Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

That I cannot be a slave

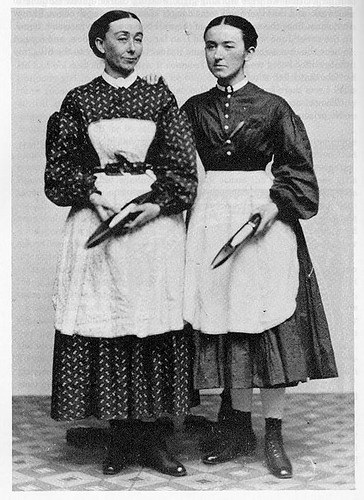

This was sung by the Lowell "Mill Girls" during their 1836 strike. Most worked for textile mills in order to send a single family member through school, usually a brother or son. Girls as young as ten were stuffed into sweltering rooms for up to 16 hours a day. Large, noisy machines spilled particles of fabric into the unventilated air, and the workers lived in factory-owned boardinghouses, paying their rent to the textile mill they labored under. When the factory raised the price of lodging the girls organized. They published literature bursting with poems and articles about their abhorrent working conditions, shared life stories and planned strikes. The first was in 1834 and ended messily. Some of the girls, after their defeat, were fired for agitating against the factory, the rest saw a reduction in wage. Instead of acquiescing the girls proved indefatigable. One of the girls delivered a brassy speech - the first time a woman spoke publicly in Lowell - on the humiliating treatment of the factory workers exciting the revolutionary spirit of much of the community and sickening the rest. But her ideas connected and two years after the first strike the mill girls won their battle against the factories and received better wages and shorter work days.

This was sung by the Lowell "Mill Girls" during their 1836 strike. Most worked for textile mills in order to send a single family member through school, usually a brother or son. Girls as young as ten were stuffed into sweltering rooms for up to 16 hours a day. Large, noisy machines spilled particles of fabric into the unventilated air, and the workers lived in factory-owned boardinghouses, paying their rent to the textile mill they labored under. When the factory raised the price of lodging the girls organized. They published literature bursting with poems and articles about their abhorrent working conditions, shared life stories and planned strikes. The first was in 1834 and ended messily. Some of the girls, after their defeat, were fired for agitating against the factory, the rest saw a reduction in wage. Instead of acquiescing the girls proved indefatigable. One of the girls delivered a brassy speech - the first time a woman spoke publicly in Lowell - on the humiliating treatment of the factory workers exciting the revolutionary spirit of much of the community and sickening the rest. But her ideas connected and two years after the first strike the mill girls won their battle against the factories and received better wages and shorter work days.The moral of the story is obvious: there is power in the union. It's really only a game of numbers. Today, the story of the Lowell "Mill Girls" seems like a half-remembered dream from a past life. We're taught the labor movement is antiquated, a cluster of old stories that have been rendered obsolete like the Old Testament. Nobody is educated in school on the Mill Girls or the Homestead Strike or the Flint Sit-Down Strike or about what pinkertons were or anything Woody Guthrie sang about. It is a crime of omission.

For some reason, girls just do it better, not only in the 19th century and not only in America. Women street vendors in India endured constant harassment from local police. Their produce would be confiscated then returned days later after it had spoiled. The vendors couldn't obtain health care or social security. A lack of child care limited their work day giving them a glaring disadvantage to male vendors and a lack of education prevented them from working elsewhere. The solution wasn't novel. It was the same government/corporate-bucking recipe that's worked for generations. The street vendors published their thoughts in newsletters, consolidated their trades under one, catch-all non-governmental organization. They fought local municipalities in court, struggled to gain access to social security and health care, and established daycare for their children.

For some reason, girls just do it better, not only in the 19th century and not only in America. Women street vendors in India endured constant harassment from local police. Their produce would be confiscated then returned days later after it had spoiled. The vendors couldn't obtain health care or social security. A lack of child care limited their work day giving them a glaring disadvantage to male vendors and a lack of education prevented them from working elsewhere. The solution wasn't novel. It was the same government/corporate-bucking recipe that's worked for generations. The street vendors published their thoughts in newsletters, consolidated their trades under one, catch-all non-governmental organization. They fought local municipalities in court, struggled to gain access to social security and health care, and established daycare for their children.In America, only 8% of workers are members of a trade union and thanks to the long-standing Taft-Hartley Act many of the incentives and protections granted to unions have been suspended. Plenty of restructuring is required in order to catch up to the women vendors of India or the Lowell "Mill Girls". First we need a vibrant labor press expressing working and middle class issues, perhaps best implemented through the internet, and second we can't divide ourselves by trade but unify all workers into a single federation.

Remember, the labor struggles of the past aren't irrelevant. No company out of the kindness of its heart ever gave their workers 8 hour work days or a livable wage as a gift, and no government was ever so generous as to grant its citizens more freedom than they demand. Corporations and governments are enemies of progress. Everything we enjoy today was won in battle after blood-spattered battle. But it is my sincerest hope that when the next great thrust forward comes the last thing our bloated plutocrats will hear is "Girl Power!"

1 comment:

Girl power indeed!

Always great reading Rich.

Post a Comment