Half a Decade of War: Five Years After Iraq Invasion, Soldiers Testify at Winter Soldier Hearings

Real Video StreamReal Audio StreamMP3 Download(

View Original)

Five years ago tonight, on March 19, 2003, the US launched the invasion of Iraq. Half a decade later, as the occupation continues with no end in sight, some of the most powerful voices against the war have been the men and women who have fought in it. For four days this past weekend, soldiers convened at the National Labor College in Silver Spring, Maryland for Winter Soldier, an eyewitness account of the war and occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan. We broadcast their voices.

Camilo Mejia, former staff sergeant who served six months in Iraq in 2003 with the Florida National Guard. After a brief leave, he refused to return. He was court-martialed and served nearly a year in prison. He is now the chair of the board of Iraq Veterans Against the War.

Mike Totten, Former US Army specialist who served with the 716th MP Battalion in the 101st Airborne and was deployed to Iraq in April 2003 until April 2004.

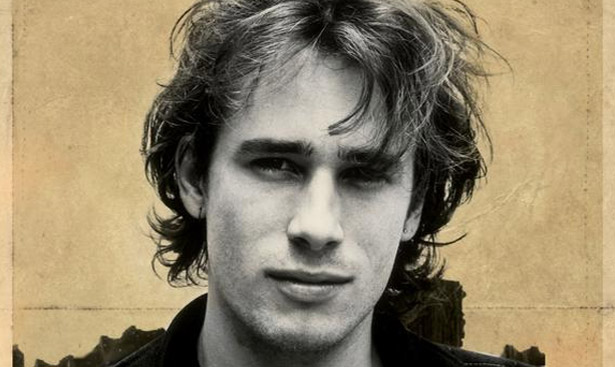

Kevin and Joyce Lucey, their son, Marine Lance Corporal Jeffrey Lucey, served five months in Iraq with the 6th Motor Transport Battalion. Almost a year later, he committed suicide, in June 2004. He was twenty-three years old.

Tanya Austin, Arab linguist in Military Intelligence.

Jeffrey Smith, served in Iraq in May 2003 and was honorably discharged in January 2004.

AMY GOODMAN: Five years ago tonight, on March 19th, 2003, the US began bombing Baghdad. The invasion was on. Six weeks later, President Bush stood under a banner reading "Mission Accomplished" and declared an end to major military combat operations in Iraq. Now, half a decade later, the war continues with no end in sight.

In a speech today to mark the fifth anniversary, the President, who leaves office in less than eleven months, will again give an upbeat assessment of the war. According to released excerpts of his address, Bush will insist the so-called troop surge in Iraq has opened the door to a "major strategic victory in the broader war on terror."

But by most accounts, the war has been an unmitigated disaster. Up to one million Iraqis have been killed, with no estimates on the number of those wounded. Up to 2.5 million people are estimated to be displaced inside Iraq, and more than two million have fled to neighboring countries. Meanwhile, nearly 4,000 US soldiers have been killed and tens of thousands more wounded. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz estimates the overall cost of this war will be $3 trillion.

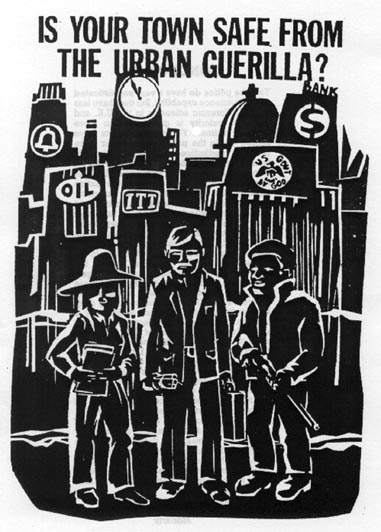

To mark this fifth anniversary of the invasion, hundreds of marches, sit-ins and other protests are planned around the country. In Washington, D.C., demonstrators plan to block the entrance to the Internal Revenue Service and to disrupt the offices of K Street lobbyists who represent military contractors and oil companies profiting from the war. In New York, protesters from the Granny Peace Brigade will hold a "knit-in" at the Times Square military recruitment center. In Chicago, a large rally and protest march is planned, while in Louisville, Kentucky, protesters will read aloud the names of some of the US troops killed in the war. And college students from New Jersey to North Dakota are planning walkouts across their campuses.

But perhaps some of the most powerful voices against the Iraq war have been the soldiers who have fought it. For four days this past weekend, soldiers convened at the National Labor College in Silver Spring, Maryland for Winter Soldier, eyewitness accounts of the war and occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan. The corporate media largely ignored the story. For the past few days, we’ve been broadcasting their voices. Today, we continue with former Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejia.

CAMILO MEJIA: My name is Camilo Mejia. I joined the military in 1995 as an infantryman, and I deployed to the Middle East in March of ’03, first to Jordan and then to Iraq in April of that same year.

The first mission that we had when we got to Iraq was at this place called Al Assad, and our job there was basically to run a prisoner of war camp. And at this prisoner of war camp, our job was basically to keep prisoners who had been deemed enemy combatants sleep-deprived for periods of up to seventy-two hours in order to, quote-unquote, "soften them up for interrogation." And the way we did that was by yelling at them.

So my first question to the people who were training us on how to do this was, you know, "How do they understand? I mean, they don’t speak English." And he said, "Well, they’re just like animals. They’re just like dogs. If you keep yelling at them, it doesn’t matter what language you’re yelling at them in, they’re going to get the point. If you yell at them, ’Get up!’ enough times, you know, just like a dog gets up, they’ll get up. If you tell them to move left, eventually they’ll get it and they’ll move left. And they said, "But that’s not going to always work, because they’re so tired." By the way, they were hooded with sandbags, and they were tied with plastic restraints, barefoot, and circled around with concertina wire. So they were not only being deprived of sleep, but also of light and sense of space.

And so, the next thing that we did was to hit the wall next to them with a sledgehammer to create this explosion-like sound to scare them. And when that didn’t work, the next step was to put a gun to their heads and to charge it as if to execute them. Basically we were performing mock executions to scare these men. And every now and then that wouldn’t work, so you would grab the person who was not obeying and put him in a chamber and hit the wall next to this person to basically drive him insane and get them to obey.

Another time I remember, we were at a traffic control point, and we had received reports of ambulances being used to deliver explosives. So we were really close to the only—we were actually blocking the only road that led to the hospital, to the local hospital, and this ambulance came upon our traffic control point. And they told us that we could not let the ambulance through. There was a pregnant woman who needed to get to the hospital, but they said we don’t know if that’s a pregnant woman or if this is, you know, a van full of explosives and it’s going to explode. So we basically turned it back. And I remember at the time I felt bad, and I wanted to send a team to basically—to search the van and to establish whether it was—there really was a pregnant woman, but I kept thinking of the images of the ambulance exploding in the perimeter and killing a bunch of our people, so I basically made the decision not to search the van and to just turn it away.

Another time, we were again at the traffic control point, and we were attacked. And we were in the middle of a firefight, and then they stopped shooting at us. And we began to assess damage and to, you know, collect our wounded. And there were a lot of Iraqi civilians who were killed. And from this car came a voice that was calling me: "Mister! Mister!" And I approached the car. And again, we had this Intel report saying that at traffic control points, you know, people will call you and say, you know, "Help me!" Help me!" and then they’ll shoot you or they’ll—the vehicle will blow up. So when I’m approaching this car right after this firefight—and then after this happened, then they began shooting at us again. But as I approached this car, I saw that there was this man, this young man at the driver’s seat, and that there were two older gentlemen who were also wounded, one pretty badly, and who were saying, you know, "Help me! Help me!" And at the time, I could—all I could think about was that Intel report saying, you know, these people are trying to kill you. So I basically had my rifle aimed at them and was about to shoot them until somebody came and said, "Sergeant, Sergeant, you know, they’re wounded. Don’t shoot at them."

But I guess what I’m trying to say is that it’s really—it’s almost impossible to act upon your morality in a situation like that when you have been fed all this information that, you know, these people are out there to kill you. And what you do is you basically remove the humanity from them to make it easier to oppress them, to brutalize them, to beat them. And in doing so, you remove the humanity from yourself, because you cannot act as a human being and do all of these things.

And one last incident that I want to talk about was the first time that I opened fire on a human being, and this happened right after a protest. They were throwing grenades at us, and they said, you know, if anybody throws a grenade, you know, open fire on them. So we saw this coming, and I saw this young man basically—you know, his arm was swinging, and he had a black object in his hand, which was indeed a grenade. And I remember seeing all of this through the rear aperture of my M16 rifle sight, and I remember when we opened fire on him. And then I remember when two men came from the crowd and basically dragged him by his shoulders back into the crowd after we killed him. And after that incident, I remember going into a room by myself and counting the rounds that I had left in my magazine, and I had nineteen rounds left, which meant that I had fired eleven rounds at this person. And—but yet, I had no recollection of hitting him or him going down, him dropping, him dying.

I just—there was this blank space in my memory, which is a blank space that I have for other experiences, like this time when this child was basically riding in the passenger seat with his father, and we decapitated his father with a machinegun. And when we went down to the low ground to search for enemy wounded, I remember seeing this young person standing next to this body that was decapitated. And when I think about it, I cannot remember the expression on the child’s face. I cannot remember that he was a child. I only know this because people told me later on that was the man’s son, the man’s young son, who was standing next to the body.

And it’s because not only—it’s not enough to—to dehumanize the enemy by means of your military background or training or the indoctrination or the heat and the fatigue and the intensity of the environment, but there are times when it is so hard to deal with these experiences that I suppose your own body, your own psyche, in order to protect you from these memories and in order to protect you from losing your humanity, erases certain memories that are too painful to deal with, that are too overwhelming to deal with. And whether it is to punish the men in your squad or the men in your unit or to erase the face of a child whose father was decapitated next to him in a car at a traffic control point, or whether it is to pose next to a dead civilian or Iraqi or whoever, it is necessary to become dehumanized, because war is dehumanizing.

And we have a whole new generation—we have over a million Iraqi dead. We have over five million Iraqis displaced. We have close to 4,000 dead. We have close to 60,000 injured, both by combat injuries and non- combat injuries, coming back from this war. That’s not even counting the post-traumatic stress disorder and all the other psychological and emotional scars that our generation is bringing home with them. So all that just to say that war is dehumanizing a whole new generation of this country and destroying the people in the country of Iraq. In order for us to reclaim our humanity as a military and as a country, we demand the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of all troops from Iraq, care and benefits for all veterans, and reparations for the Iraqi people so they can rebuild their country on their terms.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejia served six months in Iraq in 2003 with the Florida Army National Guard. After a brief leave, he refused to return. He was court-martialed and served nearly a year in prison. He’s now the chair of the board of Iraq Veterans Against the War, the organization that sponsored the Winter Soldier hearings.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return, on this fifth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq, to Winter Soldier, Iraq and Afghanistan eyewitness accounts of the wars and occupations.

MIKE TOTTEN: […] Mike Totten, I served with the 716th MP Battalion in the 101st Airborne. I was deployed to Iraq in April of 2003 and returned home in April of 2004. For the first six months of my deployment, I served as a driver for a security vehicle for my command sergeant major and my lieutenant colonel. And for the last six months I served, I was put back in a line platoon with the 194th MP Company. Our mission was in part to run a jail in Karbala, not for enemy prisoners of war, but just for the general population prison. These prisoners would be brought into the—by the Iraqi police, and then we were to show them through the processing and how we do things in America.

We weren’t in charge necessarily of any prisoners of war, but on the night of October 17th in 2003, six people were brought in by the Iraqi police, who claimed that these six were participants in the actions the night prior, therefore they were enemy prisoners of war due to coalition standards. When these people were brought in, they were—appeared to be beaten already badly. They were lined up on the concrete wall, and they interlaced—they were—we were told—we told them to interlace their fingers, which is a form of control, because you can grab your middle finger and your index finger and squeeze them together, and it’s quite painful—interlace their fingers, place their foreheads on the concrete wall, cross your ankles, put your hands on top of your head, so we can search you and process you in. They were tagged, they were searched, and they were also beaten, not just by Americans, but by Bulgarian soldiers and by Polish soldiers, by Iraqi policemen and by me.

I grabbed a man by the jaw, and I looked him in the eye, and I slammed his head up against the wall. And I looked him again in the eye and said, "You must have been the one that killed Grilley." And then he fell. I kicked him. An Iraqi policeman, probably the size of the biggest security man here, with hands to match the size of a Kodiak, hit a guy in the side of the head about six times, and I thought to myself—I’m looking at him, and I laughed—I’m like, yeah, these guys are getting what they deserve. I never found out whether or not—this all took place also in the presence of a lieutenant, my lieutenant, within earshot of many NCOs—I never found out what happened to these people, these six prisoners. I don’t know whether they—where they went. I don’t know anything about that. And I’m up here today to speak on behalf of all the people who haven’t returned home, who can’t speak. This isn’t just some isolated incident. This happened in the presence of NCOs, commissioned officers and coalition forces, not only as participants, but also as witnesses.

From the night before October 16th—or October 17th, the night of October 16th, my lieutenant colonel was also killed that night. My being up here displays my anger, both by—on multiple levels: by the Americans’ behavior overseas, by our presidents continuous rhetoric about Iraq being a success, about this country’s citizens—an apathy to this occupation. And this is why I’m here today, as well. These events happen in our name, and each and every single one of you are responsible for this, as well. I am very sorry for my actions, and I can’t take back what I did. I ask the forgiveness of the people of Iraq and of my country, and I will not enable this any further.

General Petraeus, you may not remember me, but you once led me. You’re no longer a leader of men. You’ve exploited your troops for your own gain and have become just another cheerleader for this occupation policy that is destroying America. General Petraeus, you pinned this on me in Babylon in 2003 following the October 16th incident. I will no longer be a puppet for your personal gain and for your political career.

AMY GOODMAN: Former US Army Specialist Mike Totten ripping up the medal General Petraeus had pinned on him in Iraq. He served with the 716th MP Battalion in the 101st Airborne and was deployed to Iraq in April 2003 ’til April 2004. As we turn now to the Luceys, a mother and father who lost their son, not in Iraq, but after he returned home.

JOYCE LUCEY: My name is Joyce Lucey, and I’m the mom of Corporal Jeffrey Michael Lucey. The last month of his life, he had this flashlight by his bedside, and he was looking for the camel spiders that he could hear running around the room. And when he went over to Iraq, he asked me to hold this coin for him every day, so he’d come home safely. I had no idea that it was after he came home that I should have been holding this coin.

Jeffrey’s death should never have happened. The young man, who in January of 2003 was sent to Kuwait to participate in an invasion in which he did not agree, was not the same young man that stepped off the bus in July. Our Marine physically returned to us, but his spirit died somewhere in Iraq. As we celebrated his homecoming, Jeff masked the anger, the guilt, the confusion, pain and darkness that are part of the hidden wounds of war behind his smile.

Jeff was in Kuwait with the 6th Motor Transportation Battalion. He was a convoy driver. On the 20th of March, he entered in his journal, which I have here, "At 10:30 p.m., a scud landed in our vicinity. We were just falling asleep when a shockwave rattled through our tent. The noise was just short of blowing out your eardrums. Everyone’s heart truly skipped a beat, and the reality of where we are and what’s happening hit home." The last entry is, "We now just had a gas alert, and it’s past midnight. We will not sleep. Nerves are on edge." The invasion had begun, and Jeff never had time to put another entry in.

Several months after his return, he said that he would like to complete it. We never knew that he did not—he would never get the time to do that. Our fear the whole time he was over there was that he would be physically harmed. We never imagined that an emotional wound could and would be just as lethal.

The letters we received from him were brief and sanitized. But to his girlfriend of six years, he said in April of 2003 he felt he had done immoral things and that he wanted to erase the last month of his life. "There are things I wouldn’t want to tell you or my parents, because I don’t want you to be worried. Even if I did tell you, you’d probably think I was just exaggerating. I would never want to fight in a war again. I’ve seen and done enough horrible things to last me a lifetime." This is the baggage that my son carried with him when he stepped off that bus that sunny July day at Fort Nathan Hale, New Haven, Connecticut.

Over the next several months, we missed the signs that Jeffrey was in trouble. We had no way of knowing that during his post-deployment briefing at Camp Pendleton he was told to watch the direction that he was going in his survey, or else he’d be kept there another two to four months. He was careful from then on.

In July, he went to the Cape with his girlfriend, and she found him rather distant. He didn’t want to walk the beach. He later told a friend at college that he had seen enough sand to last him a lifetime. At his sister’s wedding in August, he told his grandmother, "You could be in a room full of people, but you could feel so alone." He resumed college in 2003. That fall, we found out that Jeff had been vomiting just about every day since his return, and that kind of kept up right until the day he died.

On Christmas Eve, his sister came home early to see how he was doing. He had been drinking. He was standing by the refrigerator, and he grabbed his dog tags and he tossed them to her, and he called himself a murderer. We were to find out that these dog tags included two Iraqi soldiers that he feels—or he knows he’s personally responsible for their deaths. His private therapist, who saw him the last seven weeks of his life, said he didn’t wear them as a trophy, but he wore them to honor these men. He had a nightmare in February. He told me he was having a dream that they were coming after him in an alleyway. After his death, we kind of checked the VA records, and he had talked to them also about having nightmares in which he was running from alleyway to alleyway.

Spring break 2004 began, three months in which our family watched the son and brother we knew fall apart. He was depressed and drinking. When college classes resumed, he found attending classes very difficult. He had panic attacks, feeling that the other students were staring at him, even though he realized they weren’t. He was placed on Klonopin and Prozac to see if it could keep him in class. Jeff’s problems just worsened. He was having trouble sleeping, nightmares, poor appetite, isolating himself in his room. He was unable to focus on studies, so he could take his—so he could not take his finals. An excellent athlete, his balance was badly compromised by the mixture of Klonopin and alcohol.

He confided in his younger sister that he had a rope and a tree picked out near the brook behind our home, but told her, "Don’t worry. I’d never do that. I wouldn’t hurt Mom and Dad." He was adamant that the Marines not be told, fearing a Section 8 and not wanting the stigma that is connected to PTSD to follow him throughout his life.

He finally went to the VA, after being assured that they were not part of the military and would not relay any information without Jeff’s permission. His dad called and explained what was happening with our son, and they said it was classic PTSD and that he should come in as soon as possible. The problem was getting Jeffrey to actually go in. It was—he kind of—every day it was "Tomorrow. I’ll go in tomorrow. I’m tired." He just didn’t have the energy to get up. The day he went in, he blew up .328, and it was decided he needed to stay. As it was decided he needed to stay, it took six employees to take Jeffrey down. He had gotten out the door and ran out into the parking area.

Involuntarily committed for four days, the stay did nothing but make him feel like he was being warehoused. After seeing an admitting psychiatrist, he would not see another one until the day of his discharge. After answering in the affirmative that he was thinking of harming himself and revealing the three methods—overdose, suffocation or hanging—he was released on June 1st, 2003, a Tuesday. We found out later that he told them on Friday, the day that he was admitted, that he had a hose to choke himself. None of this was ever relayed to us.

They told us while he was there that he would not be assessed for PTSD until he was alcohol-free. But Jeffrey was using this alcohol as self-medication, and he had told us often that’s the only way he could sleep at night. That we might—and the VA said that we might have to consider kicking him out of the house so he would hit rock bottom and then realize he needed his help. That wasn’t an option for us.

On his discharge interview, Jeff said there were three phone calls that the psychiatrist took, one of them being just before he was going to tell her about the bumps in the road, the children they were told not to stop their vehicles for and just not to look back. He decided not to, after she took the call, feeling she wasn’t really interested.

On June 3rd, on a Dunkin’ Donut run—and this was two days after he was released from the hospital—he totaled our car. Was it a suicide attempt? We’re never going to know. No drinking was involved. I was terrified I was losing my little boy. I asked him where he was. He touched his chest, and he said, "Right here, Mom."

On the 5th, he arrived at HCC, Holyoke Community College, where he was a student. But because of not taking the finals, he would not be graduating. But he arrived there to watch the graduation of his sister. This was supposed to be his graduation also. How he drove his car there, we’ll never know. He was so impaired. We managed to get him home, but his behavior got worse. He was very depressed.

My parents, who saw their grandson often, never saw him like this. His sisters and brother-in-law and my dad took him back to the VA. He did not want my husband to go, because he felt he was going to be involuntarily committed again. They were waiting for him, but he refused to go in the building. He was intelligent, didn’t want to get committed again like the weekend before. They decided, without consulting someone with the authority to commit him involuntarily, that he was neither suicidal or homicidal, there was nothing they could do. Our daughters called home in a panic saying it didn’t look like they were going to keep their brother. In their records, they say the grandfather pleaded for someone to help his grandson. Neither our veterans nor their families should ever have to beg for the care they should be entitled to.

My father lost his only brother in World War II. He was twenty-two years old. He was now watching his only grandson self-destructing at twenty-three because of another war.

Kevin and I went through the rooms when we knew Jeff was coming back. We took his knives, bottles, anything we felt he could harm himself with, a dog leash. I took a stepstool, anything that I thought could trigger something in his mind. His car was disabled not only to protect himself, but to protect others from Jeffrey. Kevin called the civilian authorities. They said they can’t—"We can’t touch him. He’s drinking." My child was struggling to survive, and we didn’t know who to turn to. There was no follow-up call from the VA, no outreach, though they knew he was in crisis. We had no guidance—what to say to him, how to handle his situation. You hear a lot about supporting our troops, but I’ll tell you: we felt isolated, abandoned and alone.

While the rest of the country lived on, going to Disney World, shopping, living their daily lives, our days consisted of constant fear, apprehension, helplessness, while we watched this young man being consumed by this cancer that ravaged his soul. I sat on the deck with this person who was impersonating my son and listened to him while he recounted bits and pieces of his time in Iraq. Then he would grind his fist into his hand, and he’d say, "You could never understand."

On Friday, June 11th, around midnight, my daughter got a call from a girl down the street. She asked me, "Where’s your son?" And I said, "Debs, he’s in his room. He’s sleeping." Well, apparently not. He had climbed out the window and gotten into this girl’s car. He wanted some beer. She was—this girl who had known Jeffrey all her life was a little bit scared of him. When I saw him get out of the car, I froze. Jeff was in—dressed in his cammies with two k-bars, a modified pellet gun, which the police wouldn’t know, and carrying a six-pack. He had just wanted that beer. There was a sad smile on his face like a lost soul. When I told him how concerned I was about him, he said, "Don’t worry, Mom. No matter what I do, I always come back."

KEVIN LUCEY: So later that evening, we had decided that we were going to try to go out, because he had become reclusive in the house. We were going to try to go out for a steak dinner the following night. At about 11:30, quarter to 12:00, Jeffrey asked me, for the second time within the past ten days, if he could just sit in my lap and I could rock him for about—well, for a while. And we did. We sat there for about forty-five minutes, and I was rocking Jeff, and we were in total silence. As his private therapist that we had hired said, it was his last harbor and his last place of refuge.

The next day, I came home. It was about quarter after 7:00. I held Jeff one last time, as I lowered his body from the rafters and took the hose from around his neck.

AMY GOODMAN: Kevin and Joyce Lucey, their son, Marine Lance Corporal Jeffrey Lucey, served five months in Iraq in 2003 with the 6th Motor Transport Battalion. Almost a year later, he committed suicide, June 22nd, 2004. He was twenty-three years old. We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: On this fifth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq, we return to the testimony of soldiers this past weekend speaking about the horrors of war. This is Winter Soldier.

TANYA AUSTIN: […] Tanya Austin, and I am a US Army veteran, but I am not here speaking on—about my own story today. I am actually here to give a story of an incredibly strong and brave individual. This is a story of a female in the Coast Guard who was raped and then discharged and punished for being raped. I’m—I’ve been lucky enough to meet this young woman and see the amazing things she has done to bring not only her story out, but the story of men and women who have been raped in the military.

If you guys could throw up the website, please? What we have up here is stopmilitaryrape.com—or dot-org, sorry. And what’s really cool about this website is it was this individual’s way of telling her story and trying to make progress, because the military didn’t do anything to help her. So, finally, she decided, well, if the military won’t help me, I’m going to help me and everyone like me.

As you see there on the homepage, these are some really frightening statistics. 25 percent of women will be sexually assaulted on college campuses. 12 percent of women will be raped while in college. 28 to 66 percent of women in the military report sexual assault. The reason the number varies so much is military reports versus VA reports. It’s a lot easier to tell someone at the VA that you’ve been sexually assaulted than it is to tell your own command, which is not right. And 27 percent of women are reported raped. And what’s interesting about this statistic is if you report that you’ve been raped and no charges are brought against your rapist, you haven’t been raped. You’re not part of that statistic. And, unfortunately, for our military, this is something that happens way too often, is the cover-up of sexual assault, of rape of individuals experiencing the worst from their comrades.

So here is what they’re currently doing about it. According to the Department of Defense’s own statistics, 74 to 85 percent of soldiers convicted of rape or sexual assault leave the military with an honorable discharge, meaning rape conviction does not appear in their records anywhere. Only two to three percent of soldiers accused of rape are ever court-martialed. And only five to six percent of soldiers accused of domestic abuse are ever court-martialed. In fact, several multiple homicides have recently taken place on military bases that have not even been criminally prosecuted. The Department of Defense’s definition of morale booster for male soldiers: female soldiers—take as needed, dispose when finished and continue serving with honor. Please remember that many suffer in silent shame and never forget what’s going on.

Now I’d like to tell this individual’s particular story. And having experienced sexual harassment in the military myself, this is kind of difficult, as it is for everyone on this panel up here. But our stories need to be told.

We are often asked how we get started with Stop Military Rape, Military Rape Crisis Center. I’m a veteran of the United States Coast Guard and a survivor of military sexual trauma. I was raped in May of 2006 by a fellow shipmate. I followed all the necessary steps, including reporting the assault and providing evidence: a confession letter written by my rapist. In August of 2006, I was informed that I will be discharged. According to the Coast Guard Academy psychologist, surviving rape makes deployment—makes one ineligible for worldwide deployment, and as a result, I can no longer serve in the Coast Guard. What follows was a nine-month battle between the Coast Guard and myself, while I tried to keep my job and change the Coast Guard’s unofficial policy that rape survivors shouldn’t be allowed to serve in the Coast Guard.

I was a female in my early twenties, brand new to the Coast Guard. I admit it: I did not know every Coast Guard policy or try to know something beyond my E3 rank. All I know is that what was happening to me was not—was just not right. I felt powerless. I didn’t know how to fight the military. I was taught how to fight with them, for them. But how could I fight for my rights to stay with them?

Out of the need to vent and needing an outlet to express the horror I was experiencing as a result of being raped, I started an online blog on MySpace. I was not expecting much of it. I just wanted to let out all the pain in me and share with the public. I almost immediately started receiving emails from active-duty military members and veterans alike, each wanting to share their story. Everybody’s story was so different, yet so similar. I received one email from an eighteen-year-old female who was raped two hours prior by a member of her command and was scared and had no one else to turn to. I received an email from a Coast Guard veteran who was raped ten-plus years ago while serving, and I was the first person he ever told.

I started doing research online about military rape. I learned about Tailhook and read the brave story of Army Specialist Suzanne Swift. What was happening to me in the Coast Guard was very common and had been going on for a long time. I knew that I was in for the biggest battle of my life. I could not abandon my fellow men and women in uniform. Something’s got to change.

Stop Military Rape and the Military Rape Crisis Center was formed. We are the nation’s largest support group for the survivors of military sexual trauma. In 2007, we assisted over 12,000 men and women of military sexual trauma and their families. We are starting to work with Congress to change the military policy of sexual assault. Every man and woman that volunteer to serve their country should have the right to serve without the fear of being sexually assaulted, harassed and/or raped. In addition, no one should be reprimanded or punished for reporting a crime that was done to them.

May 30th is International Stop Military Rape Awareness Day. Write to your representatives, contact the media, do what we’re doing now, and let them know that military rape is something we just can’t stand for.

This young woman is remarkable, her story, powerful. And unfortunately, because of time, we can’t tell her whole story. But every person up here has a story to tell. Every veteran out there, every active-duty member that’s sitting in this audience knows someone that has either been assaulted or raped or harassed. And that has got to change.

AMY GOODMAN: Tanya Austin was an Arab linguist in Military Intelligence, testifying at Winter Soldier in Silver Spring this weekend. It’s the largest gathering of active-duty and Iraq and Afghanistan war vets. We continue with Winter Soldier.

JEFFREY SMITH: My name is Jeffrey Smith. I enlisted in the Army as an infantryman in September 1997. I served three years active-duty in the 3rd Infantry Division and then enlisted for six further years in the Florida National Guard. I was a grenadier with Bravo Company, 2nd of the 124th Infantry, and was deployed to Camp Anaconda, Balad, Iraq, in early May 2003. I was honorably discharged in January 2004.

I reside in Orlando, Florida, and was raised as a military brat. My father served two tours in Vietnam and is currently rated 100 percent disabled by the Veterans Administration due to PTSD and Agent Orange exposure.

Upon deployment to Balad, my unit was primarily tasked with gate and perimeter security at Camp Anaconda, the largest of the enduring presence bases in Iraq. Providing security at the front gate, one of the daily rituals we were tasked with was clearing Iraqi nationals who came to work on a daily basis on post, doing such jobs as filling sandbags, clearing rubble and trash, etc. These Iraqi nationals were paid a dollar a day and were given an MRE for lunch. They worked under extreme conditions of heat and dust, oftentimes 130-degree temperature, and were always escorted by armed guards.

One of the other missions that we were occasionally tasked with was raiding houses in the local area, especially when we first arrived in country. One of the houses that we first raided was supposedly the home of a former Baath official. It was the middle of the day when we raided this house. When we arrived in the neighborhood, we were told that we were going to try to force the front gate open to the house, but apparently the armored cavalry unit that was with us had other plans in mind. They rolled over the front wall of the house, destroyed the vehicle that was inside, and upon entry to the house, I was second in the stack of a formation of troops that went through the gate. There was an older female who was in the courtyard by this time, and she was screaming something unintelligible in Arabic. I didn’t see her as a threat, so I continued on past her into the building itself. One of the soldiers behind me apparently thought that she was a threat, butt-stroked her in the face, knocked her to the ground, and someone after him apparently zip-tied her and took her out into the front yard.

Then we proceeded to ransack this house. I was in the master bedroom. There was dressers and wardrobes. Wardrobes were locked. We pulled the doors off. We turned everything in the room upside-down. We went through everything. Personnel in my unit that were in the kitchen turned the refrigerator upside-down, pulled the stove—actually broke the stove, pulled it out of the wall, broke the line to it.

After we searched through the house and we had everyone, including the children, zip-tied on the front lawn, apparently someone in my chain of command realized that we had the wrong home, we were on the wrong street, that the home we were supposed to have raided was actually behind this house on another street. So we went over to that home and raided that house. Actually, going through that gate of that home, I actually almost fired on a person that I believe was mentally disabled. He apparently—he didn’t understand what was going on. He was standing in a window directly in front of us, and in the initial first few seconds of going through the wall, I actually thought that he was a threat, almost fired, and then realized that there was something wrong with him and he just didn’t realize what was happening.

We searched through that home, detained the person that we were supposed to detain. And, you know, upon searching the home, we started coming across all this paperwork in his office and in his bedroom, and it looked to me like he was an algebra instructor, maybe at the local high school, maybe at a local university, because there was just reams of stuff that was math problems. This guy is supposed to be a former Baath official.

We took him, put a sandbag over his head, loaded him on a truck, and we started back towards Camp Anaconda. He was actually on my vehicle with my squad, and on the way back to Camp Anaconda—it was about a forty-five-minute drive—my squad leader thought that it would be funny to pose for a picture next to this guy, and he asked me to take a photo of him and this detainee. And I refused to do so. I didn’t believe that that was the right thing to do. And upon arrival back at our quarters, I was disciplined for quite some time for this, including physical punishment, because I had disobeyed him in front of the rest of the squad.

Really, the turning point for me on my experience in Iraq was an incident that occurred when I was off duty at night. There was a platoon in my company who were—how shall I put this? They were the hardcore platoon. You know, every unit has one platoon that is more extreme than the rest. This platoon happened to have a squad that was on—well, they called it an ambush, but really what it was is they were hiding out in the farms in the surrounding area outside the perimeter, and they were trying to detain and stop people who were out past curfew. So they were out there one night, and apparently a farmer was on his property—I think it was about 3:00 in the morning—and, you know, electricity was intermittent, and he was out there, I think, trying to work on his farm, work on a pump or something. They told him to halt and stop. He panicked and ran. They opened fire, and they killed this individual.

The next day, Civil Affairs came and spoke with us and said—as a company—and said, "We are not going to pay any benefit to this family." They also informed us that his brother was a close ally of us, who was work-–had up until this time had been working with us and was a respected leader of the local community and that this individual that we killed also had fourteen children. The Civil Affairs officer suggested that we take up a collection and donate a dollar or two apiece to the family, and that he thought that that would go a long way in helping to ease the family’s suffering. There’s 125 members of a rifle company, roughly, so you’re talking about anywhere probably between $125 and $150. In reality, I don’t think anyone donated any money.

And finally, just to wrap things up, I want to take this time to apologize to the Iraqi people for the things that, you know, I helped to do, and the actions that people in my unit and myself did while I was there. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Jeffrey Smith, an infantryman for six years, served in Iraq in May 2003, honorably discharged January 2004, testifying at Winter Soldier in Silver Spring, an echo of an earlier gathering in Detroit, Michigan in 1971, when Vietnam vets spoke about their experiences there. 200 years earlier, in the winter of 1776, Thomas Paine wrote, "These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of [their] country; but he that stands [by] it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman." Referencing Thomas Paine, the soldiers testifying about the horrors of war two centuries later called themselves "Winter Soldier." Today, five years after the invasion began, nearly 160,000 troops remain stationed in Iraq, close to 4,000 have died. The number of Iraqis dead is still unknown. It could be more than a million.