by Dan O'Connor

(http://mises.org/story/3766)

[An MP3 audio file of this article, read by Floy Lilley, is available for download.]

"How selfish so ever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it."

"How selfish so ever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it."One of the few places in the world not yet plagued by government intervention is the internet. Although some governments in certain parts of the world have infiltrated the activities of the internet to varying degrees, it remains the closest thing to a purely free economy that we can identify in the modern world.

On the internet, the beautiful aspects of human nature manifest themselves, and we see individuals and companies maximizing their talents and resources for reasons of profit, pleasure, altruism, and mere progress in itself. Given that the government neither inhibits the activities of the internet nor props up or favors any particular actors or individuals, perhaps we are witnessing the closest thing to a free market that man has ever witnessed.

Although many consider the America of the 19th century to be the closest thing to a purely free market, in fact, congressmen constantly acted in favor of certain individuals, leading in some cases to monopolistic advantages. Ironically, at the end of the century the government intervened in an attempt to break up monopolies.

So here we are in a worldwide web that connects people from all parts of the world, allowing them to exchange whatever they want with one another. It is the essence of a free market: voluntary exchange. There is no use of force or coercion on the internet. No higher authority effectively controls or dictates the way that we spend our time online or the activities that we partake in. Although some legal obstacles inhibit people from accessing certain sites and materials, given the lack of regulation or enforcement by a higher authority, users are easily able to circumvent these restrictions and achieve the things that they want.

As it evolves, we begin to witness the endless potential that exists within the internet and the unquantifiable benefits it provides to society. Although the internet currently represents freedom from both a civil and a social perspective, I shall examine it from an economic perspective.

Arguably, the human race has seen more progress and innovation through the use of the internet in the past 20 years than through the use of any innovation known in the history of mankind. As we reflect back over the last 20 years, we see thousands of amazing success stories. We see entrepreneurs from all different economic backgrounds and classes making full use of their skills, ideas, and passions. We read about success stories such as Facebook and Google, where very young people have been able to generate massive wealth while providing a cheap, convenient, and valuable new tool for everyone across the globe to enjoy. This is the beauty of a system free from government intervention.

In fact, it's such a free market that government doesn't even effectively enforce intellectual property and copyright protection. And what is the result? We see entrepreneurs from other countries imitating successful online programs with very little detriment to the originators. In fact, Chinese entrepreneurs have created very similar programs to both Google and Facebook. As a result, all of these companies have been able to generate profits while their users still enjoy the programs at no cost.

"Very young people have been able to generate massive wealth while providing a cheap, convenient, and valuable new tool for everyone across the globe to enjoy."In turn, their Chinese competitors bring increased competition to both Google and Facebook, creating incentives for them to improve their own products and continue to innovate. This example closely resembles capitalist Americans emulating European technology in the 19th century or Japanese entrepreneurs emulating Western technology during the process of their development.

Do patent protection laws truly promote greater and faster innovation? Some companies and individuals are able to avert these government-imposed rigidities online. And the success of this less-inhibited marketplace demonstrates the lack of need for patent protection laws.

If patent-protection laws, taxes, and legal-tender laws were completely eliminated from the internet, we would then see a purely free market. Although this is not foreseeable given the world's current political system, we can still continue to enjoy the advantages of this relatively unfettered aspect of modern society.

Technological advancements benefit society for many obvious reasons. In an unfettered marketplace, innovation reduces costs for businesses and hence prices for consumers. For example, in the past, some families spent several hundred dollars every few years just to update their encyclopedia set, even though all of the content in these encyclopedias was publicly accessible; the encyclopedia companies merely compiled the information into a more concise format.

Although these companies provided a very valuable product to society, there is now a decreased need for physical encyclopedias due to the increase of information available on the internet. Let us hope the Obama administration does not attempt to "bailout" Britannica anytime soon.

We begin to see so many things being offered on the internet not only for very cheap prices, but for free. Information that used to cost individuals and companies exorbitant fees can now be found on the internet freely, thus allowing individuals and companies to spend that money elsewhere, improving their own operations.

Before the internet took off in the 1990s, businesses across the United States spent billions of dollars every year on information. Nowadays, companies save millions of dollars per year on research, data, and inventory, which can now be spent on other areas of the business, such as rewarding employees with higher bonuses or purchasing new facilities and advanced equipment. The economy as a whole is operating more efficiently, as overall costs and expenditures have gone down.

"Let us hope the Obama administration does not attempt to "bailout" Britannica anytime soon."Often the most neglected benefit of technology for society is decreased prices. During and after the time of the Industrial Revolution in the United States, we witnessed a myriad of price reductions across most industries. As prices dropped and the cost of living decreased, individuals and entrepreneurs were encouraged to identify other niches throughout the market and introduce new technologies.

Unfortunately, much of modern society has a hard time grasping the benefit of price decreases, while central banks throughout the world continue to print money, which leads to price increases.

In modern times, we can purchase almost any sort of product via the internet and can access almost any information that we desire. When we consider the vast number of people and companies throughout society that earn profits by merely providing information, we can only imagine the enormous costs that can be saved as a result of more accessible and cheaper (often free) information now available to all of society online. What is even more encouraging is that we see the providers of this information doing so for reasons other than profit — a reflection of man's pursuit of passion and his innate sense of compassion.

Unfortunately, as has always been the case, the internet and its infinite value to society is threatened by a ubiquitous force: government. As we've seen throughout history, when companies become threatened by competitors, they do whatever is possible to prevent or squash competition — often through the use of government force.

In the 1930s, unions used various means for lobbying in DC in an attempt to introduce a minimum wage law, which ultimately passed. Smaller companies who could not afford to pay these increased wages were soon forced out of business.

Sure enough, various actors in DC are now lobbying to regulate the internet. In April 2009, AP began to publicize a widespread attack on Google — arguably the most successful company and widely enjoyed technology of the past 10 years. As more and more information-providing companies see their revenues dwindle as a result of better and more convenient information being provided by competitors on the internet, we can be certain that a greater number of companies will congregate in DC to propose greater regulation.

Let us hope our government is stern enough to defend the Constitution as it was written with the intent of dealing with this type of dilemma. The first amendment, freedom of the press, was most strongly emphasized by Thomas Jefferson. He stated, "Where the press is free and every man able to read, all is safe."

The internet is a model of the free market. It represents all of the aspects of capitalism that we cannot witness in our current offline world due to the high level of government intervention that pervades our society. Online, we see widespread competition, low barriers to entry, voluntary exchange, rapid technological advancements, decreased prices, and a flowering of creativity.

Dan O'Connor has lived in Asia since early 2004. Send him mail. See Dan O'Connor's article archives.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Witness the Freest Economy: the Internet

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Friday, October 09, 2009

The Conscience of a Capitalist

By STEPHEN MOORE

(http://online.wsj.com/articl/SB10001424052748704471504574447114058870676.html)The Whole Foods founder talks about his Journal health-care op-ed that spawned a boycott, how he deals with unions, and why he thinks CEOs are overpaid.

I honestly don't know why the article became such a lightning rod," says John Mackey, CEO and founder of Whole Foods Market Inc., as he tries to explain the firestorm caused by his August op-ed on these pages opposing government-run health care. "I think a lot of people who got angry haven't read what I actually wrote. There was a lot of emotional reaction—fear and anger. I just wanted to get people to think about whether there was a better way to reform the system."Mr. Mackey has flown into Washington, D.C., for a board meeting of the Global Animal Partnership, a group that advocates for the humane treatment of animals. There was no private jet: He arrived on Southwest Airlines from Austin, Texas, and he bought the "Wanna Getaway" bottom basement fare. "I barely got the last aisle seat," he says. While in town he stays in the bedroom of his regional president, who lives in Maryland.

For the 12th straight year, Mr. Mackey's company has been praised as one of the "100 Best Companies to Work For" by Fortune Magazine. Whole Foods sells healthy food, practices "socially responsible trade," and prides itself on promoting foods that are grown to support "biodiversity and healthy soils." Mr. Mackey donates 5% of company profits to charity and has been one of America's loudest critics of runaway compensation on Wall Street. And he pays himself $1 a year. He would seem to be a model corporate citizen.

Yet his now famous op-ed incited a boycott of Whole Foods by some of his left-wing customers. His piece advised that "the last thing our country needs is a massive new health-care entitlement that will create hundreds of billions of dollars of new unfunded deficits and move us closer to a complete government takeover of our health-care system." Free-market groups retaliated with a "buy-cott," encouraging people to purchase more groceries at Whole Foods.

Why did he write the piece in the first place?

"President Obama called for constructive suggestions for health-care reform," he explains. "I took him at his word." Mr. Mackey continues: "It just seems to me there are some fundamental reforms that we've adopted at Whole Foods that would make health care much more affordable for the uninsured."

What Mr. Mackey is proposing is more or less what he has already implemented at his company—a plan that would allow more health savings accounts (HSAs), more low-premium, high-deductible plans, more incentives for wellness, and medical malpractice reform. None of these initiatives are in any of the Democratic bills winding their way through Congress. In fact, the Democrats want to kill HSAs and high-deductible plans and mandate coverage options that would inflate health insurance costs.

The Whole Foods health-care story has been largely ignored by proponents of a government-run system. But it could be a template for those in Washington who want to drive down costs and insure the uninsured.

Mr. Mackey says that combining "our high deductible plan (patients pay for the first $2,500 of medical expenses) with personal wellness accounts or health savings accounts works extremely well for us." He estimates the plan's premiums plus other costs at $2,100 per employee, and about $7,000 for a family. This is about half what other companies typically pay. "And," he is quick to add, "we do cover pre-existing conditions after one year of service."

Whole Foods also puts several hundred dollars into a health savings account for each worker.This money can be used to cover routine medical expenses, like drug purchases or antismoking programs. If that money is not used in a year, the workers can save the money to pay for expenses in later years.

This type of plan does not excite proponents of a single-payer system, who think that individuals can't make wise health-care choices, and that this type of system is "antiwellness" because it discourages spending on preventive care.

Mr. Mackey scoffs at that idea: "The assumption behind that is that people don't care about their own health, and that somebody else has to—a nanny or somebody—has to take care of me because people are too stupid to make these decisions themselves. That's not been our experience. We find our team members [employees], not surprisingly, seem to care a whole lot about their health."

Not surprisingly, Mr. Mackey is a fanatic about healthy eating. "A healthy diet is a solution to many of our health-care problems. It's the most important solution. How much sugar do you think Americans consume?" he asks. I shrug and he rattles off the statistics: "Every man, woman and child consumes, on average, 43 teaspoons of sugar a day. In 13 days that adds up to a five-pound bag of sugar."

"We can spend all the money we want on bypass surgeries, chemotherapy and diabetes, but . . . two-thirds [of Americans] are overweight, one-third are obese." He's on a roll: "And it's not that they have to shop at a Whole Foods Market. But people need to eat whole food plant foods, primarily . . . whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds. That diet supports our lives. We ought to live to be 90 or 100 without getting any diseases."

Healthy eating, curbing the obesity epidemic—it's hard to find much of anything Mr. Mackey says that's controversial. But the health-care reform lobby continues to attack Whole Foods as if he were an apostate.

In response to the hullabaloo, Mr. Mackey has been understandably defensive. In early September, he wrote about the op-ed on his blog: "I gave my personal opinions. Whole Foods has no official position on the issue." So I ask him, does he regret writing the article? "I regret the controversy that it caused for Whole Foods, but I don't regret writing it, because I think what I said is true and it needed to be said. I wasn't seeing anyone else saying it."

Then he adds, half-jokingly: "I've written one op-ed piece in 31 years. It might be 31 more before I write another one."

I ask if he thinks the attacks were instigated by unions. While many other grocery chains are unionized, Whole Foods is not. "Well, the unions have had an adversarial relationship with us," he replies. "I don't think all the protests are strictly union-based, but I do think the unions have contributed to that. I think they've piled on and in some cases are orchestrating some of it." He says he can't divulge private information about whether the boycott hurt sales, but the stock hasn't taken any hit.

"I sometimes think that unions don't understand that we live in a free society and people have the right to not select union representation if they don't want it. I oftentimes hear things like 'Whole Foods is preventing people from unionizing,' which is a lie. That's illegal. We can't prevent anyone from unionizing," Mr. Mackey says.

So why aren't they choosing it? "Because it's not in their best interest," he insists. "We have better benefits and higher pay" than Whole Foods' unionized competitors. "We wish the unions would respect people's right to not have a union." Do they keep agitating? "Yeah, they do."

John Mackey is unlike any other Fortune 500 CEO I have met. He's got ruffled, curly hair, is thin and amazingly fit. He recently completed a three-week hike on the Appalachian Trail. He dresses casually, and his demeanor is almost always laid back. But his close friends say, don't let that fool you. Mr. Mackey is fiercely competitive and hates to lose—two traits that help a lot in business.

His odyssey from a long-haired counterculture anticapitalist in the early 1970s to running a company that now has $8 billion in sales and 280 stores—is a remarkable tale in itself. He attended the University of Texas where he studied philosophy and religion. "I never got my college degree," he admits proudly.

He started Whole Foods in 1978 with one store in Austin with $45,000 of seed capital raised from families and friends. "We lost half of it in the first year and then made $5,000 the next year." He wanted to double down and asked the board to put up more money to expand and build bigger stores. "And of course they thought I was nuts. 'You lost half of our money in the first year.'"

The fledgling CEO convinced them that "if we don't grow, we probably won't survive." The first major super store in 1980 was a success "almost by 3 o'clock on the day it opened." It's been an upward trajectory of profits and sales ever since.

"Before I started my business, my political philosophy was that business is evil and government is good. I think I just breathed it in with the culture. Businesses, they're selfish because they're trying to make money."

At age 25, John Mackey was mugged by reality. "Once you start meeting a payroll you have a little different attitude about those things." This insight explains why he thinks it's a shame that so few elected officials have ever run a business. "Most are lawyers," he says, which is why Washington treats companies like cash dispensers.

Mr. Mackey's latest crusade involves traveling to college campuses across the country, trying to persuade young people that business, profits and capitalism aren't forces of evil. He calls his concept "conscious capitalism."

What is that? "It means that business has the potential to have a deeper purpose. I mean, Whole Foods has a deeper purpose," he says, now sounding very much like a philosopher. "Most of the companies I most admire in the world I think have a deeper purpose." He continues, "I've met a lot of successful entrepreneurs. They all started their businesses not to maximize shareholder value or money but because they were pursuing a dream."

Mr. Mackey tells me he is trying to save capitalism: "I think that business has a noble purpose. It's not that there's anything wrong with making money. It's one of the important things that business contributes to society. But it's not the sole reason that businesses exist."

What does he mean by a "noble purpose"? "It means that just like every other profession, business serves society. They produce goods and services that make people's lives better. Doctors heal the sick. Teachers educate people. Architects design buildings. Lawyers promote justice. Whole Foods puts food on people's tables and we improve people's health."

Then he adds: "And we provide jobs. And we provide capital through profits that spur improvements in the world. And we're good citizens in our communities, and we take our citizenship very seriously at Whole Foods."

I ask Mr. Mackey why he doesn't collect a paycheck. "I'm an owner. I have the exact same motivation any shareholder would have in the Whole Foods Market because I'm not drawing a salary from the company. How much money does anybody need?" More to the point, he says, "If the business prospers, I prosper. If the business struggles, I struggle. It's good for morale." He hastens to add that "I'm not saying anybody else should do what I do."

Well, that's not exactly true. Mr. Mackey has been vocal in his opposition to recent CEO salaries. "I do think that it's the responsibility of the leadership of an organization to constrain itself for the good of the organization. If you look at the history of business in America, CEOs used to have much more constraint in compensation and it's gone up tremendously in the last 30 years."

He bemoans the trend that once a Fortune 500 CEO made about 25 times the average worker pay, and now that's climbed to 300 times average employee pay. He says this violates the principle of "internal equity—what your leadership is getting paid relative to everyone else in the organization."

But there's one other institution John Mackey thinks needs a makeover—and that's government. He describes what the Federal Reserve has done with massive money creation as "debauchery of the currency." He thinks the bailouts were a travesty.

"I don't think anybody's too big to fail," he says. "If a business fails, what happens is, there are still assets, and those assets get reorganized. Either new management comes in or it's sold off to another business or it's bid on and the good assets are retained and the bad assets are eliminated. I believe in the dynamic creativity of capitalism, and it's self-correcting, if you just allow it to self-correct."

That's something Washington won't let happen these days, which helps explain why Mr. Mackey felt compelled to write that the Whole Foods health-insurance program is smarter and cheaper than the latest government proposals. As he races out the door to catch a flight to spread the gospel of conscious capitalism elsewhere, I only hope he gets an aisle seat. He deserves it.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

A Four-Step Health-Care Solution

It's true that the U.S. health care system is a mess, but this demonstrates not market but government failure. To cure the problem requires not different or more government regulations and bureaucracies, as self-serving politicians want us to believe, but the elimination of all existing government controls.

It's time to get serious about health care reform. Tax credits, vouchers, and privatization will go a long way toward decentralizing the system and removmg unnecessary burdens from business. But four additional steps must also be taken:

1. Eliminate all licensing requirements for medical schools, hospitals, pharmacies, and medical doctors and other health care personnel. Their supply would almost instantly increase, prices would fall, and a greater variety of health care services would appear on the market.

Competing voluntary accreditation agencies would take the place of compulsory government licensing--if health care providers believe that such accreditation would enhance their own reputation, and that their consumers care about reputation, and are willing to pay for it.

Because consumers would no longer be duped into believing that there is such a thing as a "national standard" of health care, they will increase their search costs and make more discriminating health care choices.

2. Eliminate all government restrictions on the production and sale of pharmaceutical products and medical devices. This means no more Food and Drug Administration, which presently hinders innovation and increases costs.

Costs and prices would fall, and a wider variety of better products would reach the market sooner. The market would force consumers to act in accordance with their own--rather than the government's--risk assessment. And competing drug and device manufacturers and sellers, to safeguard against product liability suits as much as to attract customers, would provide increasingly better product descriptions and guarantees.

3. Deregulate the health insurance industry. Private enterprise can offer insurance against events over whose outcome the insured possesses no control. One cannot insure oneself against suicide or bankruptcy, for example, because it is in one's own hands to bring these events about.

Because a person's health, or lack of it, lies increasingly within his own control, many, if not most health risks, are actually uninsurable. "Insurance" against risks whose likelihood an individual can systematically influence falls within that person's own responsibility.

All insurance, moreover, involves the pooling of individual risks. It implies that insurers pay more to some and less to others. But no one knows in advance, and with certainty, who the "winners" and "losers" will be. "Winners" and "losers" are distributed randomly, and the resulting income redistribution is unsystematic. If "winners" or "losers" could be systematically predicted, "losers" would not want to pool their risk with "winners," but with other "losers," because this would lower their insurance costs. I would not want to pool my personal accident risks with those of professional football players, for instance, but exclusively with those of people in circumstances similar to my own, at lower costs.

Because of legal restrictions on the health insurers' right of refusal--to exclude any individual risk as uninsurable--the present health-insurance system is only partly concerned with insurance. The industry cannot discriminate freely among different groups' risks.

As a result, health insurers cover a multitude of uninnsurable risks, alongside, and pooled with, genuine insurance risks. They do not discriminate among various groups of people which pose significantly different insurance risks. The industry thus runs a system of income redistribution--benefiting irresponsible actors and high-risk groups at the expense of responsible individuals and low risk groups. Accordingly the industry's prices are high and ballooning.

To deregulate the industry means to restore it to unrestricted freedom of contract: to allow a health insurer to offer any contract whatsoever, to include or exclude any risk, and to discriminate among any groups of individuals. Uninsurable risks would lose coverage, the variety of insurance policies for the remaining coverage would increase, and price differentials would reflect genuine insurance risks. On average, prices would drastically fall. And the reform would restore individual responsibility in health care.

4. Eliminate all subsidies to the sick or unhealthy. Subsidies create more of whatever is being subsidized. Subsidies for the ill and diseased breed illness and disease, and promote carelessness, indigence, and dependency. If we eliminate them, we would strengthen the will to live healthy lives and to work for a living. In the first instance, that means abolishing Medicare and Medicaid.

Only these four steps, although drastic, will restore a fully free market in medical provision. Until they are adopted, the industry will have serious problems, and so will we, its consumers.

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

The Competition Cure

A better idea to make health insurance affordable everywhere.

(http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203550604574360923109310680.html)"Competition" has become a watchword of Team Obama's push for its health-care bill. Specifically, the Administration has defended its public insurance option as a necessary competitive goad to the private health insurance industry.

Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius routinely calls for more choice and competition in health care. In his weekly address this past weekend, President Obama raised the issue directly: "The source of a lot of these fears about government-run health care is confusion over what's called the public option. This is one idea among many to provide more competition and choice, especially in the many places around the country where just one insurer thoroughly dominates the marketplace." We take it this refers to a state in which one insurer holds most of the business.

It is no secret that this page is all for competition in the marketplace. If indeed that's the goal, allow us to suggest a path to it that will be a lot easier than erecting the impossible dream of a public option: Let insurance companies sell health-care policies across state lines.

This excellent idea has been before Congress since at least 2005, when Rep. John Shadegg of Arizona proposed it. It came up again recently in an exchange between Chris Wallace of Fox News Sunday and John Rother, executive vice president of AARP.

Mr. Wallace: "If you really want competition why not remove the restriction which now says that if I live in Washington, D.C. I've got to buy a D.C. health plan, and instead create a national market for health insurance, so that if there's a cheaper plan in Pennsylvania, I could buy in Pennsylvania?"

Mr. Rother: "There are states and localities where health care is much less expensive than others, and if we allow people to buy all their insurance from those places, it will raise the rates there. And it's called risk selection. It's a real problem, given the fact that health care costs can vary substantially from one place to another. So I think while the idea sounds appealing, the consequence would be it would make health care more expensive for those people who live in those low-cost areas."

How did Mr. Rother arrive at this conclusion?

His claim assumes that what makes insurance expensive in places like New Jersey—where the annual cost of an individual plan for a 25-year-old male in 2006 was $5,880—is merely the higher cost of medical services in the Garden State. He sounds an alarm in the rest of the country by suggesting that an individual living in, say, Kentucky—where an annual plan for a 25-year-old male cost less than $1,000 in 2006—would be asked to subsidize plan members living in high-priced states.

That's not how interstate insurance would work. Devon Herrick, a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis who has written extensively on this subject, notes that insurance companies operating nationally would compete nationally. The reason a Kentucky plan written for an individual from New Jersey would save the New Jerseyan money is that New Jersey is highly regulated, with costly mandated benefits and guaranteed access to insurance.

Affordability would improve if consumers could escape states where each policy is loaded with mandates. "If consumers do not want expensive 'Cadillac' health plans that pay for acupuncture, fertility treatments or hairpieces, they could buy from insurers in a state that does not mandate such benefits," Mr. Herrick has written.

A 2008 publication "Consumer Response to a National Marketplace in Individual Insurance," (Parente et al., University of Minnesota) estimated that if individuals in New Jersey could buy health insurance in a national market, 49% more New Jerseyans in the individual and small-group market would have coverage. Competition among states would produce a more rational regulatory environment in all states.

This doesn't mean sick people who have kept up their coverage but are more difficult to insure would be left out. Congressman Shadegg advocates government funding for high-risk pools, noting that their numbers are tiny. The big benefit would come from a market supply of affordable insurance.

Mr. Rother also said "risk selection" is a problem. But the coverage mandates cause that. As more healthy people opt out of health insurance because it is too expensive relative to what they consume, the pool transforms into a group of older, sicker people. Prices go higher still and more healthy people flee. High-mandate states are in what experts call an "adverse selection death spiral."

Interstate competition made the U.S. one of the world's most efficient, consumer driven markets. But health insurance is a glaring exception. When the competition caucus in Team Obama has to look for Plan B, this is it.

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

A Green Thumb on an Invisible Hand: Can Markets Improve the Environment?

Many think of the market as a mighty, erratic beast capable of transporting continents upon its back when domesticated by the adroit hands of statesmen but if left untamed would raze the defenseless into microscopic particles. This conception of networks of voluntary exchange is a dire mistake on a host of issues none more considerable than the environment. Too much trust is yielded to regulation and oversight while industries holding much ecological promise such as Solid Waste Disposal, Agribusiness and Nuclear Power fall victim to misinformed zealots who end up undermining their cause.The last place one expects to discover eco-centered innovation are smelly eyesores yet within the past thirty years dumps have handily outpaced expectations. Because these rolling hills of refuse are such easy targets a piece of legislation entitled the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) was passed by Congress in 1976 regulating waste materials. Later tighter restrictions on landfills were added through Subtitle D in 1991. After the passage of Subtitle D a measurable decline in Solid Waste Management facilities lead to more privatization and larger sites. By conventional wisdom this paradigm shift should have resulted in catastrophe. What actually occurred was remarkable.

Despite a steady flow of solid waste, landfill capacity actually increased with time. Between 1986-1991 13 states reported their dumps contained under 5 years of capacity. Presently, no states report landfills below 5 years of capacity, and the numbers for national facilities are even more heartening. These sites retained 11 years of capacity in the late-'80s, jumped to 14 years through the mid-'90s and currently maintain around 16 years of capacity. (source) Considering the rate of waste in the U.S. remains relatively constant per capita but swells in relation to population, these statistics become quite astounding. Even though more garbage enter landfills the lifespan of these sites increases. Incineration, improved recycling rates and inter-state capacity sharing assist in controlling landfill volume nationwide. (source)

Even the deleterious consequences of dumps have either been tapered or commuted. The strategic placement of landfills away from densely populated residential areas and waterways largely mitigates ground water contamination. Porous, subterranean fabrics called geotextiles filter hazardous pollutants inhibiting dangerous leakage. Methane gas emissions from decomposing trash can now be harnessed as an energy source. Carpet manufacturer, Interface Inc., decreased natural gas consumption by 20% since implementing this new technique in 2003. (source) Breakthroughs keep refining these technologies year after year ensuring improved safety and performance.Further up the chain of production Agribusiness continually boasts more efficient ways of cultivating crops with clever weather-resistant features. How any conscious, purportedly compassionate person could daunt this agricultural explosion falls beyond censure. The genetic strides engineered by private companies allow third world farmers greater growing flexibility and output, and the simple fact is because of these graciously unnatural modifications more food is generated globally with less land than ever before. Taking the numbers for the U.S. alone, corn harvests have increased by an additional 36%, soybeans by 12% and cotton by 31% thanks to biotechnology. (source) Farmers now use wireless equipment to measure how much water and fertilizer crops require to reduce waste and lower costs. Researchers augmented the plants themselves so they recover more quickly during droughts and floods -- an answered prayer to poor, Asiatic nations; require less tilling decreasing the overall amount of erosion and runoff; rely on 70% less water with equal or greater yields and repel pests diminishing the application of pesticides. Genetically modified seeds currently inaccessible to farmers are projected to be brought to market as soon as 2012.

Strictly "organic" farmers experience none of these benefits and leave behind a larger environmental footprint than Agribusiness. Because local farms deliver to a legion of individual retailers without a primary distribution center or encourage customers to pick-up their goods directly more fossil fuel gets dumped into the atmosphere while Agribusiness ships in bulk to fewer locations and imports their product from all over the world from regions specifically chosen to maximize efficiency for any given commodity. (source) The result is cheaper prices, better quality and less greenhouse gasses.As demonized as Agribusiness and genetically modified foods, or "Frankenfoods," are at present no other industry proves to be a scarier boogieman for nebbish environmentalists than Nuclear Power. Three Mile Island and Chernobyl cast long shadows over the legacy of this safe, clean wonder-fuel. To set the record straight, no one died at Three Mile Island and, although tragic, the 56 dead at Chernobyl is dwarfed by the countless dead due to ash coughed up by coal factories annually not to mention the human cost of resource wars launched in the name of oil. When the death tolls are placed side by side the hysteria orbiting Nuclear Power seems rather nitwitted.

Economically, Nuclear Power Plants make sense. They receive fewer subsidies than coal, oil, solar or wind power even though coal and oil are far bigger polluters, and by the most recent estimates solar and wind power at their peak could only satisfy 20% of demand while Nuclear Power could assure 90% of all energy needs. Nuclear power also outperforms the status quo. For instance, a single enriched uranium pellet equals "17,000 cubic feet of natural gas, 1,780 pounds of coal [and] 149 gallons of oil." (source) Despite a deficit in funding, Nuclear Plants cover the total cost of externalities and the decommissioning of outdated facilities. (source) No other clean power source produces more for less.

But can it be labeled clean or safe? When measuring the output of hazardous material nuclear power barely charts next to coal. The American coal industry unleashes more physical waste every few hours than Nuclear Power's entire history. This distressing quantity factors into the question of radioactivity. Not many people realize coal ash is radioactive although Uranium has greater intensity the disparity in the waste ratio between coal and nuclear power crowns coal ash the more worrisome environmental threat. Because of the diminutive amount of waste Nuclear Plants leave behind it can be altered into a watertight material, locked into steel-reinforced containers and buried well away from any underground water sources. (source)

As for the matter of safety, Chernobyl-style facilities have long since been decomissioned. In newer models, ceramic pellets encase pieces of uranium stored inside zirconium alloy tubes forming rods confined behind 30-centimeter thick walls which in turn are housed within a 1-meter thick barrier. During the burning process safety features slow efficiency if the water becomes too warm and several models of power plants depend upon physical forces such as gravity to halt the process altogether instead of mechanized components, and system redundancies double check the internal operations. (source) To further illustrate the safety of Nuclear Power Plants, during the Cold War neither the United States nor the Soviet Union aimed warheads at these complexes because the damage would have been negligible at best.

The collapse of Soviet Russia left an ecological moonscape as public proprietorship typically disintegrates into ruin. By contrast, thousands of largely private, collaborative hands shed elbow grease to manufacture sustainable technology inconceivable to any dark breed of central planner. The alacrity, plasticity and innovatory brawn behind markets can be overwhelming but this stupefying creature functions best when left unyoked.

Profit: Not Just a Motive

By Steven Horwitz

(http://www.thefreemanonline.org/featured/profit-not-just-a-motive/)

One of the more common complaints of critics of the market is that “the profit motive” works at cross-purposes with people and firms doing “the right thing.” For example, Michael Moore’s film Sicko was motivated by his desire to take the profit motive out of health care because, in his view, the ways people seek profits do not lead them to provide the level and kind of care he thinks patients should have.

Leaving aside for a moment whether the health-care industry is really dominated by the profit motive (given that almost half of U.S. health-care expenditures are paid for by the federal government, it is not clear which motives dominate) and whether Moore knows better than millions of individuals what their health-care needs are, the claim that a “motive” is a root cause of social pathologies is worthy of some critical reflection. The critics seem to suggest that if people and firms were motivated by something besides profit, they would be better able to provide the things that patients really need.

The overarching problem with blaming a “motive” is that it ignores the distinction between intentions and results. That is, it ignores the possibility of unintended consequences, both beneficial and harmful. Since Adam Smith, economists have understood that the self-interest of producers (of which the profit motive is just one example) can lead to social benefits. As Smith famously put it, it is not the “benevolence” of the baker, butcher, and brewer that leads them to provide us with our dinner but their “self-love.” Smith’s insight, which was a core idea of the broader Scottish Enlightenment of which he was a part, puts the focus on the consequences of human action, not their motivation.

What we care about is whether the goods get delivered, not the motives of those who provide them. Smith led economists to think about why it is that, or under what circumstances, self-interest leads to beneficial unintended consequences. It is perhaps human nature to assume that intentions equal results, or that self-interest means an absence of social benefit, as was often the case in the small, simple societies in which humanity evolved. However, in the more complex, anonymous world of what Hayek called “the Great Society,” the simple equation of intentions and results does not hold.

As Smith recognized, what determines whether the profit motive leads to good results are the institutions through which human action is mediated. Institutions, laws, and policies affect which activities are profitable and which are not. A good economic system is one in which those institutions, laws, and policies are such that the self-interested behavior of producers leads to socially beneficial outcomes. In mixed economies like that of the United States, the institutional framework often rewards profit-seeking behavior that does not produce social benefit or, conversely, prevents profit-seeking behavior that could produce such benefits. For example, if agricultural policy pays farmers not to grow, then the profit motive will lead to lower food supplies. If environmental policy confiscates land with endangered species on it, owners of such land who are driven by the profit motive will “shoot, shovel, and shut up” (that is, kill off and bury any endangered species they find on their land).

The same issues can be raised in the health-care industry. Before blaming the profit motive for the problems in the industry, critics might want to look at the ways in which existing government programs like Medicare and Medicaid, the interpretation of tort laws, and regulations such as those that limit who can practice what sorts of medicine might lead firms and professionals to engage in behavior that is profitable but unbeneficial to consumers. Labeling the profit motive as the source of the problem enables the critics to ignore the really difficult questions about how institutions, policies, and laws affect the profit-seeking incentives of producers and how that profit-seeking behavior translates into outcomes. Placing the blame on the profit motive without qualification simply overlooks the Smithian question of whether better institutions would enable the profit motive to generate better results and whether current policies or regulations are the source of the problem because they guide the profit motive in ways that produce the very problems the critics identify.

For example, high medical costs may well be a result of profit-seeking providers’ recognizing that government programs are notoriously bad at pricing services accurately and keeping good track of their expenditures. Ignoring the way institutions might affect what is profitable is often due to a more general blind spot about the possibility of self-interested behavior generating unintended beneficial consequences. Before we attempt to banish the profit motive, shouldn’t we see whether we can make it work better?

Placing blame for social problems on the profit motive is also easy if critics offer no alternative. What should be the basis for determining how resources are allocated if not in terms of profit-seeking behavior under the right set of institutions? How should people be motivated if not by profit? Often this question is just ignored, as critics are merely interested in casting blame. When it is not ignored, the answers can vary, but they mostly invoke a significant role for government. The interesting aspect of such answers is that critics do not suggest that we somehow convince producers to act on the basis of something other than profit, but that instead we replace them with presumably other-motivated bureaucrats or have those bureaucrats severely limit the choices open to producers. The implicit assumption, of course, is that the government personnel will not be motivated by profits or self-interest in the same way as the private-sector producers are.

How realistic this assumption is remains highly questionable. Why should we assume that government officials are any less self-interested than private individuals, especially when the door between the two sectors is constantly revolving? And if government officials do act in their self-interest and are motivated by the political analogs of profits (for example, votes, power, budgets), will they produce results that are any better than the private sector’s? If blaming the profit motive entails giving government a bigger role in solving problems, what assurance can critics of the profit motive provide that political officials will be any less self-interested and that their self-interest will produce any better results?

One will look in vain in Sicko, for example, for any analysis of the failures of state-sponsored health care in Cuba, Canada, Great Britain, or anywhere else. To blame the profit motive without asking whether an alternative will better solve the problems supposedly caused by the profit motive is to bias the case against the private sector.

How Will They Know?

Even this argument, however, does not go far enough. We are still, after all, focused on intentions and motivation. What critics of the profit motive almost never ask is how, in the absence of prices, profits, and other market institutions, producers will be able to know what to produce and how to produce it. The profit motive is a crucial part of a broader system that enables producers and consumers to share knowledge in ways that other systems do not.

Suppose for a moment that we try to take the profit motive out of health care by going to a system in which government pays for and/or directly provides the services. Suppose further that we could, somehow, ensure that the political officials would not be self-interested. For many critics of the profit motive, the problem is solved because public-spirited politicians and bureaucrats have replaced profit-seeking firms.

Well, not so fast. By what method exactly will the officials know how to allocate resources? By what method will they know how much of what kind of health care people want? And more important, by what method will they know how to produce that health care without wasting resources? It’s one thing to say that every adult should, for example, have a checkup every year, but should it be provided by an MD, an LPN, or an RN? What kind of equipment should be used? How thorough should it be? And most crucially, how will political decision-makers know if they’ve answered these questions correctly?

In markets with good institutions, profit-seeking producers can get answers to these questions by observing prices and their own profits and losses in order to determine which uses of resources are more or less valuable to consumers. Rather than having one solution imposed on all producers, based on the best guesses of political officials, an industry populated by profit seekers can try out alternative solutions and learn which ones work most effectively. Competition for profit is a process of learning and discovery. For all the profit-critics’ concern—especially but not only in health care—that allocating resources by profits leads to waste, few if any understand how profits and prices signal the efficiency (or lack thereof) of resource use and allow producers to learn from those signals. The most profound waste of resources in the U.S. health-care industry stems from the incentives and market distortions created by government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.

Thus the real problem with focusing on the profit motive is that it assumes that the primary role of profits is to motivate (or in contemporary language “incentivize”) producers. If one takes that view, it might seem relatively easy to find other ways to motivate them or to design a new system where production is taken over by the state. However, if the more important role of profits is to communicate knowledge about the efficiency of resource use and enable producers to learn what they are doing well or poorly, the argument becomes much more complicated. Now the critics must explain what in the absence of profits will tell producers what they should and should not do. Eliminating profit-seeking from an industry doesn’t just require that a new incentive be found but that a new way of learning be developed as well. Profit is not just a motive; it is also integral to the irreplaceable social learning process of the market. Critics may consider eliminating the profit motive the equivalent of giving the Tin Man from Oz a heart; in fact it’s much more like Oedipus’ gouging out his own eyes.

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Free Market Science vs. The Free Rider Problem

by Ryan Faulk

(http://fringeelements.ning.com/profiles/blogs/free-market-science-vs-the)

The free rider problem as it pertains to scientific research is as follows:

Company A spends $100K on developing a product, but company B can spend $10K and copy it, having the exact same product. Thus research and development is punished on a free market. That's the theory.

Edwin Mansfield, the late economist at the University of Pennsylvania came to the conclusion that in OECD countries, across all industry it costs $65 dollars to copy $100 worth of research. Or 65%. But that's just direct cost.

In order for a company to copy research, a great example is the drug industry, they have to have smart people. If I gave you a viagra pill, would you be able to reverse engineer that? No, a company needs to have smart people who can do that, with the equipment, on hand if they want to copy. So there are sunk costs involved if a company wants to copy research. This isn't just copying your neighbor's scantron answers.

Also it takes time to reverse engineer a product, and in that window the company that made the original product enjoys a monopoly. The more complex the innovation, the more difficult it tends to be to reverse engineer, and the longer that company enjoys a monopoly.

Given the advantage of the temporary monopoly of the originator plus the sunk costs needed for copiers to be able to copy, copying research and doing original research tend to come out as equally profitable strategies. Private firms in OECD spent about 3% of the budget on research.

That said, all firms engaged in research both copy and do original research themselves. Because in order to copy, you must have smart people doing original research in that field, you've got to have guys in the know, and when one company makes a breakthrough, everyone else rushes to copy.

The reason copying a product and originating a product tend to be equally profitable is basic economics. Products are only released by firms if it's revolutionary enough to earn a profit that makes up for the cost of development. And in order to make a profit, it must be difficult enough to provide a period of monopoly for those costs to be recuperated.

Products which are only slightly revolutionary aren't as expensive to develop as products which are extremely revolutionary, but also tend to be easier to reverse engineer, resulting in a shorter monopoly period. If you're interested in more detail, I would recommend Terence Kealey's book.

When the state funds scientific research, there is crowding out. For every $1 spent on research, $1.25 less is spent on research in private firms according to Kealey. I have an idea why this might be: government jobs are more secure and have shorter hours than private jobs, and so a government job of $100K a year is worth more than a free-market job of $100K a year. Or more discretely, a government job of $100K a year is worth about as much as a private job of $125K a year. That's just my guess as to why government funding crowds out private funding at more than a 1 to 1 ratio.

Also, government funding often goes to military research, which can lead to innovations there's no denying that, but it is not connected to what individuals choose to buy with their own money but what the military wants. And what the military wants isn't always tied to what's the best for waging war - for example the air force continues to fund the research of piloted aircraft because that provides jobs for pilots, whereas UAVs are clearly the wave of the future. The limiting factor of the F-22 wasn't the airframe, it was how many g's the pilot could take.

Francis Bacon, a torturer and an embezzler, in 1605 put forward the idea that science is a public good based on pure research. That yes it is applied science that leads to immediate discoveries, but that applied science can only come from a pure research background, which the short-sighted marketplace will not provide to appropriate degrees, and thus the state must fund pure research.

Now as it turns out, the best way for a firm to come up with some profitable breakthrough is to engage in pure research, because science is unpredictable and that which deals with the most fundamental and open-ended concepts - pure research, tends to result in the most novelty and thus breakthroughs.

And even companies whose sole goal is to merely keep up with the bigger companies and sell knock-offs of popular drugs have to employ scientists, and those scientists have to stay in the loop doing pure research. And so everyone is engaging in pure research constantly.

Francis Bacon's idea of state-funded science was implemented in France but not in Britain. Britain didn't implement any state science program until World War 1, and the United States didn't do very much at all until 1940.

Now one can always come up with many anecdotes about government funding of things causing that thing to come about, a great example that statist hack Noam Chomsky likes to bring up is the internet. As though connecting computers over long distances was something only state research could come up with. Sure, private research invents the airplane, automobile, about half of the computer, but connecting those computers together is a job for the state.

And on the airplane, at the time of the wright brothers, the Smithsonian was attempting to fly a heavier-than air craft as well. They were beat to it by the wright brothers.

Now just imagine if the Smithsonian had won, we wouldn't hear the end of it. "Oh, without the munificent foresight of state research planners, how would we have ever achieved heavier than air flight!" And the statists would make up arguments about the free market being unwilling to take such abstract risks or not being able to crash expensive airplanes repeatedly, and may even point and laugh at the wright brothers and say "look, there's your free market, two wacko brothers. Look at this clown show. What a failure! Maybe this crapshoot worked in 1000 AD, but look at how complex this things are now. Sure the free market worked then, but so did hunting with spears with spears. We're evolved, it's civilization. Enjoy your airplane, courtesy of the US government. Free market fundamentalist, you got pwned."

Anecdote. The state is not necessary to fund research and development, and from every angle of analysis, the state appears to pervert and distort the structure of production, in this case the production of scientific research.

How Interest Works

Even something as maligned as interest is an important part of a Free Market that, when not abused, can help you in the long run.

If Mexicans and Americans Could Cross the Border Freely

A meticulous and practical decimation of all the reasons typically given for why immigration should stay illegal. The authors then supply their own radical solution -- a completely open southern border. Agree? Disagree? Read more: http://www.independent.org/pdf/tir/tir_14_01_6_delacroix.pdf

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

Neighbours hire their own police force

(http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1204819/Neighbours-hire-police-force-3-week.html)

There is always a price to pay for rising crime rates and an over-stretched police force.

But rarely is it so clear what that cost is. Residents of an affluent suburb in Southampton have decided to pay £3.15 a week to fund a private security force to patrol the streets.

Hundreds of residents who have 'lost faith in the police force' have clubbed together to hire the private team of uniformed officers to protect them from crime in the area.

At your service: Atraks owner Dave MacLean (right) with colleague Marvin Olszewski, as they patrol the streets of Southampton. They were hired privately by residents in fear of crime

Security firm Atraks says its team will use the powers of citizen arrest as they patrol the leafy streets of Upper Shirley to 'prevent serious crime' and 'neutralise' threats.

Eight uniformed officers equipped with handcuffs and stab vests will even escort homeowners to and from the bank or on shopping trips to ensure they are not mugged.

So far 337 people have signed up in the neighbourhood while a further 1,700 have said they will join once they see the service in action.

The Atraks service - which is being tried out for free - costs £3.15 a week or residents can make an annual, one-off payment of £163.80.

Atraks needs 500 people to sign up to the scheme within a three-square-mile area for it to go ahead full time.

It is claimed all residents within this area would benefit from the scheme - not just those who had contributed to the cost.

Upper Shirley is one of the most affluent parts of Southampton but is close to a number of run-down areas.

On the beat: MacLean with fellow officer Keith Harding. Critics say the private security force scheme simply fuels fear of crime

One resident, Paul Graham, said he has agreed to pay for the scheme because he thinks the Atraks officers will prevent crime, rather than just respond to it.

The 28-year-old van driver said: 'It's not a lot of money to pay for having peace of mind. If someone is patrolling the streets at night then it's definitely going to stop some crime from taking place.

'We do see the police now and again around here but they are always busy with other things and don't have time to drive down every street.

'They will come if you call them but I think the Atraks scheme will be much more preventative.'

Another resident, an elderly woman who wished to remain anonymous, said: 'It is ludicrous that we pay our taxes and then have to pay again for a decent level of protection but I don't see any other option.'

Despite the widespread support, the scheme has come under fire from critics who say it will exaggerate the fear of violence.

But Dave MacLean, who launched Atraks two years ago, said he was acting after canvassing the opinions of local residents.

The 26-year-old former dog handler said: 'Most said they were fed up with the level of protection offered by the police and had lost faith. The police should be here to protect us and a company like ours shouldn't really be needed.'

Atraks officers will not have any powers other than those afforded to all citizens.

But Mr MacLean said his team of eight officers will talk to residents and be a visible presence on the streets to deter criminals.

They will also patrol outside schools, provide escorts to shops and banks, respond to alarms and help disperse street gangs. The service will involve dedicated patrols of officers trained in 'handcuffing, crime scene preservation, statement taking and firefighting'.

But local Labour MP Alan Whitehead criticised the scheme, saying it was 'based on exaggerating both a fear of crime and their own legal and practical powers in responding to concerns'.

He added: 'I remain of the view that a paid vigilante service is not the best way to ensure that our communities are kept safe.'

Saturday, August 08, 2009

The Market Doesn’t Ration Health Care

By Sheldon Richman

(http://fee.org/articles/tgif/markets-ration-health-care/)

Healthcare reformers say they have two objectives: to enable the uninsured and under-insured to consume more medical services than they consume now, and to keep the prices of those services from rising, as they have been, faster than the prices of other goods and services. Unfortunately, Economics 101 tells us that to accomplish those two things directly — increased consumption by one group and lower prices — the government would have to take a third step: rationing. The reformers are disingenuous about this last step, and for good reason. People don’t like rationing, especially of medical care.

But some defenders of government control acknowledge that rationing is the logical consequence of their ambition. They parry objections by saying in effect: “So we’ll have to ration. Big deal. We already have rationing — by the market.”

For example, Uwe Reinhardt, an economics professor and advocate of government-controlled medicine, writes, “In short, free markets are not an alternative to rationing. They are just one particular form of rationing. Ever since the Fall from Grace, human beings have had to ration everything not available in unlimited quantities, and market forces do most of the rationing.”

Sadly, interventionist economists are not the only economists who talk this way. Most free-market economists would agree that where there is scarcity there must be rationing and that the most efficient way to ration is by price, that is, through the market.

This is factually wrong and strategically ill-advised. As we’ll see, markets do not ration. Thus the healthcare debate is not about which method of rationing — State or market — is superior.

Let me be clear about what I am not denying. I am not denying that economic goods are by definition scarce and that at any given time we must settle for less of them than we want. I am also not denying that the marketplace is relevant in determining who gets how much of those scarce goods.

I am denying that this is appropriately called “rationing.”

Markets Don’t Do Anything

To see that the market does not ration one need only see that “the market” doesn’t do anything. To talk as if it does things is to reify the market — worse, it is to anthropomorphize the market, ascribing to it attributes — purposes, plans, and actions — that only human beings possess. We may also see this as another instance of literalizing a metaphor, which, as Thomas Szasz has so often warned, is fraught with peril.

I’m not saying that economists don’t realize this diction is a metaphor. Of course they do, and there’s no harm in using this shorthand among those who understand it as such. The problem, as I see it, is that the general public doesn’t fully grasp the metaphorical nature of these statements. For the sake of public understanding, free-market advocates should not welcome a debate in which they begin by saying, “Our method of rationing is better than your method of rationing.”

Better to respond to the interventionists this way: The market does not ration or allocate. The market does not do anything. It has no purposes or objectives. It is simply a legal framework in which people do things with their justly acquired property and their time in order to pursue their own purposes.

This is squarely in the Austrian conception of the market as set out by Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek. The market order “has no specific purposes but will enhance for all the prospects of achieving their respective purposes,” Hayek wrote in volume two of Law Legislation, and Liberty.

The market was never set up by people to achieve a purpose. It is not a device or an invention aimed at satisfying an intention. “Market mechanism” is a metaphor. The market — as a set of continuing relations among people — emerged, unplanned and unintended, from exchanges, initially barter, in which the parties intended only to improve their respective situations. Lecturing at FEE this week, Israel Kirzner recalled that one of the first things Mises said to him as a graduate student was, “The market is a process,” by which he meant “a series of activities.” This is similar to what the French liberal economist Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836) wrote in A Treatise on Political Economy, “Society is purely and solely a continual series of exchanges.”

Mises, Hayek, and Tracy help us to sort out the rationing question. I submit it makes no sense to say that an undesigned series of exchanges rations goods. If we were to observe a free market (wouldn’t that be nice?), what would we see? Rationing? Allocation? Of course not. We would see people exchanging things — factors of production, services, and consumer goods — for money. Where would they have gotten those things? From previous exchanges or original appropriation from nature.

When a person buys five apples in a grocery store rather than ten because he wishes to use the rest of his money for other purposes, it seems entirely wrong to say the market (or even the grocer) has rationed the apples. The customer makes his choice on the basis of his preferences and the money available (which is the result of previous transactions).

It is true that as a result of market exchanges, goods and resources change hands and (except for land) locations. But in no sense is this rationing or allocation. The resulting arrangement of resources is simply a product of many transactions. Of course, people’s choices of what and what not to buy and sell at which prices create an arrangement of goods and resources that tends to be intelligible in terms of consumers’ subjective priorities. But that does not warrant calling the process rationing or allocation.

Those words — especially ration, which shares its root with rational – suggest conscious decision-making — as part of a plan — by an agent. In a free market there is no consciousness overseeing this “distribution” — another inappropriate word when it comes to describing the market process.

I am not saying anything that a good economist or thoughtful person doesn’t know. I am merely pointing out that we can be more effective in the healthcare debate if we are more precise in our language. We do not face a choice between methods of rationing medical services. We face a choice between rationing according to a bureaucratic plan and being freed to engage in mutually beneficial exchanges.

Sheldon Richman is the editor of The Freeman and "In brief." He is a contributor to The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

Thursday, July 30, 2009

Cutthroat Capitalism: An Economic Analysis of the Somali Pirate Business Model

(http://www.wired.com/politics/security/magazine/17-07/ff_somali_pirates)

The rough fishermen of the so-called Somali coast guard are unrepentant criminals, yes, but they're more than that. They're innovators. Where earlier sea bandits were satisfied to make off with a dinghy full of booty, pirates who prowl northeast Africa's Gulf of Aden hold captured ships for ransom. This strategy has been fabulously successful: The typical payoff today is 100 times what it was in 2005, and the number of attacks has skyrocketed.

Like any business, Somali piracy can be explained in purely economic terms. It flourishes by exploiting the incentives that drive international maritime trade. The other parties involved — shippers, insurers, private security contractors, and numerous national navies — stand to gain more (or at least lose less) by tolerating it than by putting up a serious fight. As for the pirates, their escalating demands are a method of price discovery, a way of gauging how much the market will bear.

The risk-and-reward calculations for the various players arise at key points of tension: at the outset of a shipment, when a vessel comes under attack, during ransom negotiations, and when a deal is struck. As long as national navies don't roll in with guns blazing, the region's peculiar economics ensure that most everyone gets a cut.

All of which makes daring rescues, like the liberation in April of the Maersk Alabama's captain, the exception rather than the rule. Such derring-do may become more frequent as public pressure builds to deep-six the brigands. However, the story of the Stolt Valor, captured on September 15, 2008, is more typical. Here's how it played out, along with the cold, hard numbers that have put the Somali pirate business model at the center of a growth industry.

The Hot Zone: Pirates Know That Plunder Pays

Most of Somalia's modern-day pirates are fishermen who traded nets for guns. They've learned that ransom is more profitable than robbery, and rather than squandering their loot, they reinvest in equipment and training. Today, no ship is safe within several hundred miles of the Somali coast.

Illustration: Siggi Eggertsson

An ordinary Somali earns about $600 a year, but even the lowliest freebooter can make nearly 17 times that — $10,000 — in a single hijacking. Never mind the risk; it's less dangerous than living in war-torn Mogadishu.

Sunday, July 26, 2009

What's so great about Agorism?

agora -

n. pl. ag·o·rae (-r

) or ag·o·ras

A place of congregation, especially an ancient Greek marketplace.

As any skinny, ink-spattered punk claiming to be an Anarchist will assert revolutionary violence is the only answer against the toxic tentacles of the state. Albert Einstein, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. were all woefully wrong. Only the heat from a molotov cocktail or a shattered Starbucks street front window can force Goliath to genuflect. But governments are serpents coiling and squeezing around those who struggle for breath with three heads ready to replace any one that's severed.

From a distance what's a more absurd sight than a handful of hooded vegans taking arms against the largest military power ever amassed. Time to lock away your Schwinns, Mr. & Ms. Anarchist, Lady Liberty is packing heat and she will end you faster than you can say "In God We Trust."

Unless, there's a better way...

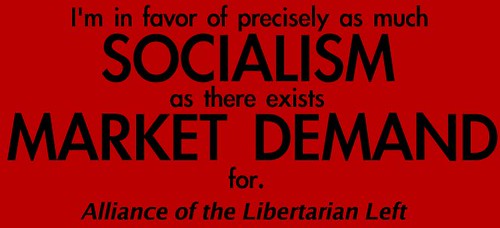

In the late '70s and early '80s a germ of an idea wafted through the subterranean corridors of Anarchist philosophy. What if there was a theory of social organization which involved markets that appealed to both the revolutionary left and the revolutionary right. Easier said than done. Right-Libertarians made attempts at reaching across the aisle to their left-wing brothers and sisters for years but alas their arms proved to be much too short. The man responsible for achieving great strides toward bridging this schism was Samuel Edward Konkin III also known as SEK3 on the streets. Konkin devised a concept of Anarchism which brought in the labor-centered, class-intensive focus of the left and married it with the Austrian economics of the right. He named it Agorism after the agora or marketplaces of Ancient Greece.

So, what's so great about Agorism? It recognizes that violence can't be met with violence. Of course by now it's just a cliche but aggression is cyclical. The best way to destroy a rotten idea (i.e. the state) is to replace it with a better one (i.e. voluntary exchange). Never a reformist, SEK3 decided the only logical form this revolution could take would be counter-economic meaning through black and gray markets, barter networks and local currencies. These counter-economies would naturally begin as tiny, grassroots cells then grow organically as they demonstrated they could deliver better quality goods and services cheaper without the burden of state mandated licensure and taxation. Think it's just a pipe dream? Well, think again. Counter-economies existed in the past in the Pacific Northwest in Canada with Indigenous Potlatch Festivals, and are being maintained in the present with Sustainable Communities some of which have their very own monetary system.

Agorism has also refurbished old chestnuts like Marx's and Engels' Class Theory. Everybody knows their views and its faults so they won't be rehashed here. From the ashheap of Marxism, Agorist Class Theory holds on to the two-class divide, yet, where the Communists get a little kookie is when they omit the state as a pestilential force. How odd, it seemed to be right there in front of their noses. The actual partition is between the politically connected and the economically productive. Robber Barons, Military Personnel and Politicians comprise the former while Entrepreneurs and Workers fill the latter. Of course, there are dynamic gradations between the classes all established by one's orientation to the bulbous, dangling teats of the state.

Beyond Agorism's appeal to pragmatism there is a sense of unity between all schools of Anarchist thought as one of its features. Since Anarchism's inception Anarchists haven't even been able to agree on how to change a light bulb let alone agree upon anything else. There are some hardliners on both sides who do readily dismiss this relatively new approach. Little do they realize the serpent cannot be decapitated. Only through non-participation will it eventually starve to death.

Thursday, July 16, 2009

Classical Liberalism and the Fight for Equal Rights

Remembering the forgotten libertarian legacy of American anti-racism

(http://www.reason.com/news/show/134651.html)

In a 1992 speech at Colorado's Metro State College, Columbia University historian Manning Marable praised the black minister and activist Malcolm X for pushing an "uncompromising program which was both antiracist and anticapitalist." As Marable favorably quoted from the former Nation of Islam leader: "You can't have racism without capitalism. If you find antiracists, usually they're socialists or their political philosophy is that of socialism."

Spend time on most college campuses and you're likely to hear something very similar. Progressives and leftists, the conventional narrative goes, fought the good fight while conservatives and libertarians either sat it out or sided with the bad guys. But there's a problem with this simplistic view: It completely ignores the fact that classical liberalism—which centers on individual rights, economic liberty, and limited government—played an indispensable role in the fight for equal rights.

Indeed, from the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who championed the natural rights philosophy of the Declaration of Independence and declared "give the negro fair play and let him alone," to the conservative newspaper magnate R.C. Hoiles (publisher of what is now the Orange County Register), who denounced liberal President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's wartime internment of Japanese Americans while most New Dealers (and liberal Supreme Court justices) remained silent, classical liberals have long opposed racism and collectivism in all of its vile forms.

This important yet sadly-neglected history is the subject of Race & Liberty in America (University Press of Kentucky), a superb new anthology edited by Southern Illinois University historian Jonathan Bean, which features carefully selected articles, speeches, book excerpts, newspaper accounts, legal decisions, interviews, and other materials revealing, in Bean's words, that "classical liberals are the invisible men and women of the long civil rights movement." (Full Disclosure: Bean includes one of my articles in a list of recommended readings.)

There's Lysander Spooner, the radical libertarian, legal theorist, and abolitionist who argued that slavery was illegal under both natural law and the U.S. Constitution; Louis Marshall, the "ultraconservative" NAACP attorney and lifelong Republican who won the Supreme Court case Nixon v. Herndon (1927), striking down the "white primaries" favored by racist Southern Democrats; and Zora Neale Hurston, the acclaimed Harlem Renaissance novelist and folklorist who denounced New Deal relief programs as "the biggest weapon ever placed in the hands of those who sought power and votes" and endorsed libertarian Sen. Robert A. Taft (R-Ohio) for president in 1952.