What does the Bush administration really think about the military junta in Myanmar? Publicly, it condemns the government's actions but privately I suspect our handlers are moving us closer toward a military junta of our own. In Myanmar the internet is strictly monitored going as far as taking screen captures inside internet cafes every five minutes, the rulers live lavishly while the poor is largely ignored and a substantial portion of their income is devoted to a massive standing army. The parallels are frightening.

If this administration was serious about promoting Burmese democracy they wouldn't sanction the brutal regime. We've learned from Iraq that sanctions effect the people, not the government. We need to fund the pro-democracy resistance by providing proxy servers to help organize the counter-movement and by smuggling aid into the country.

SOURCE

Soldiers Hunt Dissidents in Myanmar

Soldiers Hunt Dissidents in MyanmarYANGON, Myanmar — Soldiers announced that they were hunting pro-democracy protesters in Myanmar’s largest city Wednesday and the top U.S. diplomat in the country said military police were pulling people out of their homes during the night.

Military vehicles patrolled the streets before dawn with loudspeakers blaring that: “We have photographs. We are going to make arrests!”

Shari Villarosa, the acting U.S. ambassador in Myanmar, said in a telephone interview that people in Yangon were terrified.

“From what we understand, military police … are traveling around the city in the middle of the night, going into homes and picking up people,” she said.

Residents living near the Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar’s most revered shrine and a flashpoint of unrest, reported that police swept through several dozen homes in the middle of the night, dragging away several men for questioning. The homes were located above shops at a marketplace that caters to the nearby pagoda, selling monks robes and begging bowls.

Meanwhile, the junta pursued other means of intimidation. An employee from the Ministry of Transport, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that he was told to sign a statement saying he and his family would not take part in any political activity and would not listen to foreign radio reports. Many in Myanmar use short-wave radios to pick up foreign English-language stations - a main source for news about their tightly controlled country.

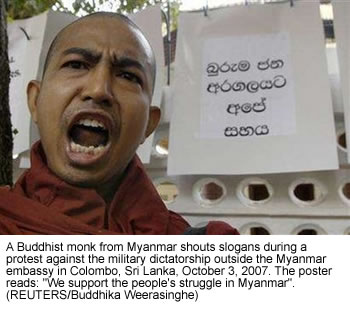

The U.N.’s special envoy, Ibrahim Gambari, declined to comment on his four-day mission to Myanmar, where the military junta last month crushed mass pro-democracy demonstrations led by the nation’s revered Buddhist monks.

Villarosa said embassy staff had gone to some monasteries in recent days and found them completely empty. Others were barricaded by the military and declared off-limits to outsiders.

“There is a significantly reduced number of monks on the streets. Where are the monks? What has happened to them?” she said. The Democratic Voice of Burma, a dissident radio station based in Norway, said authorities have released 90 of 400 monks detained in Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin state, during a midnight raid on monasteries on Sept. 25.

A semblance of normality returned to Yangon after daybreak, with some shops opening and light traffic on roads.

However, “people are terrified, and the underlying forces of discontent have not been addressed,” Villarosa said. “People have been unhappy for a long time … Since the events of last week, there’s now the unhappiness combined with anger, and fear.”

Some people remained hopeful that democracy would come.

“I don’t believe the protests have been totally crushed,” said Kin, a 29-year-old language teacher in Yangon, whose father and brother had joined a 1988 pro-democracy movement that ended in a crackdown in which at least 3,000 people were killed.

“There is hope, but we fear to hope,” she said. “We still dream of rearing our children in a country where everybody would have equal chances at opportunities.”

The military has ruled Myanmar since 1962, and the current junta came to power after snuffing out the 1988 pro-democracy movement. The generals called elections in 1990 but refused to give up power when Suu Kyi’s party won.

The military crushed the protests on Sept. 26 and 27 with live ammunition, tear gas and beatings. Hundreds of monks and civilians were carted off to detention camps. The government says 10 people were killed in the violence. But dissident groups put the death toll at up to 200 and say 6,000 people were detained.

Among those killed was Japanese television cameraman Kenji Nagai of the APF news agency. His body was flown from Myanmar to Tokyo on Wednesday.

Gambari went to Myanmar on Saturday to convey the international community’s outrage at the junta’s actions. He also hoped to persuade the junta to take the people’s aspirations seriously.

He met junta leader Senior Gen. Than Shwe and his deputies and talked to detained pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi twice.

Gambari avoided the media in Singapore, where he arrived Tuesday night en route to New York. He was not expected to issue any statement before briefing U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on Friday.

The junta has not commented on Gambari’s visit and the United Nations has only released photos of Gambari and a somber, haggard-looking Suu Kyi - who has spent nearly 12 of the last 18 years under house arrest - shaking hands during their meeting in a state guest house in Yangon.

In Singapore, Gambari met with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, the chairman of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations bloc of which Myanmar is a member.

A Singapore government statement said Lee told Gambari that ASEAN “is fully behind his mission” to bring about “a political solution for national reconciliation and a peaceful transition to democracy.”

© 2007 The Associated Press

No comments:

Post a Comment