Thursday, July 31, 2008

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

If socialism fails: the spectre of 21st century barbarism

By Ian AngusJuly 27, 2008

From the first day it appeared online, Climate and Capitalism’s masthead has carried the slogan “Ecosocialism or Barbarism: there is no third way.” We’ve been quite clear that ecosocialism is not a new theory or brand of socialism — it is socialism with Marx’s important insights on ecology restored, socialism committed to the fight against ecological destruction. But why do we say that the alternative to ecosocialism is barbarism?

Marxists have used the word “barbarism” in various ways, but most often to describe actions or social conditions that are grossly inhumane, brutal, and violent. It is not a word we use lightly, because it implies not just bad behaviour but violations of the most important norms of human solidarity and civilised life. [1]

The slogan “Socialism or Barbarism” originated with the great German revolutionary socialist leader Rosa Luxemburg, who repeatedly raised it during World War I. It was a profound concept, one that has become ever more relevant as the years have passed.

Rosa Luxemburg spent her entire adult life organising and educating the working class to fight for socialism. She was convinced that if socialism didn’t triumph, capitalism would become ever more barbaric, wiping out centuries of gains in civilisation. In a major 1915 antiwar polemic, she referred to Friedrich Engels’ view that society must advance to socialism or revert to barbarism and then asked, “What does a ‘reversion to barbarism’ mean at the present stage of European civilisation?”

She gave two related answers.

In the long run, she said, a continuation of capitalism would lead to the literal collapse of civilised society and the coming of a new Dark Age, similar to Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire: “The collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration — a great cemetery.” (The Junius Pamphlet) [2]

By saying this, Rosa Luxemburg was reminding the revolutionary left that socialism is not inevitable, that if the socialist movement failed, capitalism might destroy modern civilisation, leaving behind a much poorer and much harsher world. That wasn’t a new concept – it has been part of Marxist thought from its very beginning. In 1848, in The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote:

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles … that each time ended, either in the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.”

In Luxemburg’s words: “Humanity is facing the alternative: Dissolution and downfall in capitalist anarchy, or regeneration through the social revolution.” (A Call to the Workers of the World)

Capitalism’s two faces

But Luxemburg, again following the example of Marx and Engels, also used the term “barbarism” another way, to contrast capitalism’s loudly proclaimed noble ideals with its actual practice of torture, starvation, murder and war.

Marx many times described the two-sided nature of capitalist “progress”. In 1853, writing about British rule in India, he described the “profound hypocrisy and inherent barbarism of bourgeois civilisation [that] lies unveiled before our eyes, turning from its home, where it assumes respectable forms, to the colonies, where it goes naked.”

Capitalist progress, he said, resembled a “hideous, pagan idol, who would not drink the nectar but from the skulls of the slain.” (The Future Results of British Rule in India)

Similarly, in a speech to radical workers in London in 1856, he said:

“On the one hand, there have started into life industrial and scientific forces, which no epoch of the former human history had ever suspected. On the other hand, there exist symptoms of decay, far surpassing the horrors recorded of the latter times of the Roman Empire.” (Speech at the Anniversary of the People’s Paper)

Immense improvements to the human condition have been made under capitalism — in health, culture, philosophy, literature, music and more. But capitalism has also led to starvation, destitution, mass violence, torture and even genocide — all on an unprecedented scale. As capitalism has expanded and aged, the barbarous side of its nature has come ever more to the fore.

Bourgeois society, which came to power promising equality, democracy and human rights, has never had any compunction about throwing those ideals overboard to expand and protect its wealth and profits. That’s the view of barbarism that Rosa Luxemburg was primarily concerned about during World War I. She wrote:

“Shamed, dishonoured, wading in blood and dripping in filth, this capitalist society stands. Not as we usually see it, playing the roles of peace and righteousness, of order, of philosophy, of ethics — as a roaring beast, as an orgy of anarchy, as pestilential breath, devastating culture and humanity — so it appears in all its hideous nakedness …

“A look around us at this moment shows what the regression of bourgeois society into barbarism means. This world war is a regression into barbarism.” (The Junius Pamphlet)

For Luxemburg, barbarism wasn’t a future possibility. It was the present reality of imperialism, a reality that was destined to get much worse if socialism failed to stop it. Tragically, she was proven correct. The defeat of the German revolutions of 1917 to 1923, coupled with the isolation and degeneration of the Russian Revolution, opened the way to a century of genocide and constant war.

In 1933, Leon Trotsky described the rise of fascism as “capitalist society … puking up undigested barbarism”. (What is National Socialism?)

Later he wrote: “The delay of the socialist revolution engenders the indubitable phenomena of barbarism — chronic unemployment, pauperization of the petty bourgeoisie, fascism, finally wars of extermination which do not open up any new road.” (In Defense of Marxism)

More than 250 million people, most of them civilians, were killed in the wars of extermination and mass atrocities of the 20th Century. This century continues that record: in less than eight years over three million people have died in wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere in the Third World, and at least 700,000 have died in “natural” disasters.

As Luxemburg and Trotsky warned, barbarism is already upon us. Only mass action can stop barbarism from advancing, and only socialism can definitively defeat it. Their call to action is even more important today, when capitalism has added massive ecological destruction, primarily affecting the poor, to the wars and other horrors of the 20th century.

21st century barbarism

That view has been expressed repeatedly and forcefully by Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez. Speaking in Vienna in May 2006, he referred explicitly to Luxemburg’s words:

“The choice before humanity is socialism or barbarism. … When Rosa Luxemburg made this statement, she was speaking of a relatively distant future. But now the situation of the world is so bad that the threat to the human race is not in the future, but now.” [3]

A few months earlier, in Caracas, he argued that capitalism’s destruction of the environment gives particular urgency to the fight against barbarism today:

“I was remembering Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg and the phrase that each one of them, in their particular time and context put forward; the dilemma ‘socialism or barbarism.’ …

“I believe it is time that we take up with courage and clarity a political, social, collective and ideological offensive across the world — a real offensive that permits us to move progressively, over the next years, the next decades, leaving behind the perverse, destructive, destroyer, capitalist model and go forward in constructing the socialist model to avoid barbarism and beyond that the annihilation of life on this planet.

“I believe this idea has a strong connection with reality. I don’t think we have much time. Fidel Castro said in one of his speeches I read not so long ago, “tomorrow could be too late, let’s do now what we need to do.” I don’t believe that this is an exaggeration. The environment is suffering damage that could be irreversible — global warming, the greenhouse effect, the melting of the polar ice caps, the rising sea level, hurricanes — with terrible social occurrences that will shake life on this planet.” [4]

Chavez and the revolutionary Bolivarian movement in Venezuela have proudly raised the banner of “21st Century Socialism” to describe their goals. As these comments show, they are also raising a warning flag, that the alternative to socialism is 21st century barbarism — the barbarism of the previous century amplified and intensified by ecological crisis.

Climate change and ‘barbarisation’

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been studying and reporting on climate change for two decades. Recently the vice-chair of the IPCC, Professor Mohan Munasinghe, gave a lecture at Cambridge University that described “a dystopic possible future world in which social problems are made much worse by the environmental consequences of rising greenhouse gas emissions.”

He said: “Climate change is, or could be, the additional factor which will exacerbate the existing problems of poverty, environmental degradation, social polarisation and terrorism and it could lead to a very chaotic situation.”

“Barbarisation”, Munasinghe said, is already underway. We face “a situation where the rich live in enclaves, protected, and the poor live outside in unsustainable conditions.” [5]

A common criticism of the IPCC is that its reports are too conservative, that it understates how fast climate change is occurring and how disastrous the effects may be. So when the vice-chair of the IPCC says that “barbarisation” is already happening, no one should suggest that it’s an exaggeration.

The present reality of barbarism

The idea of 21st century barbarism may seem farfetched. Even with food and fuel inflation, growing unemployment and housing crises, many working people in the advanced capitalist countries still enjoy a considerable degree of comfort and security.

But outside the protected enclaves of the global north, the reality of “barbarisation” is all too evident.

- 2.5 billion people, nearly half of the world’s population, survive on less than two dollars a day.

- Over 850 million people are chronically undernourished and three times that many frequently go hungry.

- Every hour of every day, 180 children die of hunger and 1200 die of preventable diseases.

- Over half a million women die every year from complications of pregnancy and childbirth. 99% of them are in the global south.

- Over a billion people live in vast urban slums, without sanitation, sufficient living space, or durable housing.

- 1.3 billion people have no safe water. 3 million die of water-related diseases every year.

The United Nations Human Development Report 2007-2008 warns that unmitigated climate change will lock the world’s poorest countries and their poorest citizens in a downward spiral, leaving hundreds of millions facing malnutrition, water scarcity, ecological threats and a loss of livelihoods. [6]

In UNDP Administrator Kemal Dervi’s words: “Ultimately, climate change is a threat to humanity as a whole. But it is the poor, a constituency with no responsibility for the ecological debt we are running up, who face the immediate and most severe human costs.” [7]

Among the 21st century threats identified by the Human Development Report:

- The breakdown of agricultural systems as a result of increased exposure to drought, rising temperatures, and more erratic rainfall, leaving up to 600 million more people facing malnutrition.

- An additional 1.8 billion people facing water stress by 2080, with large areas of South Asia and northern China facing a grave ecological crisis as a result of glacial retreat and changed rainfall patterns.

- Displacement through flooding and tropical storm activity of up to 332 million people in coastal and low-lying areas. Over 70 million Bangladeshis, 22 million Vietnamese, and six million Egyptians could be affected by global warming-related flooding.

- Expanding health risks, including up to 400 million more people facing the risk of malaria.

To these we can add the certainty that at least 100 million people will be added to the ranks of the permanently hungry this year as a result of food price inflation.

In the UN report, former South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu echoes Munasinghe’s prediction of protected enclaves for the rich within a world of ecological destruction:

“While the citizens of the rich world are protected from harm, the poor, the vulnerable and the hungry are exposed to the harsh reality of climate change in their everyday lives…. We are drifting into a world of ‘adaptation apartheid’.”

As capitalism continues with business as usual, climate change is fast expanding the gap between rich and poor between and within nations, and imposing unparalleled suffering on those least able to protect themselves. That is the reality of 21st century barbarism.

No society that permits that to happen can be called civilized. No social order that causes it to happen deserves to survive.

* * *

Ian Angus is editor of the online journal Climate and Capitalism and an associate editor of Socialist Voice.

Footnotes

[1] In “Empire of Barbarism” (Monthly Review, December 2004), John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark provide an excellent account of the evolution of the word “barbarism” and its present-day implications.

The best discussion of Rosa Luxemburg’s use of the word is in Norman Geras, The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg (NLB 1976), which unfortunately is out of print.

[2] The works of Marx, Engels, Luxemburg and Trotsky that are quoted in this article can be found online in the Marxists Internet Archive.

[3] Hands Off Venezuela, May 13, 2006.

[4] Green Left Weekly, August 31, 2005.

[5] “Expert warns climate change will lead to ‘barbarisation’” Guardian, May 15, 2008.

[6] United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2007/2008.

[7] “Climate change threatens unprecedented human development reversals.” UNDP News Release, Nov. 27, 2007.

Socialist Voice is a forum for discussion of today’s struggles of the workers and oppressed from the standpoint of revolutionary Marxism. Readers are encouraged to distribute Socialist Voice as widely as possible.

Al-Qaeda's got a brand new bag

THE ROVING EYE

Al-Qaeda's got a brand new bag

By Pepe Escobar

(View Original)

WASHINGTON - Al-Qaeda is back - with a vengeance of sorts. Listen to Mustafa Abu al-Yazeed - a senior al-Qaeda commander in Afghanistan, in a very rare interview with Pakistan's Geo TV, shot in Khost, in eastern Afghanistan.

"At this stage this is our understanding - that there is no difference between the American people and the American government itself. If we see this through sharia [Islamic] law, American people and the government itself are infidels and are fighting against Islam. We have to rely on suicide attacks which are absolutely correct according to Islamic law. We have adopted this way of war because there is a huge difference between our material resources and our enemy's, and this is the only option to attack our enemy."

The interview is not only about defensive jihad. Yazeed delves into classic al-Qaeda strategy - inciting a cross-border Taliban jihad against the US and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces and blasting a state, in this case the government of Pakistan. According to him, "Sadly, it is the government of Pakistan which has most damaged our cause. President [Pervez] Musharraf violated the trust of Muslims and contributed to the destruction of the Islamic government of Afghanistan ... Musharraf and his government have made big mistakes, there is no such example in other Islamic states."

Yazeed also said al-Qaeda was responsible for the suicide car bombing on the Danish Embassy in Islamabad in early June, when six people were killed.

So why is al-Qaeda feeling so emboldened to have one of its top commanders on camera - and on a foreign TV network to boot, not as-Sahab, al-Qaeda's media arm?

I want my emirate

Jihadis now assess that the new Afghan jihad - against the "infidel" US and NATO troops combined - is more important at the moment than Iraq. So in this sense, Democratic presidential candidate Senator Barack Obama has got it right - Afghanistan, and not Iraq, is "the central front in the war on terror".

But it's much more complicated than that. The central front is actually in Pakistan. Al-Qaeda basically wants a pan-Islamic caliphate. The neo-Taliban, based in Pakistan, are not that ambitious. They already have their Islamic Emirate - it is in the Waziristan tribal areas on the border with Afghanistan. What they want most of all is to expand it. They also know they would never stand a chance of taking over the whole of Pakistan. A Pakistani expert on the tribal areas, currently in Washington, describes it as "a class struggle - almost like an evolving peasant revolution. Baitullah Mehsud [the neo-Pakistani Taliban leader] is but a peasant from a poor family."

What is startling is that the neo-Taliban are now practically in control of North-West Frontier Province on the border with Afghanistan - whose capital is fabled Peshawar. They already control several Peshawar suburbs.

The Pakistani state has virtually no power in these areas. The Taliban enforce strict sharia law. If local security people refuse to obey, they are simply killed. No wonder the neo-Taliban now have subdued scores of middle- and low-ranking Pakistani officials. They even issued a deadline to the new secular and relatively progressive regional government to release all Taliban prisoners - or else. As for the government, the only thing it can do is to organize some sort of neighborhood watch to prevent total Taliban supremacy. This state of affairs also reveals how the Pakistani army seems to be powerless - or unwilling - to fight the Taliban.

Across the border, in Kunar and Nuristan provinces in Afghanistan, the Taliban now control almost all security checkpoints. No wonder Yazeed - speaking for al-Qaeda, envisions a war without borders. He said, in his Geo TV interview, "Yes, we cannot separate the tribal area people from Afghanistan which are part of Pakistan and the Pakistani people. Yes, we are getting support from tribal people in Pakistan, and in fact it is obligatory for them to render this help and it is a responsibility that is imposed by religion. It is not only obligatory for residents of the tribal regions but all of Pakistan."

In a recent high-profile al-Qaeda meeting in Miramshah in North Waziristan, the al-Qaeda leadership made it clear it not only expects - it wants the new Afghan war/jihad to spill over to the tribal areas in Pakistan.

And this is what al-Qaeda will get - according to what Obama told CBS News' Lara Logan, "... what I've said is that if we had actionable intelligence against high-value al-Qaeda targets and the Pakistani government was unwilling to go after those targets, then we should."

The Pentagon for its part is preparing the battlefield - it has already sent Predator drones, repeatedly, over the tribal areas. An air war is in the works - not to mention scores of Pentagon covert special ops.

Al-Qaeda's strategy is to suck in the US military - this is classic Osama bin Laden ideology, according to which the US should be dragged to fight in Muslim lands. Al-Qaeda is reasoning that an attack on the tribal areas, in fact a real third front in the "war on terror" (so dreaded by chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Michael Mullen) will have Pakistani public opinion so outraged that the Pakistani army would be powerless to follow the US track. And al-Qaeda, in the end, would be left with an even freer hand.

Obama and Osama

How does that fabled phantom, bin Laden, fit into this strategy? Is he alive or just ... a phantom? Hassan Ibrahim from al-Jazeera television recently told independent journalist Kristina Borjesson "bin Laden is alive. The kidney failure and dialysis machine stories are nonsense, CIA rumors. In 2002 one of his wives was interviewed for a Saudi magazine and she categorically denied the dialysis story. After Tora Bora [in Afghanistan when the US invaded in 2001], his fourth wife asked for a divorce. He took on a new wife in April 2005, with whom he now has a son. Her father is a powerful Saudi businessman from Hejaz who announced in his mosque that his daughter had married bin Laden."

There's also chatter in the jihadi underground related to an ongoing theological debate with direct participation by bin Laden.

Obama for his part still cannot have grasped the full, complex, picture of what is going on the tribal areas - in his current world tour he's only been to Jalalabad, in eastern Afghanistan, and only for a few hours. But he's on a learning curve - although, for the moment, he seems to be playing to the US military establishment galleries, pledging to add 10,000 US combat troops to the Afghan theater of war. Al-Qaeda will be delighted.

What Obama has certainly accomplished for now is a certified three-pointer - turning George W Bush administration and neo-conservative rhetoric about the "war on terror" in Iraq upside down and applying it to Afghanistan. Obama has been emphasizing the "growing consensus at home that we need more resources in Afghanistan".

In his press conference in Jordan, Obama also emphasized his decision to make Afghanistan the first stop on his world tour because it's the "central front in the war on terror," the place "where 9/11 was planned" and where "terrorists" are "plotting new attacks against the United States".

And here's the clincher - straight out of the neo-con playbook, "We have to succeed in taking the fight to the terrorists." But that's not all. Obama's political jiu-jitsu has mixed this hardcore rhetoric with a global, multilateral vision - not to mention forcing Republicans to accept his own take on the "war on terror". As for the tribal areas, he projects the impression he is allowing himself time to fully understand their complexity.

So what's left to self-described national security expert and Republican presidential candidate Senator John McCain? Well, he did manage to tell ABC's Diane Sawyer the new al-Qaeda and Taliban configuration is "a very hard struggle, particularly giving the situation in the Iraq-Pakistan border".

Pepe Escobar is the author of Globalistan: How the Globalized World is Dissolving into Liquid War (Nimble Books, 2007) and Red Zone Blues: a snapshot of Baghdad during the surge. He may be reached at pepeasia@yahoo.com.

An All-Too-Brief Introduction to Plato

In the realm of Western thought no other philosopher measures up to the contributions of Plato. Contained in his volumes are the building blocks of modernity. Plato’s dialogues meticulously construct a vision of power, the state, justice, social organization and democracy so complete that every other significant political theorist has been required to confront it in order to etch out their own identity. Not everything Plato wrote can be viewed as advisable on a humanitarian level, some of his proposals, such as his Utopia, appear proto-totalitarian in nature. If nothing else, Plato displayed a variety of fearless honesty that set the standard for cultural examination through the ages. Despite his missteps, Plato’s ideas cover much intellectual terrain and still bare relevance today.

It is unclear where Plato was born although it is generally assumed it was near Athens (Diogenes Laertius 3.4). Young Plato received the most rigorous education available to any Greek child. He was taught music, grammar, philosophy and gymnastics as a part of his early schooling. A student of the famous Greek philosopher, Socrates, Plato recorded the words of his teacher in his dialogues, preserving them as Socrates never penned anything himself. The Apology of Socrates noted that Plato was one of Socrates’ most loyal students. As a matter of record, Plato’s name was used against Socrates during his trial as one of the youths he had corrupted. Plato’s admiration for Socrates is evident through the way Plato presents Socrates as an eloquent sage in all of his works. The treatment of Socrates during his trial as well as Socrates’ ideas themselves would shape Plato’s own thought.

In Plato’s most respected work, The Republic, he sets out to assemble the ideal state. The initial question in Plato’s mind is that of justice. Using Socrates as his mouthpiece, Plato enters into a debate to define the nature of justice. A man named Polemarchus suggests justice is merely “giving everyone the good or evil they deserve.” This is to say return right with right and wrong with wrong. Socrates responds by stating that doing harm to others is never warranted. According to Socrates each person exhibits their own category of goodness called “arete”. To do harm to others is unjust as it diminishes this quality. Thrasymachus offers the next stage of Plato’s argument by denying both Polemarchus’ moral reciprocity and Socrates’ arete with a pre-Machiavellian idea of power as a justification for itself. Thrasymachus states “Listen—I say that justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger.” (The Republic, 1.388c). This idea props up the state and its leaders as suspended above the constraints of morality. Socrates refutes Thrasymachus by saying:

“Being a ruler is a craft like being a doctor or a navigator or a wage-labourer. If a man does it, we must pay him, but it is a craft in itself. Men don't want to be called mercenary or over-ambitious, which is why they think it dishonourable to accept command without some pressure and some reluctance; the penalty for refusal being to risk being governed by someone worse than themselves. That is what frightens honest men into accepting power. In a city of good men, there might be as much competition to avoid power as to get it.” (The Republic, 347)

Socrates describes for Thrasymachus the notion of the ruler as physician. It is in a state’s best interest to produce the highest quality citizens, and if each person has his or her own essence which is reduced when harmed then it is not justified for those in power to dilute the arete of those with less authority. In fact, each ruler should have an exceptional knowledge of society and its ailments along with a host of remedies much like a doctor diagnosing a patient. At this point Socrates turns to Glaucon who represents Plato’s third part of his definition of justice. Glaucon agrees with Socrates above Thrasymachus, however, Glaucon poses a dilemma about human nature. Glaucon lays out an thought experiment in which a man finds a ring which can turn him invisible.

“Imagine a just man had such a ring. Would he have such iron will that he could resist taking whatever he wanted? I think not, no man is just of his own will, but only from fear of the law. So much for that, consider how the world views men. The unjust man, if he is skilled, will always appear to be in the right, he'll dishonestly cover up the most monstrous crimes and he'll always have a ready excuse if he's found out. The just man, on the other hand, will act for justice, not just the appearance of justice. And what will happen to him? He'll end up being blamed for others crimes, and like as not scourged and crucified.” (The Republic, 361)

In the eyes of Glaucon human nature displays a fatal flaw -- self-interest. If given unlimited power men would not perform acts of altruism but instead devise ways to feed their avarice. To this Socrates says that Glaucon is only half correct. Each human being has the capacity for limitless greed yet each man and woman is capable of extraordinary compassion. For Socrates the difference between how a population will behave lies in education. People, according to Socrates, need the right type of instruction in order to foster their arete and make just decisions. This reliance on education will be the crux of Plato’s ideal state. Only through proper restraint can the pernicious impulses of people be subverted.

It may be obvious from this view of humanity that Plato did not hold a positive opinion of democracy. He witnessed firsthand, with the execution of Socrates in accord with popular will, what happens when control is handed over to the people. Plato once stated: “Dictatorship naturally arises out of democracy, and the most aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme liberty.” He found democracy promoted “pleasure-seeking” and favored inept rulers. Therefore, his Republic is said to be a reaction against the “anarchy” found inside a democratic state.

The total reconstruction of society needed to occur in three “waves”. The first wave was to give both men and women equal access to power. In ancient Greece women were considered lesser citizens. Plato felt the contributions of women could be valuable and saw the traditional Greek attitude toward women as counterproductive. Plato wanted to build a hierarchy of the best skilled, called a Timocracy, and within this hierarchy women would logically be included. The second wave would abolish private property and the orthodox family of the ruling class. Plato thought leaders in this new society should not be burdened by the distractions of family life therefore he regarded a communal structure to be the most effective arrangement for child-rearing and cementing solid bonds between the members of the elite or “Guardians“. The third and final wave that would transform Plato’s new state is the concept of the philosopher king. In this society only those who can tame their base instincts and nurture their intelligence and arete could rise to the level of a Guardian. The leadership would be required to undergo extensive training and education, demonstrating their superior wisdom (Dennis Dalton, Power Over People: Classical and Modern Political Theory, Lecture 5).

Plato stresses the importance of the role of the philosopher king through the allegory of the cave. Speaking through Socrates, Plato begins:

“I want to go on to picture the enlightenment or ignorance of the human condition as follows: Imagine an underground chamber in which are prisoners who have been chained since childhood with their legs and necks fastened so that they can only look straight ahead. Behind them is a road along which all sorts of men pass behind that a fire so that the prisoners see in front of them the shadows cast by the passers-by and the things they carry.” (The Republic, 515)

To the prisoners in the cave the flickering shadows on the wall is their only reality. It’s not until one of the prisoners breaks his or her chains, finds the surface and returns to inform the others of his or her discovery can the remaining prisoners receive proper guidance. In the allegory, those chained inside the cave represent the majority. They do not question their perception and often become frightened when their assumptions are challenged. The prisoner who journeys to the surface represents the philosopher king. Only someone with exceptional curiosity, aptitude and benevolence is capable of leading those who are unable or unwilling to free themselves. This is the only individual who meets the criteria to helm Plato’s new Republic, a state which will educate, protect and develop every one of its citizens.

To a mind as restless and expansive as Plato’s it is no surprise that he did not limit himself to ideas of social organization. In The Symposium the Greek philosopher focuses on the nature of love. Implementing the same technique found in The Republic, Plato begins the discourse with a dialogue between Socrates and Pausanias. According to Pausanias, love is nothing greater than physical attraction. Aristophanes enters the conversation with his refutation of Pausanias’ proposal.

Aristophanes illustrates his position with a story. There was once a time when both males and females were conjoined into one “third sex”, who didn’t suffer any of the tensions that arise from the friction between the two sexes. Zeus looked down and saw humanity’s bliss and became jealous sending a thunderbolt to tear the human race in two. The feeling of love originates from a yearning to reconnect with the other half of one’s self, not merely physical attraction as Pausanias contended.

Socrates accepted Aristophanes’ definition yet developed it further. In addition, love also pointed to an eternal quality of reality. Through Socrates Plato states: “Love, in reality is of every good, not of the missing half of oneself; desire that it should be ever present with it. It acts as the desire of generation in the beautiful, in relation both to body and soul, a something immortal in mortality as it were; not of the beautiful; but of immortality, necessarily, without which nothing can be ever present.” Plato found that our desire to love implies universal goodness, and that there is a piece of the eternal inside every human being. Evil, Plato said, was an “illusion”. Love symbolizes immutable goodness everyone craves. Thus there is a hierarchy to love, the lowest being physical attraction, the middle wrung occupied by the pursuit of completeness within another person and finally the uppermost level being the love of ultimate reality.

Plato took the influences of his life and produced arguably the most influential body of philosophical works in the Western world. Concerning himself with human welfare and universal truths like justice and love, he recorded and improved upon the teachings of his martyred teacher, Socrates, and laid the groundwork for those who would succeed him, namely Aristotle. The Republic alone has challenged and delighted many hungry minds. Everyone lives in the broad shadow cast by the ideas of this great philosopher because anyone who wishes to appreciate modern society must first labor under his tutelage.

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Glitter And Doom: Tom Waits In Concert

"Lucinda / Ain't Going Down to the Well"

"Down in the Hole"

"Falling Down"

"Chocolate Jesus"

"All the World Is Green"

"Cemetery Polka"

"Cause of It All"

"Till the Money Runs Out"

"Such a Scream"

"November"

"Hold On"

"Black Market Baby"

"9th and Hennepin"

"Lie to Me"

"Lucky Day"

"On the Nickel"

"Lost in the Harbor"

"Innocent When You Dream"

"Hoist That Rag"

"Make It Rain"

"Dirt in the Ground"

"Get Behind the Mule"

"Hang Down Your Head"

"Jesus Gonna Be Here"

"Singapore"

ENCORE

"Eyeball Kid"

"Anywhere I Lay My Head"

Sunday, July 27, 2008

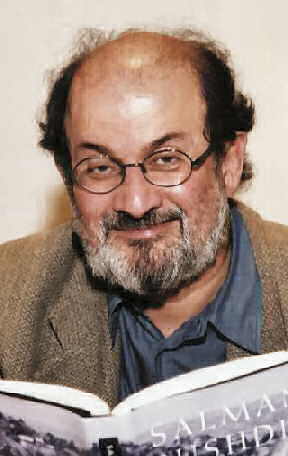

Salman Rushdie on "Here on Earth"

In Salman Rushdie’s latest wild and whirling novel, The Enchantress of Florence, a refugee from Florence ends up in the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar: A Muslim vegetarian, a warrior who wants only peace, a philosopher king and the first great Indian secularist. Jean Feraca talks with Salman Rushdie this hour on Here on Earth: Radio Without Borders.

Salman Rushdie on "Here on Earth"

It takes just one to change the world

"…If one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams,

and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined,

he will meet with success unexpected in common hours."

-- Henry David Thoreau

Judging from the title of his book it would be easy to confuse Eric Chaet as just another admirer of On The Road. This is not so. Kerouac's drug-infused travelogue taught a generation how to be hip, but Eric Chaet is not hip. Unlike Kerouac's loping, stream-of-consciousness free-for-alls Chaet's prose is precise and message-driven.

If comparisons need be made then Mr. Chaet's closest American literary counterpart would be Henry David Thoreau. Both authors are nature-focused individualists who wish to improve their interior as well as exterior worlds. Neither can be contained by a single label nor desire to be.

Chaet's mission statement is simple: change the world. He's even written a type of "manual" on how to do exactly that entitled How to Change the World Forever for Better. The author himself has tried several methods of achieving this goal from teaching Navajo students math, to hitchhiking across America's sunbelt, to Civic Action. Chaet has answered Thoreau's call for direct action when he declared for all citizens to "vote with our arms, with our legs, with our feet, with our whole bodies."

As a poet, essayist, short storyist, and raconteur Chaet has many tools in his tool chest. His literary voice is one of inimitable populism. His poems read like meditations from a world-weathered bookworm, and his short stories are typically first person vignettes of modest workers, flawed but brimming with potential.

To find out more about this artist listen to his July 27, 2008 interview, and for a sample of his writing visit his website "Eat Some, Plant Some". If you enjoy his work drop him a line and let him know you want to change the world forever for better too.

Eric Chaet interview on The Jane Crown Show

Eat Some, Plant Some

People I met Hitchhiking on USA Highways

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Friday, July 25, 2008

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

The good humor man

The good humor man

Who invented jokes, and why do we laugh at them? Jim Holt discusses the history of funny.

By James Hannaham

July 21, 2008 | A few years ago, wiry, loquacious New Yorker writer Jim Holt scrapped an ambitious philosophy book about "the puzzle of existence" when more practical matters caught up with him -- he was broke, having spent his big advance. Paradoxically, he decided to get out of that jam the same way he'd gotten into it -- by proposing another book. This time he chose not to pursue the cosmic joke of existence, but the history and philosophy of jokes. But the joke was on him. He thought it would be a "quick and appealing" book to write, and that he'd find a solid base of similar books about the history of jokes to use as source material, but there was, well, nothing. "Being terribly lazy, this was extremely irksome to me," Holt grumbles.

Somehow he overcame his indolence and wrote "Stop Me If You've Heard This," an entertaining and informative, if too-brief, overview of what we know about the setup/punch line anecdote throughout history, including a biography of its supposed inventor, the legendary Greek Palamedes, who is also credited with inventing "numbers, the alphabet, lighthouses, dice, and the practice of eating meals at regular intervals." Holt also introduces us to the 14th century Italian Poggio Bracciolini, who served as secretary to several popes during the Western Schism and wrote Europe's first joke book, the "Liber Facetiarum." Full of lascivious comments about virgins and bald female flashers, the "facetiae" also managed to escape papal censorship, proving how good it is to have friends in high places.

The second half of the book tackles deeper questions about humor: How does it work, and why? Though he could easily wax dry and analytical, Holt peppers his discourse with ribald and/or offensive riddles -- "Why should we feel sorry for the atheist? Because he has no one to talk to while getting a blow job" -- that prove his points and leaven his methodical approach to frivolity.

Salon sat down with Holt in New York for a rapid-fire low-residency seminar in hilarity, history and chimpanzee comedy.

Which theory of the evolution of humor do you find most convincing?

Well, there are these three theories of humor. The Superiority Theory -- that you laugh when you realize that you're better than someone else, so nasty jokes, racist jokes, jokes about gays and cuckolds and drunkards and henpecked husbands conform to that theory. Then there's Freud's Release Theory, which says that jokes are about ventilating forbidden impulses. The setup gets the forbidden material past the censor, and the punch line liberates your forbidden impulses for a moment. All of the psychic energy you used to repress them gets released and you laugh, expressed in chest-heaving, spasmodic laughter.

But then there's the one that makes the most sense to me, the Incongruity Theory, that jokes are about the pure intellectual pleasure we take in yanking together things that seem utterly dissimilar and perceiving similarities. In the 17th century, "wit" simply meant intelligence. As the meaning evolved, it came to mean the ability to see resemblances between apparently dissimilar things. Today it means the ability to see, to perceive or to take pleasure in absurdities or incongruities. That's the highest form of humor. As jokes get funnier, they rely more on incongruity and less on hostility and superiority or on sex and naughtiness.

So you think of humor as having evolved? In that case, what would a prehistoric joke be like?

A lot of what we say about prehistory is speculative. I gave a talk at the New York Institute for the Humanities a couple of months ago on the future of humor -- what jokes would be like in the year 1,000,000 -- and I used something called the Copernican principle, which is a way of predicting the distant future based on the distant past. Listen, if you want to know what's going to last for a long time, look at things that have already been around for a while. The Seven Wonders of the World -- when the list was drawn up in the third or fourth century, the oldest one was the Pyramid of Cheops. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, etc. -- and so what's the only one that has survived? The Pyramid of Cheops. All the other ones that were much newer when the list was drawn up disappeared. So I figured out what jokes looked like a million years ago by looking at what chimps find funny, because whatever's oldest is most likely to last, based on the Copernican principle.

So what's a good chimp joke?

Chimps laugh, and the lineage between us and them spread about 5 million years ago, so we can assume that unless laughter evolved separately, it did so before the two lineages split. Chimps who have been taught sign language not only laugh, but they can be taught to sign "funny." And they like incongruity. Washoe, the chimp who was taught sign language by Roger Fouts, thought it was really funny to present one of the researchers with a rock and call it food. Another chimp, Mojo, thought it was really funny, say, that a purse was a shoe and put it on her foot. So this is delight in sheer absurdity. It's only with civilization that you get sexual repression, hence the possibility of sex jokes, or in-groups and out-groups for ethnic jokes, and so on. Civilization is relatively recent -- it's only existed for about 6,000 years. And I define civilization as cities plus writing plus sexual repression. So in our humor, sexual repression will go away, in-groups and out-groups will go away, and in the end we'll be left with sheer absurdity, and it'll be purely intellectual.

Monty Python fans, rejoice!

But then you have to ask yourself -- why should a purely intellectual stimulus cause laughter, this gross physical response?

How about I ask you. Why?

The best theory I know of is the False Alarm Theory. You're out with some of the members of your extended group in the African savannah, and there's suddenly an apparent threat. There's something that looks like a snake in front of you. Suddenly tensions rise, and you and the other members of the band go into fight-or-flight mode. Then someone realizes, "Oh it's not a snake, it's just a big piece of thing hanging down from a tree." And so he emits this stereotyped signal that tells everyone else what seemed to be a threat is actually nothing. Laughter is the stereotyped reflex or signal, and it's also contagious, so the information quickly spreads through the band. So what happens is that a strained expectation suddenly dissolves into nothing.

That's bizarre. How is a joke like being afraid you'll get attacked in a rain forest?

It isn't exactly the same, obviously. But the process of tension and release has a similar rhythm. Even a really stupid joke has that same pattern: Why is it so hard to find the composer of the "Surprise Symphony"? Because he's Haydn! When I first heard that, I really wracked my brain -- what could this mean? You start to think about it and you're tense because you're not quite getting it, then suddenly the ambiguity is revealed by the punch line, and it turns out to be trivial. You release all your pent-up energy. That's the best theory I know of.

I have a special fondness for those jokes that are jokes only in terms of form, where the setup makes you expect something clever, and instead the punch line is shockingly mundane, or crude. For instance, Why did the monkey fall out of the tree?

I don't know.

Because it was dead. Why can't Marilyn Monroe eat M&M's?

Why?

Because she's dead.

That conforms to the classic joke paradigm, though. You think there's a semi-serious query in the setup, and it dissolves into nothing, and there's that sort of tension -- even after you told me the one about the monkey being dead, I still tried to solve the Marilyn Monroe one, and laughed partly to cover up my own obtuseness.

That's another terrible thing about jokes, they function as a test for social inclusion. If you're among friends and someone tells a joke and you're the one who doesn't get it, you're doubly excluded -- first of all, you miss out on the fun of it, then everyone looks at you. This happened when Dan Quayle was vice president, and a friend of mine was invited to a luncheon he had for the press. The idea was that Quayle's handlers would prove to the press that he was actually a fairly clever, interesting guy despite all appearance to the contrary. Quayle rarely seemed to laugh at the jokes they told, but every once in a while he would laugh after a slight delay, and then he would proceed to explain the joke to everyone.

The joke they'd already laughed at.

Right.

Do you think that joke telling suffers during times of repression?

Well, there are periods when the art of joke telling disappears for centuries at a time. But in some cases, jokes have flourished under authoritarian regimes. In the former Soviet Union, there was a very lively joke-telling culture. Actually a guy has just published a book of Soviet jokes, with the unfortunate title "Hammer and Tickle." The book tells the story of the dissolution of the Soviet Union by retelling jokes from different eras. They have a really satisfying bitter humor: A guy needs a car, so he goes to a dealer in Moscow who shows him two models. He chooses the one color they have and he pays for the car. The dealer says, "Your car will be ready in exactly 10 years." And the guy says, "Oh, in the morning or the afternoon?" And the dealer says, "What does it matter?" and he says, "The plumber's coming in the morning." It doesn't exactly get to the heart of what was wrong with the Soviet economy, but it's socially therapeutic.

Laughter is a permanent critique of all values, a way of exposing cant and hypocrisy and social injustice in the swiftest possible way before even actually formulating an argument. In a way, you don't even need to formulate an argument, because if the humor is sufficiently good, the system eventually collapses.

Racism

Racism

- a talk given by Trish on October 19, 1994

(View Original)Any discussion of Racism needs to examine the roots of Racism in order to understand it and to struggle against it effectively. There are basically 3 explanations for the existence of racism.

The dominant view which is rarely expressed as a worked out theory but rather operates at the level of assumptions is that racism is an irrational response to difference which cause some people with white skin to have hateful attitudes to people with black skin which sometimes leads to violent and evil actions. People who have this understanding of racism advocate awareness and education as a way of preventing the practice of racism.

The second view is that racism is endemic in white society and that the only solution is for black people to organise "Themselves separately from whites " in order to defend themselves and to protect their interests.

The third view and the one which I am advocating is an explanation of racism based on a materialist perspective, which views racism as a historically specific and materially caused phenomenon. Racism is a product of capitalism. It grew out of early capitalisms' use of slaves for the plantations of the new world, it was consolidated in order to justify western and white domination of the rest of the world and it flourishes today as a means of dividing the working class between insiders and outsiders, native and immigrants and settled and Travellor in the Irish context.

It is necessary to examine the underlying assumptions about racism in more detail in order to arrive at the materialist analysis of it. Racism is commonly assumed to be as old as society itself. However this does not stand up to historical examination. Racism is a particular form of oppression: discrimination against people on the grounds that some inherited characteristic, for example, colour, makes them inferior to their oppressors.

However, historical references indicate that class society before capitalism was able, on the whole, to do without this particular form of oppression. Bad as the society of classical Greece and Rome were it is historically pretty well proven that the ancient Greeks and Romans knew nothing about race. Slaves were both black and white and in fact the majority of slaves were white. The first clear evidence of racism occurred at the end of the 16th century with the start of the slave trade from Africa to Britain and to America.

CLR James Modern Politics writes that 'the conception of dividing people by race begins with its slave trade. Thus this (the slave trade) was so shocking, so opposed to all the conceptions of society which religious and philosophers had . . .the only justifications by which humanity could face it was to divide people into races and decide that Africans were an inferior race"

So racism was formed as an attempt to justify the most appalling and inhuman treatment of black people in the time of the greatest accumulation of material wealth the world had seen until then.

By the end of the 17th century, racism had become an established, systematic and conscious justification for the most degrading forms of slavery.

The justification of slavery by an ideology of racism started to fade under attack by abolotionists and with the decline of the slave trade. Racism, however took on a new form as a justification for the ideology of imperialism. This racism of empire was dominant for over a century from the 1840's on. Concepts such as the "white man's burden" became fashionable especially in England where British Colonialists liked to cast themselves as father and mother with a clear duty to take responsibility for the material and spiritual well-being of their 'colonial' children. Racism became the ideological justification of capitalism's expansion into conquering countries, plundering their wealth and exploiting the natives.

When white imperialism was at its height, a new expression of racism was taking shape - that is anti-immigrant racism which was typified in England by racist opposition to new immigrants from Ireland. The expansion of capitalism required the importation of foreign workers, a trend which continued in industrialised European countries and in America and Australia up to the 1980's. The long boom of British capitalism after the 2nd world war, for example, encouraged the immigration of West Indians and Asians to Britain. These so called foreign workers provided the employers with the basis for encouraging a split within the workforce.

The same happened in Germany with the immigration of Turkish workers, and the same kind of anti-immigrant agitation emerged in many other European countries and is the main focus of racism in these countries today. Racial attacks on non-white immigrants and on Gypsies have become almost commonplace in parts of Germany and in England. This form of racism has been fueled by economic crisis and by capitalism's need to find a convenient scapegoat for unemployment, housing shortages and every other problem which the current crisis of capitalism has thrown up. Immigration controls, and racist anti-immigration laws have grown up in response to this expression of racism.

On this point, people should be aware that Ireland has the worst immigrant laws in Europe and that they are specifically racist and have been used to exclude non-whites and Jews from this country on many occasions.

Racism and anti semitism

Anti semitism is generally considered to be a variety of racism. It has taken different forms over the centuries, being justified on religious grounds during the middle ages, for example. Ruth Benedict argues "during the middle ages persecutions of the Jews, like all medieval persecutions were religious rather than racial. As racist persecutions replaced religious persecutions in Europe, however, the inferiority of the Jew became that of race".

As recent anti semitism took hold in Europe in the 1890's, Jews started to be attacked not for what they did but for what their forefathers were. This is what racial anti-semitism means. This kind of anti-semitism found an echo in some parts of the working class where Jews were identified as capitalist parasites and userors even though the reality in Britain, anyway, was that most Jews were in fact workers. Racial anti-semitism was a useful way to deflect attacks for the real problems created by capitalism in general.

Facism

Anti semitism and racism are not an essential component of fascism which is essentially a mass movement of the middle class and petit bourgeois built in periods of defeat for the working class when even the most basic trade union organisation is a threat to profits of capital.

In Italy, for example, Jews were encouraged to join the fascist party in its early days.

In Germany, however, the economic condition were ripe for the growth of anti semitism. Leon argues that "the economic catastrophe of 1929 threw the petty bourgeois masses into a hopless situation . . . the petty bourgeois regarded their Jewish competitors with growing hostility." Jewish capital was attacked by the Nazis which appealed to the anti-capitalist instinct of German workers and support for Hitler's Nazi Party rocketed. Anti Semitism was also an important part of a Nazi racial philosophy which justified 'Aryan' supremacy and the need to develop 'Aryan' racial purity.

The Nazi holocaust in which 6 million Jews were murdered alongside an equal number condemned either as political opponents of Hitler or as members of other 'inferior' groups such as Slavs, gays, Gypsies and the mentally ill represented racism and capitalism in their most extreme and barbarous form.

Race and Culture The concept of race or racial difference is essentially an artificial one as all of humanity is actually the one race. In recent times, the concept of culture has been used to discriminate against groups of people when racial discrimination was officially outlawed.

Culture is essentially the way that different group of people acquire a particular world view, a way of making sense of the world from particular social, economic, environmental and demographic conditions. Cultures are not static, they change all the time in response to a wide variety of factors.

Racists sometimes argue "I have nothing against Asians or Blacks as people, it's just that their culture is incompatible with the British/German/French way of life." This is a nonsense argument as all groups of people have a culture and their culture is an essential part of what they are as is their skin colour. Likewise, some anti-racist work especially in schools adopts a "colour blind" approach to the issue and introduce pupils to the more exotic and acceptable aspects of non-white culture while ignoring the materialist nature of racism. This is known as the "saris and samosas" style of anti-racist work and is obviously of very limited use.

Racism which is focussed on a hatred of another groups culture, as it is in the case of Travellors and Gypsies, is sometimes harder to identify clearly as racism because the victims are sometimes white. However, the power relationship which is one of domination and oppression is the key to identifying the reality of racism in these situations.

Response and strategies for fighting racism

The strategies adopted to fight racism depend on the analysis. They basically break down into reformist strategies and revolutionary ones.

The American experience illustrates some of the strategies that have been used. Militant civil rights campaigns such as those which took place in the 1960's in America with leaders such as Martin Luther King succeeded in gaining basic civil rights for black and in forcing the dismantling of the worst forms of institutional racism. It involved mass civil disobedience and voter registration campaigns.

However, the leaders of the movement were middle class with no concept of the need for working class unity. Although many very worthwhile reforms were won, racism remained very mush part of American society. Another more radical strategy associated with Malcolm X was that of black nationalism and black separatism. Racism is defined as endemic to white so like that of the unemployed in the fifties. The Irish National Organisiation of the Unemployed is entirely dominated by Union hacks, poverty pimps, CV tripers and time servers.

We should not be entirely pessemistic. We know that things can change quick, fast and in a hurry. The massive mobilisiation in the case of the autorney general Versus the X case and the climbdown it caused is ample proof of this. We can't afford to throw up our hands and give up on activism. We must not retreat into the realmhe roots of racism in this strategy.

As revolutionaries, we recognise the material basis of racism and its use under capitalism to divide workers, set foreign workers against natives and to provide convenient scapegoats for all the problems capitalism produces. It can only be defeated by a class based strategy which aims to unite non-white and white workers in a struggle for anarchism.

Finally, it is important for us to be aware of the devastating effects of racism at a personal and at a community level. To be black, Asian, a Travellor or a member of an ethnic or cultural minority in most Western countries is a debilitating experience.

Racism shatters individuals self confidence and self image and leads to poor mental and physical health. It can destroy communities subjected to it as it almost has done in the case of Native Americans and Australian Aborigines, for example.

For this reason, it is important to challenge individual acts of racism when we come across them as well as campaigning politically against it.

Socialist Candidate Brian Moore on WPR

(View Original)

Brian Moore is the 2008 Socialist Party USA presidential candidate. What are his views on the issues? After four, Ben Merens and his guest discuss the Socialist Party USA platform and its 2008 campaign for the presidency.

Socialist Candidate Brian Moore on WPR

Moore/Alexander ’08

Monday, July 21, 2008

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Intelligent Design/Evolution Debate

Table of Contents: http://www.youtube.com/view_play_list...

December 19, 1997 -

ID Proponents: William F. Buckley Jr., Phillip Johnson, Michael Behe, and David Berlinski

Evolutionist: Barry Lynn, Eugenie C. Scott, Michael Ruse, and Kenneth Miller

Transcript: http://www.bringyou.to/apologetics/p4...

Audio: http://www.bringyou.to/FiringLine1997...

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Sunday, July 13, 2008

How-to Crash the RNC Convention

A Minnesota Anarchist group called the "RNC Welcoming Committee" plans on "crashing" the Republican National Convention in September, setting up blockades and demonstrations in an attempt to prevent the delegates from entering the event. Almost on cue the local media picked up the story and added their spin. Even FOX News reported on the event. And, of course, they used everybody's favorite Anarchist stereotypes such as the threat of violence and portentous secrecy. In fact, news outlets claim the plans were "leaked" which isn't accurate as they were always available to the public. The plans were placed on the web by the group itself and their agenda remains transparent to anybody who's interested.

Take a gander at the news coverage:

And take a listen to the RNC Welcoming Committee's intentions on their radio broadcast.

As for the event itself. They are encouraging radicals, moderates, liberals, pissed-off conservatives, and warm bodies of every sort to swarm the convention, seize SPACE and engage in direct action. They will be present at the convention all four days (September 1-4). For more information check out their website: http://www.nornc.org/

See you in September!We're getting ready

Saturday, July 12, 2008

Meeting Spain’s last anarchist

From the BBC News Americas Website

Meeting Spain's last anarchist

By Alfonso Daniels

San Buenaventura, Bolivia

Hours after flying on a rickety 19-seater propeller plane and landing on a dirt strip, you get to the village of San Buenaventura in the heart of the Bolivian Amazon.

Here, in a simple one-storey brick house next to a row of wooden shacks, is the home of Antonio Garcia Baron.

He is the only survivor still alive of the anarchist Durruti column which held Francoist forces at bay in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the founder of an anarchist community in the heart of the jungle.

Mr Baron, 87, was wearing a hat and heavy dark glasses. He later explained that they were to protect his eyes, which were damaged when he drank a cup of coffee containing poison nine years ago.

It was, he said, the last of more than 100 attempts on his life, which began in Paris, where he moved in 1945 after five years in the Mauthausen Nazi concentration camp, and continued in Bolivia, his home since the early 1950s.

Stateless

He was keen to share his views on 20th Century Spanish history with a wider audience.

"The Spanish press has covered up that the (Catholic) Church masterminded the death of two million Republicans during the civil war, not one million as they maintain," Mr Baron said before launching into one of his many anecdotes.

"I told Himmler (the head of the Nazi SS) when he visited the Mauthausen quarry on 27 April, 1941, what a great couple the (Nazis) made with the Church.

"He replied that it was true, but that after the war I would see all the cardinals with the Pope marching there, pointing at the chimney of the crematorium."

On the walls of Mr Baron's house is a picture of him taken in the camp. Next to it is a blue triangle with the number 3422 and letter S inside, marking the prisoners considered stateless.

"Spain took away my nationality when I entered Mauthausen, they wanted the Nazis to exterminate us in silence. The Spanish government has offered to return my nationality but why should I request something that was stolen from me and 150,000 others?" he said angrily.

Mr Baron arrived in Bolivia on the advice of his friend, the French anarchist writer Gaston Leval.

"I asked him for a sparsely populated place, without services like water and electricity, where people lived like 100 years ago - because where you have civilisation you'll find priests."

Some 400 people, mostly Guarani Indians, lived there at the time, but in fact also a German priest.

"He was a tough nut to crack. He learnt of my arrival and told everyone that I was a criminal. They fled and made the sign of the cross whenever they saw me, but two months later I started speaking and they realised I was a good person, so it backfired on him."

Convinced that the priest still spied on him, a few years later he decided to leave and create a mini-anarchist state in the middle of the jungle, 60km (37 miles) and three hours by boat from San Buenaventura along the Quiquibey River.

With him was his Bolivian wife Irma, now 71.

They raised chicken, ducks and pigs and grew corn and rice which they took twice a year to the village in exchange for other products, always rejecting money.

Dunkirk

Life was tough and a few years ago Mr Baron lost his right hand while hunting a jaguar.

For the first five years, until they began having children, they were alone. Later a group of some 30 nomadic Indians arrived and decided to stay, hunting and fishing for a living, also never using money.

"We enjoyed freedom in all of its senses, no-one asked us for anything or told us not to do this or that," he recounted as his wife smiled, sitting in a chair at the back of the room.

Recently they moved back to the village for health reasons and to be closer to their children. They live with a daughter, 47, while their other three children, Violeta, 52, Iris, 31, and 27-year-old Marco Antonio work in Spain.

They also share the few simple rooms arranged around an internal patio with three Cuban doctors who are part of a contingent sent to help provide medical care in Bolivia.

The hours passed and it was time to take the small plane back to La Paz before the torrential rain isolated the area again.

Only then, as time was running out, did Mr Baron begin speaking in detail about Mauthausen and the war - as if wishing to fulfil a promise to fallen comrades.

How the Nazis threw prisoners from a cliff, how some of them clung to the mesh wire to avoid their inevitable death, how the Jews were targeted for harsh treatment and did not survive long.

His memory also took him to Dunkirk where he had arrived in 1940, before he was caught and imprisoned in Mauthausen.

"I arrived in the morning but the British fleet was some 6km from the coast. I asked a young English soldier if it would return.

"I saw that he was eating with a spoon in one hand and firing an anti-aircraft gun with the other," he laughed.

"'Eat if you wish', I told him. 'Do you know how to use it?' he asked since I didn't have military uniform and was very young.

"'Don't worry,' I said. I grabbed the gun and shot down two planes. He was dumbstruck.

"I'll never forget the determination of the British fighting stranded on the beach."

Friday, July 11, 2008

Monday, July 07, 2008

Surviving the Fourth of July

Surviving the Fourth of July

I survive the degradation that has become America — a land that exalts itself as a bastion of freedom and liberty while it tortures human beings, stripped of their rights, in offshore penal colonies, a land that wages wars defined under international law as criminal wars of aggression, a land that turns its back on its poor, its weak, its mentally ill, in a relentless drive to embrace totalitarian capitalism — because I read books. I have 5,000 of them. They line every wall of my house. And I do not own a television.

I survive the gradual, and I now fear inevitable, disintegration of our democracy because great literature and poetry, great philosophy and theology, the great works of history, remind me that there were other ages of collapse and despotism. They remind me that through it all men and women of conscience endured and communicated, at least with each other, and that it is possible to refuse to participate in the process of self-annihilation, even if this means we are pushed to the margins of society. They remind me, as the poet W.H. Auden wrote, that “ironic points of light flash out wherever the Just exchange their messages.” And if you tire, as all who can think critically must, of the empty cant and hypocrisy of John McCain and Barack Obama, of the simplistic and intellectually deadening epistemology of television and the consumer age, you can retreat to your library. Books were my salvation during the wars and conflicts I covered for two decades as a foreign correspondent in Central America, Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans. They are my salvation now. The fundamental questions about the meaning, or meaninglessness, of our existence are laid bare when we sink to the lowest depths. And it is those depths that Homer, Euripides, William Shakespeare, Fyodor Dostoevsky, George Eliot, Joseph Conrad, Marcel Proust, Vasily Grossman, George Orwell, Albert Camus and Flannery O’Connor understood.

“The practice of art isn’t to make a living,” Kurt Vonnegut said. “It’s to make your soul grow.”

The historian Will Durant calculated that there have been only 29 years in all of human history during which a war was not under way somewhere. Rather than being aberrations, war and tyranny expose a side of human nature that is masked by the often unacknowledged constraints that glue society together. Our cultivated conventions and little lies of civility lull us into a refined and idealistic view of ourselves. But look at our last two decades-2 million dead in the war in Afghanistan, 1.5 million dead in the fighting in Sudan, some 800,000 butchered in the 90-day slaughter of Tutsis and moderate Hutus by soldiers and militias directed by the Hutu government in Rwanda, a half-million dead in Angola, a quarter of a million dead in Bosnia, 200,000 dead in Guatemala, 150,000 dead in Liberia, a quarter of a million dead in Burundi, 75,000 dead in Algeria, at least 600,000 dead in Iraq and untold tens of thousands lost in the border conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, the fighting in Colombia, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Chechnya, Sri Lanka, southeastern Turkey, Sierra Leone, Northern Ireland, Kosovo. Civil war, brutality, ideological intolerance, conspiracy and murderous repression are the daily fare for all but the privileged few in the industrialized world.

“The gallows,” the gravediggers in “Hamlet” aptly remind us, “is built stronger than the church.”

I have little connection, however, with academics. Most professors of literature, who read the same books I read, who study the same authors, are to literature what forensic medicine is to the human body. These academics seem to spend more time sucking the life out of books than absorbing the profound truths the authors struggle to communicate. Perhaps it is because academics, sheltered in their gardens of privilege, often have hyper-developed intellects and the emotional maturity of 12-year-olds. Perhaps it is because they fear the awful revelations in front of them, truths that, deeply understood, would demand they fight back. It is easier to eviscerate the form, the style and the structure with textual analysis and ignore the passionate call for our common humanity.

“As long as reading is for us the instigator whose magic keys have opened the door to those dwelling-places deep within us that we would not have known how to enter, its role in our lives is salutary,” Proust wrote. “It becomes dangerous, on the other hand, when, instead of awakening us to the personal life of the mind, reading tends to take its place. …”

Although Shakespeare’s Jack Falstaff is a coward, a liar and a cheat, although he embodies all the scourges of human frailty Henry V rejects, I delight more in Falstaff’s address to himself in the Boar’s Head Tavern, where he at least admits to serving to his own hedonism, than I do in Henry’s heroic call to arms before Agincourt. Falstaff personifies a lust for life and the mockery of heaven and hell, of the crown and all other instruments of authority. He disdains history, honor and glory. Falstaff is a much more accurate picture of the common soldier who wants to save his own hide and finds little in the rhetoric of officers who urge him into danger. Prince Hal is a hero and defeats Percy while Falstaff pretends to be a corpse. But Falstaff embodies the basic desires we all have. He is baser than most. He lacks the essential comradeship necessary among soldiers, but he clings to life in a way a soldier under fire can sympathize with. It is to the ale houses and the taverns, not the court, that these soldiers return when the war is done. Jack Falstaff’s selfish lust for pleasure hurts few, while Henry’s selfish lust for power leaves corpses strewn across muddy battlefields. And while we have been saturated with the rhetoric of Henry V this past July 4 holiday we would be better off listening to the truth spoken by Falstaff.

There is a moment in “Henry IV, Part I,” when Falstaff leads his motley band of followers to the place where the army has assembled. Lined up behind him are cripples and beggars, all in rags, because those with influence and money, like George W. Bush, evade military service. Prince Hal looks askance at the pathetic collection before him, but Falstaff says, “Tut, tut, good enough to toss, food for powder, food for powder. They’ll fill a pit as well as better. Tush, man, mortal men, mortal men.”

I have seen the pits in the torpid heat in El Salvador, the arid valleys in northern Iraq and the forested slopes in Bosnia. Falstaff is right. Despite the promises never to forget the sacrifices of the dead, of those crippled and maimed by war, the loss and suffering eventually become superfluous. The pain is relegated to the pages of dusty books, the corridors of poorly funded VA hospitals, and sustained by grieving families who still visit the headstone of a man or woman who died too young. This will be the fate of our dead and wounded from Iraq and Afghanistan. It is the fate of all those who go to war. We honor them only in the abstract. The causes that drove the nation to war, and for which they gave their lives, are soon forgotten, replaced by new ones that are equally absurd.

Stratis Myrivilis in his novel “Life in the Tomb” makes this point:

“A few years from now, I told him,” Myrvilis wrote nearly a century ago, “perhaps others would be killing each other for anti-nationalist ideals. Then they would laugh at our own killings just as we had laughed at those of the Byzantines. These others would indulge in mutual slaughter with the same enthusiasm, though their ideals were new. Warfare under the entirely fresh banners would be just as disgraceful as always. They might even rip out each other’s guts then with religious zeal, claiming that they were ‘fighting to end all fighting.’ But they too would be followed by still others who would laugh at them with the same gusto.”

Patriotic duty and the disease of nationalism lure us to deny our common humanity. Yet to pursue, in the broadest sense, what is human, what is moral, in the midst of conflict or under the heel of the totalitarian state is often a form of self-destruction. And while Shakespeare, Proust and Conrad meditate on success, they honor the nobility of failure, knowing that there is more to how a life is lived than what it achieves. Lear and Richard II gain knowledge only as they are pushed down the ladder, as they are stripped of power and the illusions which power makes possible.

Late one night, unable to sleep during the war in El Salvador, I picked up “Macbeth.” It was not a calculated decision. I had come that day from a village where about a dozen people had been murdered by the death squads, their thumbs tied behind their backs with wire and their throats slit.

I had read the play before as a student. Now it took on a new, electric force. A thirst for power at the cost of human life was no longer an abstraction. It had become part of my own experience.

I came upon Lady Macduff’s speech, made when the murderers, sent by Macbeth, arrive to kill her and her small children. “Whither should I fly?” she asks.

I have done no harm. But I remember now

I am in this earthly world, where to do harm

Is often laudable, to do good sometime

Accounted dangerous folly.Those words seized me like Furies and cried out for the dead I had seen lined up that day in a dusty market square, and the dead I would see later: the 3,000 children killed in Sarajevo, the dead in unmarked mass graves in Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, Sudan, Algeria, El Salvador, the dead who are my own, who carried notebooks, cameras and a vanquished idealism into war and never returned. Of course resistance is usually folly, of course power exercised with ruthlessness will win, of course force easily snuffs out gentleness, compassion and decency. In the end, all we can cling to is each other.

Thucydides, knowing that Athens was doomed in the war with Sparta, consoled himself with the belief that his city’s artistic and intellectual achievements would in the coming centuries overshadow raw Spartan militarism. Beauty and knowledge could, ultimately, triumph over power. But we may not live to see such a triumph. And on this weekend of collective exaltation I did not attend fireworks or hang a flag outside my house. I did not participate in rituals designed to hide from ourselves who we have become. I read the “Eclogues” by Virgil. These poems were written during Rome’s brutal civil war. They consoled me in their wisdom and despair. Virgil understood that the words of a poet were no match for war. He understood that the chant of the crowd urges nearly all to collective madness, and yet he wrote with the hope that there were some among his readers who might continue, even when faced with defeat, to sing his hymns of compassion.

… sed carmina tantum

nostra valent, Lycida, tela inter Martia, quantum

Chaonias dicunt aquila veniente columbas.…but songs of ours

Avail among the War-God’s weapons, Lycidas,

As much as Chaonian doves, they say, when the

eagle comes.* * *

Chris Hedges, who graduated from Harvard Divinity School and was for nearly two decades a foreign correspondent for The New York Times, is the author of “American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America.“

Copyright © 2008 Truthdig, L.L.C.