a descent into the underworld, a bout with insanity, a narcissistic self-deification, a transcendence, a midlife breakdown and an inner disturbance mirroring the upheaval of World War I. Whatever the case, in 1913, Jung, who was then 38, got lost in the soup of his own psyche. He was haunted by troubling visions and heard inner voices. Grappling with the horror of some of what he saw, he worried in moments that he was, in his own words, “menaced by a psychosis” or “doing a schizophrenia.”

He later would compare this period of his life — this “confrontation with the unconscious,” as he called it — to a mescaline experiment. He described his visions as coming in an “incessant stream.” He likened them to rocks falling on his head, to thunderstorms, to molten lava. “I often had to cling to the table,” he recalled, “so as not to fall apart.”

Had he been a psychiatric patient, Jung might well have been told he had a nervous disorder and encouraged to ignore the circus going on in his head. But as a psychiatrist, and one with a decidedly maverick streak, he tried instead to tear down the wall between his rational self and his psyche. For about six years, Jung worked to prevent his conscious mind from blocking out what his unconscious mind wanted to show him. Between appointments with patients, after dinner with his wife and children, whenever there was a spare hour or two, Jung sat in a book-lined office on the second floor of his home and actually induced hallucinations — what he called “active imaginations.” “In order to grasp the fantasies which were stirring in me ‘underground,’ ” Jung wrote later in his book “Memories, Dreams, Reflections,” “I knew that I had to let myself plummet down into them.” He found himself in a liminal place, as full of creative abundance as it was of potential ruin, believing it to be the same borderlands traveled by both lunatics and great artists.

Jung recorded it all. First taking notes in a series of small, black journals, he then expounded upon and analyzed his fantasies, writing in a regal, prophetic tone in the big red-leather book. The book detailed an unabashedly psychedelic voyage through his own mind, a vaguely Homeric progression of encounters with strange people taking place in a curious, shifting dreamscape. Writing in German, he filled 205 oversize pages with elaborate calligraphy and with richly hued, staggeringly detailed paintings.

What he wrote did not belong to his previous canon of dispassionate, academic essays on psychiatry. Nor was it a straightforward diary. It did not mention his wife, or his children, or his colleagues, nor for that matter did it use any psychiatric language at all. Instead, the book was a kind of phantasmagoric morality play, driven by Jung’s own wish not just to chart a course out of the mangrove swamp of his inner world but also to take some of its riches with him. It was this last part — the idea that a person might move beneficially between the poles of the rational and irrational, the light and the dark, the conscious and the unconscious — that provided the germ for his later work and for what analytical psychology would become.

The book tells the story of Jung trying to face down his own demons as they emerged from the shadows. The results are humiliating, sometimes unsavory. In it, Jung travels the land of the dead, falls in love with a woman he later realizes is his sister, gets squeezed by a giant serpent and, in one terrifying moment, eats the liver of a little child. (“I swallow with desperate efforts — it is impossible — once again and once again — I almost faint — it is done.”) At one point, even the devil criticizes Jung as hateful.

He worked on his red book — and he called it just that, the Red Book — on and off for about 16 years, long after his personal crisis had passed, but he never managed to finish it. He actively fretted over it, wondering whether to have it published and face ridicule from his scientifically oriented peers or to put it in a drawer and forget it. Regarding the significance of what the book contained, however, Jung was unequivocal. “All my works, all my creative activity,” he would recall later, “has come from those initial fantasies and dreams.”

Jung evidently kept the Red Book locked in a cupboard in his house in the Zurich suburb of Küsnacht. When he died in 1961, he left no specific instructions about what to do with it. His son, Franz, an architect and the third of Jung’s five children, took over running the house and chose to leave the book, with its strange musings and elaborate paintings, where it was. Later, in 1984, the family transferred it to the bank, where since then it has fulminated as both an asset and a liability.

Anytime someone did ask to see the Red Book, family members said, without hesitation and sometimes without decorum, no. The book was private, they asserted, an intensely personal work. In 1989, an American analyst named Stephen Martin, who was then the editor of a Jungian journal and now directs a Jungian nonprofit foundation, visited Jung’s son (his other four children were daughters) and inquired about the Red Book. The question was met with a vehemence that surprised him. “Franz Jung, an otherwise genial and gracious man, reacted sharply, nearly with anger,” Martin later wrote in his foundation’s newsletter, saying “in no uncertain terms” that Martin could not “see the Red Book, nor could he ever imagine that it would be published.”

And yet, Carl Jung’s secret Red Book — scanned, translated and footnoted — will be in stores early next month, published by W. W. Norton and billed as the “most influential unpublished work in the history of psychology.” Surely it is a victory for someone, but it is too early yet to say for whom.

STEPHEN MARTIN IS a compact, bearded man of 57. He has a buoyant, irreverent wit and what feels like a fully intact sense of wonder. If you happen to have a conversation with him anytime before, say, 10 a.m., he will ask his first question — “How did you sleep?” — and likely follow it with a second one — “Did you dream?” Because for Martin, as it is for all Jungian analysts, dreaming offers a barometric reading of the psyche. At his house in a leafy suburb of Philadelphia, Martin keeps five thick books filled with notations on and interpretations of all the dreams he had while studying to be an analyst 30 years ago in Zurich, under the tutelage of a Swiss analyst then in her 70s named Liliane Frey-Rohn. These days, Martin stores his dreams on his computer, but his dream life is — as he says everybody’s dream life should be — as involving as ever.

Even as some of his peers in the Jungian world are cautious about regarding Carl Jung as a sage — a history of anti-Semitic remarks and his sometimes patriarchal views of women have caused some to distance themselves — Martin is unapologetically reverential. He keeps Jung’s 20 volumes of collected works on a shelf at home. He rereads “Memories, Dreams, Reflections” at least twice a year. Many years ago, when one of his daughters interviewed him as part of a school project and asked what his religion was, Martin, a nonobservant Jew, answered, “Oh, honey, I’m a Jungian.”

The first time I met him, at the train station in Ardmore, Pa., Martin shook my hand and thoughtfully took my suitcase. “Come,” he said. “I’ll take you to see the holy hankie.” We then walked several blocks to the office where Martin sees clients. The room was cozy and cavelike, with a thick rug and walls painted a deep, handsome shade of blue. There was a Mission-style sofa and two upholstered chairs and an espresso machine in one corner.

Several mounted vintage posters of Zurich hung on the walls, along with framed photographs of Carl Jung, looking wise and white-haired, and Liliane Frey-Rohn, a round-faced woman smiling maternally from behind a pair of severe glasses.

Martin tenderly lifted several first-edition books by Jung from a shelf, opening them so I could see how they had been inscribed to Frey-Rohn, who later bequeathed them to Martin. Finally, we found ourselves standing in front of a square frame hung on the room’s far wall, another gift from his former analyst and the centerpiece of Martin’s Jung arcana. Inside the frame was a delicate linen square, its crispness worn away by age — a folded handkerchief with the letters “CGJ” embroidered neatly in one corner in gray. Martin pointed. “There you have it,” he said with exaggerated pomp, “the holy hankie, the sacred nasal shroud of C. G. Jung.”

In addition to practicing as an analyst, Martin is the director of the Philemon Foundation, which focuses on preparing the unpublished works of Carl Jung for publication, with the Red Book as its central project. He has spent the last several years aggressively, sometimes evangelistically, raising money in the Jungian community to support his foundation. The foundation, in turn, helped pay for the translating of the book and the addition of a scholarly apparatus — a lengthy introduction and vast network of footnotes — written by a London-based historian named Sonu Shamdasani, who serves as the foundation’s general editor and who spent about three years persuading the family to endorse the publication of the book and to allow him access to it.

Given the Philemon Foundation’s aim to excavate and make public C. G. Jung’s old papers — lectures he delivered at Zurich’s Psychological Club or unpublished letters, for example — both Martin and Shamdasani, who started the foundation in 2003, have worked to develop a relationship with the Jung family, the owners and notoriously protective gatekeepers of Jung’s works. Martin echoed what nearly everybody I met subsequently would tell me about working with Jung’s descendants. “It’s sometimes delicate,” he said, adding by way of explanation, “They are very Swiss.”

What he likely meant by this was that the members of the Jung family who work most actively on maintaining Jung’s estate tend to do things carefully and with an emphasis on privacy and decorum and are on occasion taken aback by the relatively brazen and totally informal way that American Jungians — who it is safe to say are the most ardent of all Jungians — inject themselves into the family’s business. There are Americans knocking unannounced on the door of the family home in Küsnacht; Americans scaling the fence at Bollingen, the stone tower Jung built as a summer residence farther south on the shore of Lake Zurich. Americans pepper Ulrich Hoerni, one of Jung’s grandsons who manages Jung’s editorial and archival matters through a family foundation, almost weekly with requests for various permissions. The relationship between the Jungs and the people who are inspired by Jung is, almost by necessity, a complex symbiosis. The Red Book — which on one hand described Jung’s self-analysis and became the genesis for the Jungian method and on the other was just strange enough to possibly embarrass the family — held a certain electrical charge. Martin recognized the descendants’ quandary. “They own it, but they haven’t lived it,” he said, describing Jung’s legacy. “It’s very consternating for them because we all feel like we own it.” Even the old psychiatrist himself seemed to recognize the tension. “Thank God I am Jung,” he is rumored once to have said, “and not a Jungian.”

“This guy, he was a bodhisattva,” Martin said to me that day. “This is the greatest psychic explorer of the 20th century, and this book tells the story of his inner life.” He added, “It gives me goose bumps just thinking about it.” He had at that point yet to lay eyes on the book, but for him that made it all the more tantalizing. His hope was that the Red Book would “reinvigorate” Jungian psychology, or at the very least bring himself personally closer to Jung. “Will I understand it?” he said. “Probably not. Will it disappoint? Probably. Will it inspire? How could it not?” He paused a moment, seeming to think it through. “I want to be transformed by it,” he said finally. “That’s all there is.”

IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND and decode the Red Book — a process he says required more than five years of concentrated work — Sonu Shamdasani took long, rambling walks on London’s Hampstead Heath. He would translate the book in the morning, then walk miles in the park in the afternoon, his mind trying to follow the rabbit’s path Jung had forged through his own mind.

Shamdasani is 46. He has thick black hair, a punctilious eye for detail and an understated, even somnolent, way of speaking. He is friendly but not particularly given to small talk. If Stephen Martin is — in Jungian terms — a “feeling type,” then Shamdasani, who teaches at the University College London’s Wellcome Trust Center for the History of Medicine and keeps a book by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus by his sofa for light reading, is a “thinking type.” He has studied Jungian psychology for more than 15 years and is particularly drawn to the breadth of Jung’s psychology and his knowledge of Eastern thought, as well as the historical richness of his era, a period when visionary writing was more common, when science and art were more entwined and when Europe was slipping into the psychic upheaval of war. He tends to be suspicious of interpretive thinking that’s not anchored by hard fact — and has, in fact, made a habit of attacking anybody he deems guilty of sloppy scholarship — and also maintains a generally unsentimental attitude toward Jung. Both of these qualities make him, at times, awkward company among both Jungians and Jungs.

The relationship between historians and the families of history’s luminaries is, almost by nature, one of mutual disenchantment. One side works to extract; the other to protect. One pushes; one pulls. Stephen Joyce, James Joyce’s literary executor and last living heir, has compared scholars and biographers to “rats and lice.” Vladimir Nabokov’s son Dmitri recently told an interviewer that he considered destroying his father’s last known novel in order to rescue it from the “monstrous nincompoops” who had already picked over his father’s life and works. T. S. Eliot’s widow, Valerie Fletcher, has actively kept his papers out of the hands of biographers, and Anna Freud was, during her lifetime, notoriously selective about who was allowed to read and quote from her father’s archives.

Even against this backdrop, the Jungs, led by Ulrich Hoerni, the chief literary administrator, have distinguished themselves with their custodial vigor. Over the years, they have tried to interfere with the publication of books perceived to be negative or inaccurate (including one by the award-winning biographer Deirdre Bair), engaged in legal standoffs with Jungians and other academics over rights to Jung’s work and maintained a state of high agitation concerning the way C. G. Jung is portrayed. Shamdasani was initially cautious with Jung’s heirs. “They had a retinue of people coming to them and asking to see the crown jewels,” he told me in London this summer. “And the standard reply was, ‘Get lost.’ ”

Shamdasani first approached the family with a proposal to edit and eventually publish the Red Book in 1997, which turned out to be an opportune moment. Franz Jung, a vehement opponent of exposing Jung’s private side, had recently died, and the family was reeling from the publication of two controversial and widely discussed books by an American psychologist named Richard Noll, who proposed that Jung was a philandering, self-appointed prophet of a sun-worshiping Aryan cult and that several of his central ideas were either plagiarized or based upon falsified research.